When Howard treated Vance’s book, Hillbilly Elegy, it seemed somewhat natural given his background. Before taking on Hillbilly Elegy Howard had been involved in over 100 films including A Beautiful Mind and Cinderella Man which were together nominated for 11 Academy Awards. Howard had also treated much of the material before, most notably as a young actor in the role of Opie in The Andy Griffith Show, a hillbilly themed sitcom produced in the early 1960s.

There was also strong interest for such a film. Vance’s book had been on the New York Times bestseller list for over twenty weeks. When Trump’s election confounded media predictions, Hillbilly Elegy appeared to offer an answer as to why. As one reviewer put it, Hillbilly Elegy “struck a chord with a nation grappling with profound struggles of identity and poverty.” The New York Times’ Jennifer Senior remarked, “Mr. Vance has inadvertently provided a civilized reference guide for an uncivilized election.”

These initial readings of Vance’s book and Howard’s film have given way to institutional patterns that lay behind them. With JD’s shifting stance on Trump, his “elegy” appears less a personal statement than a calculated appeal, one that serves vested interests. In turn Howard’s extensive career in the film and television industry shines a light on the historical use of hillbilly culture in poplar media. One that extends beyond Vance’s text through Howard’s childhood role as Opie, finding its extension in the origins of cinema.

To explore these themes its instructive to look at the history of American eugenics. Largely unknown is that popular hillbilly culture has a shared history with that of the American eugenics movement. Since the earliest days of cinema, the hillbilly has been used to promote an entrenched stereotype that once was the foundational narrative of American eugenics. At a time when the terms “defective,” “feebleminded,” and “imbecile” were used by doctors and social workers as medical terms, eugenics was a method of surveillance legitimized by science that was used to categorize, institutionalize, and sterilize the poor.

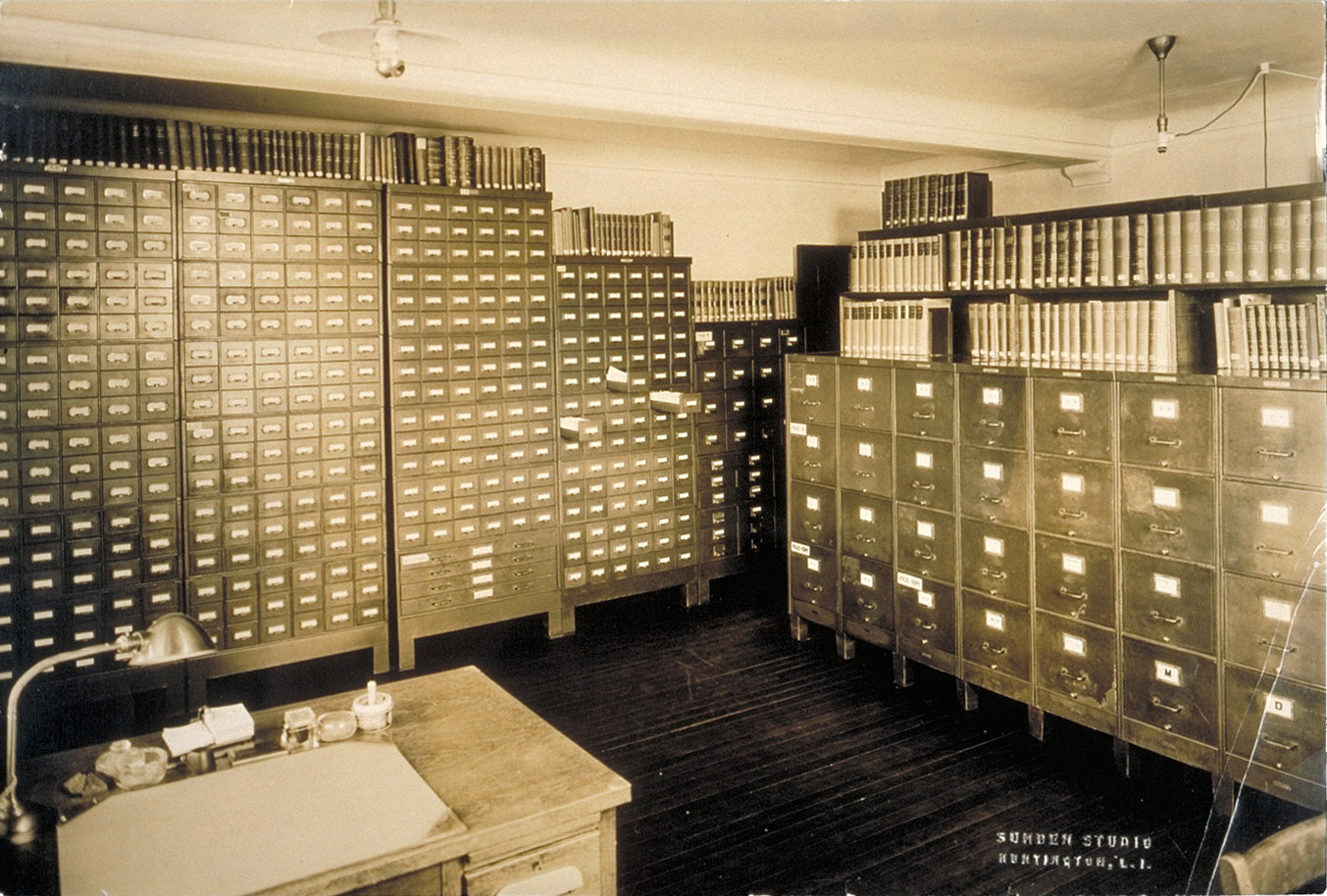

The Eugenics Record Office (ERO) in Cold Spring Harbor New York, produced the bulk of this surveillance. Set up in 1904 by Charles Davenport, the ERO sent out teams of researchers armed with eugenic questionnaires, to document “the great strains of human protoplasm…coursing through the country.”1 With funding from the Carnegie Institution, Rockefeller Fund, and Mrs. Harriman, the ERO’s research activities had a large impact on public policy leading to increased public funding for the institutionalization and sterilization of what were largely the poor.2 After eugenics was legalized by the Supreme Court’s 1927 Buck v. Bell decision, eugenic laws were enacted across the country, nearly tripling the number of forced sterilizations during the 1930s.3

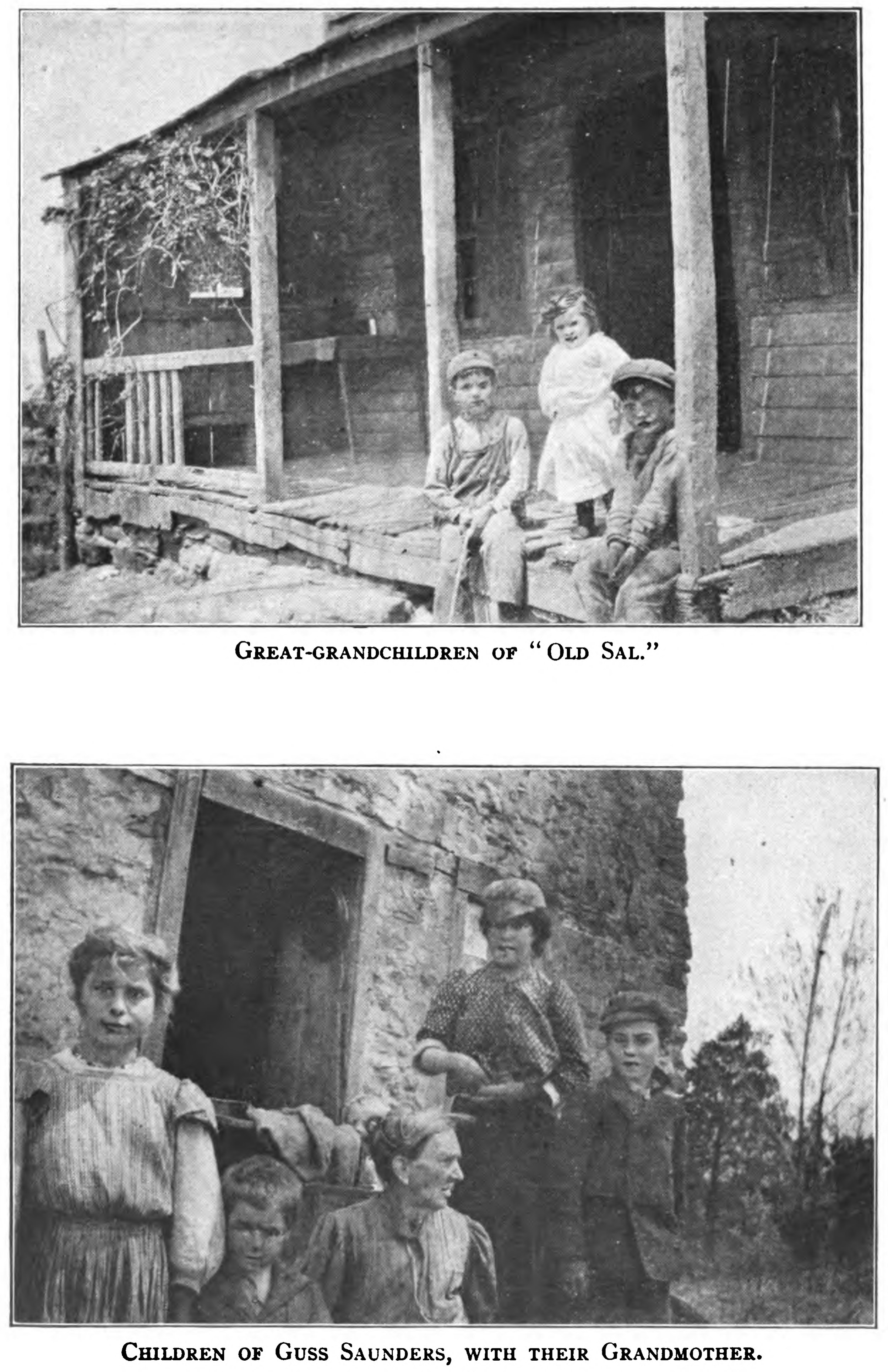

The central image of American eugenics came from the eugenic family studies. In small texts with names like The Kallikaks, The Jukes, and The Hill Folk, scientists published the results of their eugenic surveillance in narrative form. Focusing on what they called “degenerate clans,” these texts, often accompanied by photographs, utilized the hillbilly stereotype of poverty to popularize their research. As Nicole Rafter notes in her classic book on the genre, White Trash The Eugenic Family Studies 1877-1919, “The family studies gave the (American Eugenic) movement its central, confirmational image: that of the degenerate hillbilly family.”4 Nearly half of these texts were funded by the ERO.

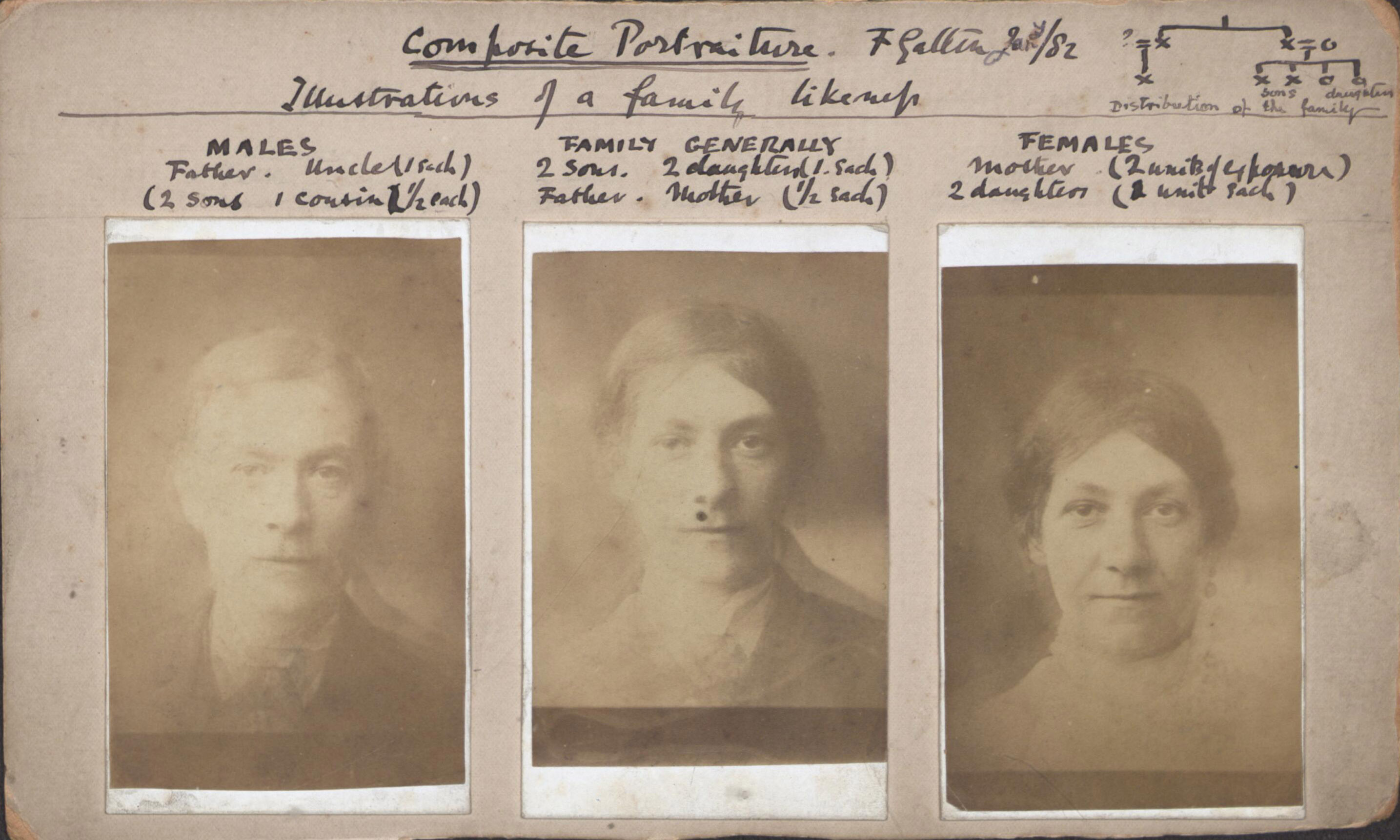

It was Sir Francis Galton, the father of eugenics, who first started the practice of producing eugenic family studies. Galton, the cousin of Darwin, invented eugenics in the 19th century from composite photographs used in his own family studies. In a process that began with circulars soliciting families to provide him with mug shot type portraits “full-face and profile,”5 Galton created ethereal composite images that he called family types. As Alan Sekula notes, “Galton sought to visualize the generic evidence of hereditarian laws.”6

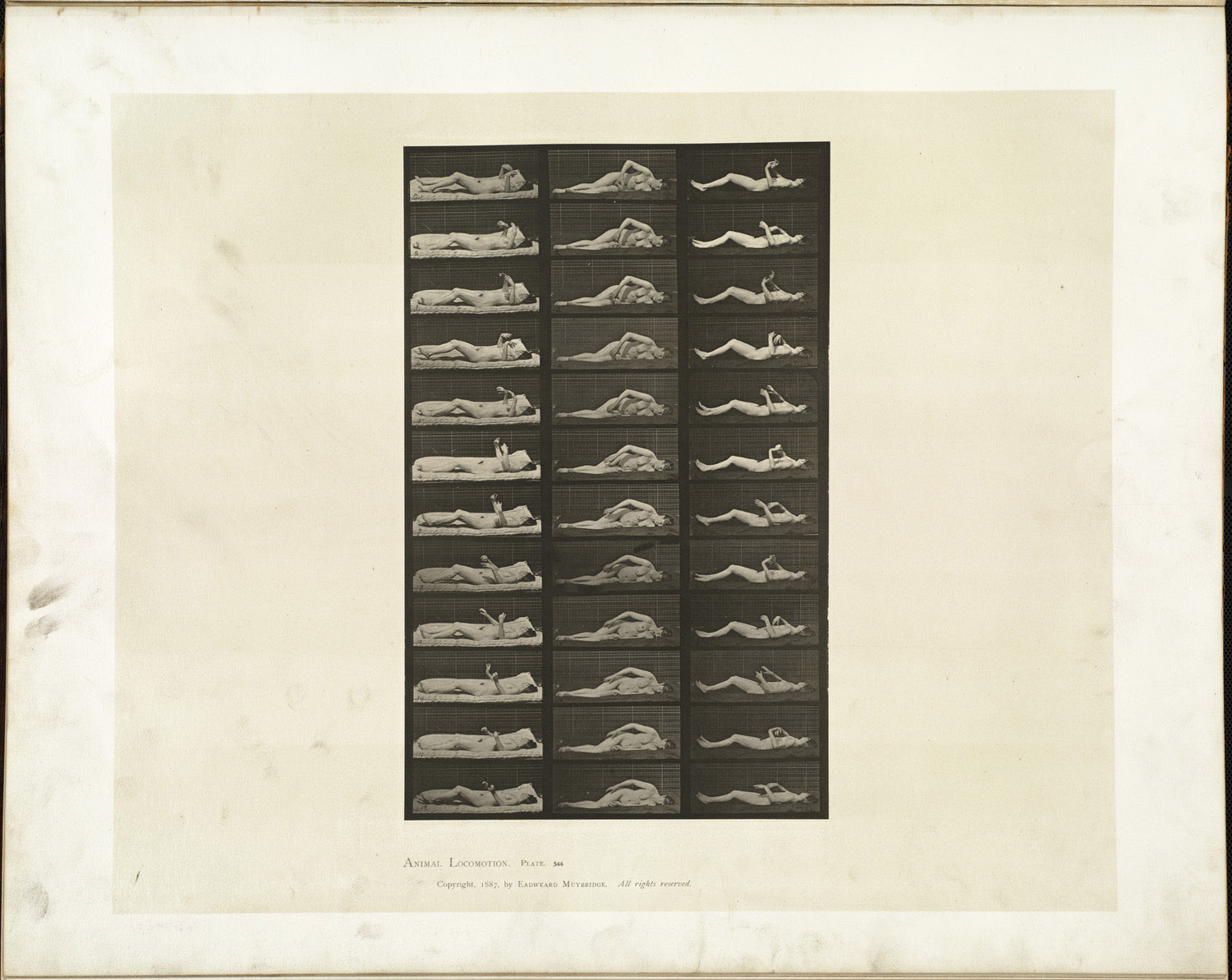

Coming at a time when the images in motion studies did not move, Galton’s images reflected the motion studies of his time. Where Marey’s and Muybridge’s motion studies were composites arranged in chronological order to show movement, Galton’s images were stacked on top of one another to show a family’s genetic variance. Like a photographic representation of the statistical bell curve, the genetic expression of each family member beyond this norm was their “movement.”

As Sekula notes, Galton’s work occurred in a historical context “of declining middle-class birth rates coupled with middle-class fears of a burgeoning residuum of degenerate urban poor.”7 In a period that included Malthus’s dire predictions of over population by the poor, Galton calmed the fears of his time. As Galton explained, “The average ability of the Athenian race is, on the lowest possible estimate, very nearly two grades higher than our own-that is, about as much as our race is above that of the African negro.”8 Galton’s most popular ethnic composite was the “Jewish type.”

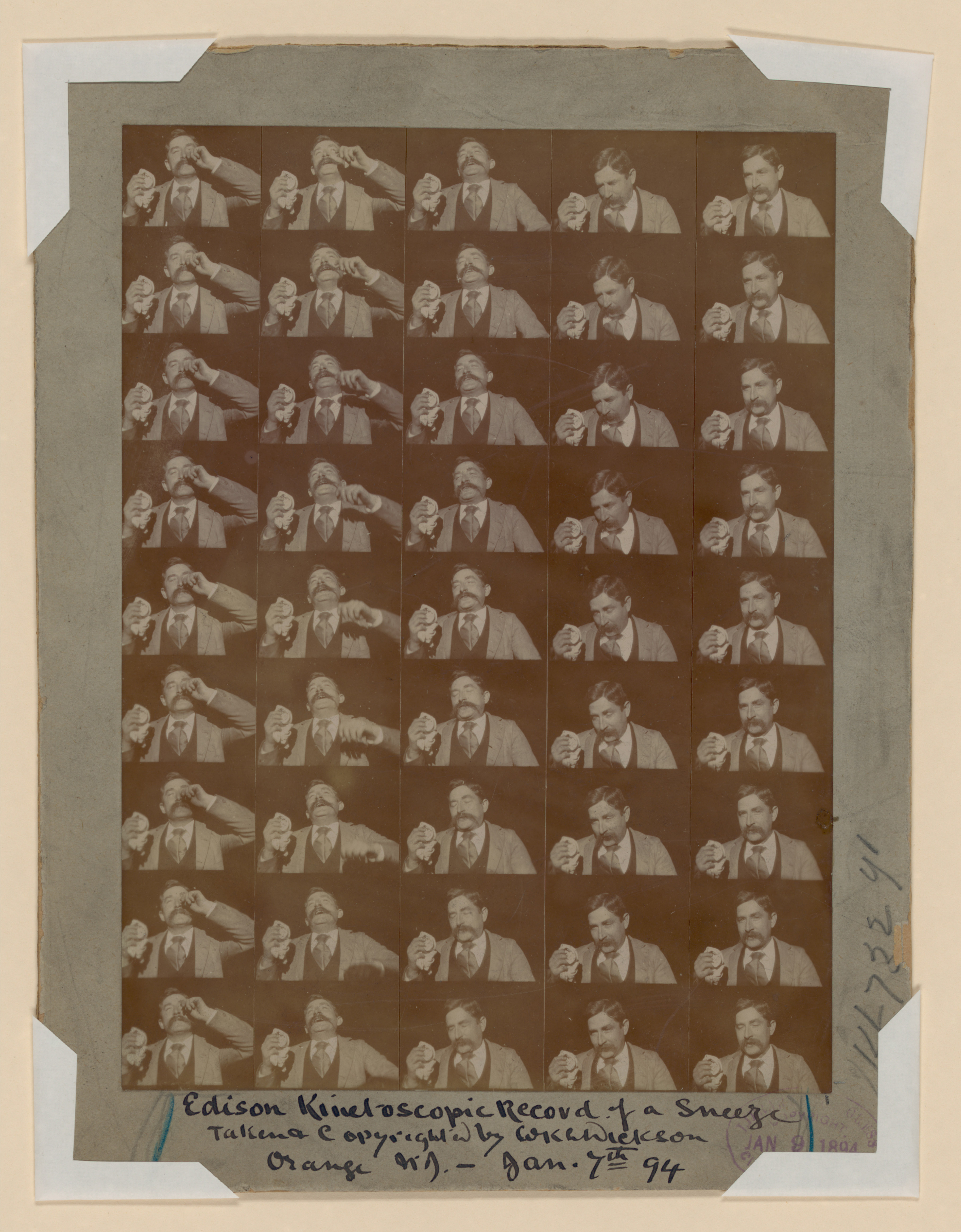

Once the mechanics of the moving image was worked out by the Lumiere Brothers and Edison, the motion studies became biographs. As Cartwright reveals in Screening the Body, Muybridge’s little known epileptic motion study made with Francis Dercum, evolved into Walter Greenough Chase’s 1905 epilepsy biographs produced at the Craig Colony for Epileptics in New York. Chase was inspired by Dercum’s work and took advantage of the new moving picture technology to expand on it. He felt the biographs offered an insight into medical knowledge of “pathologic movement” that the still image could not. With his cameras set up and 125 epileptic patients standing by, Chase was able to film 21 seizures as they occurred at the Craig Colony.

Figure 5Chase Epileptic Biograph 1905.

For Cartwright the biographs complete Foucault’s observations on the “shift in mode of visuality” between 18th and 19th century science where “we find the emergence of “life” as a cultural concept.”9 Corresponding with early film history described by Gunning as a “cinema of attractions,” Cartwright points out that the biographs were largely a cinema of “clinical” attractions. When “after 1900 Lumiere’s work…turned towards medical research and production,”10 popular cinema followed suit. Referencing what is often cited as Edison’s first moving picture, Cartwright finds that “nowhere is the popular cinema’s debt to experimental physiology and its surveillant gaze more clear than in the Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze.”11

Epilepsy was an early focus of the American eugenicists forming one of the first family “pedigrees” produced by the Eugenic Records Office. The epileptic was considered to be “the most dangerous defective with which the community has to deal, in that his acts are more or less impulsive and uncontrollable, and when he commits crimes they are usually brutal ones.”12 In society’s desire to control “defectives,” the medical biographs offered a new form of medical surveillance “that was a counterpart to the institutional practice of using photography to classify, to diagnose, and to maintain control over subjects deemed criminal, mentally ill, or otherwise aberrant.”13For Cartwright, “cinematography proved to be a technique for imputing meaning to the movements of bodies out of control.”

Chase would later produce biographs at the Massachusetts Home for the Feebleminded. Filming what he called “rhythmic idiots, each with his individual motion and keeping time to music,”14 he used the mechanical rhythm of the camera to offset and emphasize these movement disorders. This technique was developed into bradykinetic analysis, a type of slow motion analysis of movement. In addition to being used to justify eugenic sterilizations in the US, this type of neuropsychiatric film was used extensively in Germany to “serve as evidence of racial degeneracy in epilepsy and other disorders…to legitimate Nazi eugenics.”15

This brings us to Cartwright’s central argument, the “cinematic apparatus can be considered as a cultural technology for the discipline and management of the human body, and that the long history of bodily analysis and surveillance in medicine and science is critically tied to the history of the development of the cinema as a cultural institution and a technological apparatus.”16With the hillbilly stereotype in American eugenics operating as a major part of this history, Cartwright’s thesis offers a critical lens through which to view Howard’s film and Vance’s text.

In Hillbilly Elegy Vance’s text and Howard’s film treat the story of Vance’s family and its hillbilly legacy. Using Vance’s attendance at Yale Law School as its point of departure, it explores hillbilly culture from the viewpoint of someone who has escaped. In a Horatio Alger type scenario, Vance has through his own efforts risen above what plagues his community. As hillbilly themed treatments are “one of the most lasting and pervasive images of American popular culture…used by middle class economic interests to denigrate working class southern whites…”17Hillbilly Elegy as its name implies, offers a view on the death of this culture. Taking much from earlier treatments including that of the eugenic family studies, it views the hillbilly culture from a fatalistic and largely eugenic point of view.

Indeed from the beginning of Hillbilly Elegy the legacy of eugenics is present. When Netflix tells us that Vance’s memoir, “reflects on three generations of family history and his own future,” there returns the eugenic surveillant practice of framing hillbilly narratives in blocks of threes. Oliver Wendell Holmes set the standard for this practice in the 1927 Supreme Court Buck v. Bell decision legalizing eugenics. In his majority opinion he codified the practice of viewing family narratives in blocks of threes with “three generations of imbeciles are enough.”

Carrie Buck was at the center of Buck v. Bell and it was her family history that marked the beginning of this framing. Her father had abandoned the family at a young age, and her mother was seen as having had Carrie out of wedlock. When Carrie herself became an unwed mother,18 it initiated the “pattern” followed by the faulty diagnosis of her infant daughter as an “imbecile.” From this hugely problematic case the three generation model of “degeneracy” was formalized.19

This reflects how the Vance family is cast in Howard’s Hillbilly Elegy. When young JD Vance (Owen Asztalos) asks his Mamaw (Glenn Close) why they ever left Kentucky, his mother Bev (Amy Adams) answers for her, “when you’re “knocked up” at thirteen you get the hell out of Dodge.” In an admission that begins the family narrative, JD learns that his Grandmother had first become pregnant at thirteen before his grandparents were married. With his own father absent from his life, the Vance family is framed like Carrie Buck’s. JD is the third generation.

This framing of Hillbilly Elegy is followed by Howard’s presentation of the hillbilly stereotypes. At the beginning of the film we are introduced to Vance hillbilly family at an extended family gathering. There is JD’s grandmother Mamaw who in her first scene tells JD’s mother Bev “perch and swivel” while pointing her middle finger. There JD’s grandfather Papaw (Bo Hopkins), who tells his attacker “I ought to pump my foot up your ass so far you’re gonna have hemorrhoids for ten years.” While in a scene that depicts “hillbilly justice” and its culture of violence, JD explains with a bloody face, “that was our code.”

Figure 7Official Trailer for Hillbilly Elegy

This checklist of hillbilly stereotypes in many ways resembles Erskine Caldwell’s bestselling book Tobacco Road. Produced in 1932, Tobacco Road still remains one of the most popular examples of hillbilly stereotypes ever produced. Focusing on a poor, white sharecropper family in Georgia during the depression, the book was turned into a “record breaking” Broadway play and a popular movie directed by John Ford.

Caldwell presents his hillbilly checklist in the opening pages of his text. In a 50 page depiction of Ellie May seducing her brother-in-law Lov to steal his turnips, Caldwell sets up the stereotype of the Lesters. There is Pearl, Lov’s thirteen year old wife, establishing the underage bride “She was only twelve years old the summer before when he had married her.” There is the criminal family working in tandem to steal Lov’s turnips, “each of the Lesters, without a word having been spoken, was prepared for concerted action without delay.” While with Ellie May’s public seduction, Caldwell provides a lurid example of family promiscuity, “Ellie May’s acting like your old hound dog used to do when he got the itch.” In case we don’t get the message, Caldwell adds a cleft palette, providing a disturbing visual, “The upper gum was low, and because her gums were always fiery red, the opening in her lip made her look as if her mouth were bleeding profusely.” As the Saturday Review of Literature put it, “Tobacco Road is strong meat!”

It comes as no coincidence that Tobacco Road reads like a eugenic family study. As Paul Lombardo reveals in From Better Babies to the Bunglers, Erskine Caldwell’s book is adapted from his father’s eugenic study of a family he named “The Bunglers.” In a series of five articles for Eugenics: A Journal of Race Betterment, Ira Caldwell described his efforts to rehabilitate the “Bunglers.” When his efforts failed, he concluded that the “Bunglers” should be sterilized. Erskine adapted the Bungler narrative for Tobacco Road which includes two names from his father’s text, Jeeter and Dude.

After Tobacco Road, Erskine Caldwell later went on to work with the photographer Margaret Bourke-White to produce the 1937 bestseller You Have Seen Their Faces.20 With Bourke-White adding FSA styled photographs to Caldwell’s text, the book offered a factual Tobacco Road complete with pictures. Yet with Caldwell’s often fictionalized captions and Bourke-White’s use of garish flash, the book reads today like a caricature of the stereotype. With pictures of the “Bunglers” thrown in the mix, it never escapes its eugenic origins.21

Hillbilly Elegy likewise links itself to the depression era images from the FSA. Just before the Vance’s leave the family gathering, they are delayed by a family portrait. In a scene where Howard takes pains to show us how the extended family portrait is set up, even showing us the disposable camera used to make it, we are presented a series of historical photographs of “hillbilly families.”

Yet, as the bulk of images come from the Library of Congress, including two from the FSA catalogue, we are not getting the Vance family narrative or any family narrative for that matter. Instead, we are being taken into what Susan Sontag calls an “image world,” a world of “representative images, which encapsulate common ideas of significance and trigger predictable thoughts, feelings.”22 Howard is not showing us how the Vances’ see themselves, he is placing their narrative within a stereotype.

The two FSA images in Hillbilly Elegy were produced by the photographer Marion Post Wolcott. Wolcott was from New Jersey and worked for the New Deal based FSA program during the depression. In an agency headed by Columbia Professor Roy Stryker, Wolcott’s colleagues included Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and Arthur Rothstein. The FSA archive is often considered to be the most important collection of depression era photographs.

Produced in 1940, Wolcott’s two images in Hillbilly Elegy, “Noah Garland with his sons and some of their families,”23 and “Mountain Family in Porch of their home made of hand hewn logs”24 are representative of the FSA narrative of rural poverty. Taken in eastern Kentucky, they are instantly recognizable in their stylistic representation of the depression, a staple of the FSA.

Yet, if we compare these images with a series of portraits taken by Wolcott just the month before in Western Kentucky, a different narrative emerges. In a series titled “healthiest babies contest,”25 we see a narrative of eugenics. In a contest that represents what is called positive eugenics, Wolcott’s “healthiest babies contest” documents the eugenic belief that wealth and poverty correlate with eugenic heritage. Often held at state fairs, healthiest baby contests were seen by the eugenicists as a way to popularize their cause and were held across the country. Its notable that all the families participating in this contest appear to be of middle class.

In contrast, Wolcott’s image “Mountain Family in Porch of their home” shown in Hillbilly Elegy, looks more like an image of poverty than a family portrait. Produced in Breathitt County, the same county where the Vance family originates, the unaltered photograph on the Library of Congress website does not place the family at the center of the frame. If you eliminate the cropping and sepia toning in Howard’s film, the original image has as its central focus the house with its broken window. The family is not even named.

This reflects the instructions Roy Stryker gave Arthur Rothstein to intentionally photograph broken windows stuffed with rags (“it was important to show a window stuffed with rags”).26 Indeed Wolcott’s image bears a strong resemblance to her colleague Arthur Rothstein’s 1935 image of Fennel Corbin and his two grandchildren made in Virginia.27 Though it’s not known what happened to the children in Wolcott’s image, after Rothstein made his photographs of Fennel, these grandchildren were institutionalized and sterilized at the “Colony” as part of Virginia’s eugenic program.28 29

After establishing the Vance hillbilly stereotype, Howard pays token attention to their historical context. Like in his earlier effort Cinderella Man (2005), where the depression serves as visual backdrop to the story, he gives us a pretty set of visuals to denote the post war historical events that saw some 3 million Appalachian residents make their own Northern Migration to factory work.30

For Howard the migration part isn’t particularly important. Condensing this history into a few restaged scenes, Hillbilly Elegy quickly establishes that historical events are a minor part of his story. We never see Vance’s family rise to the middle class. There is nothing about the economic fallout that comes when the factories close. For Howard it’s the stereotype that is important.

Though Vance in his book also discounts the economic importance of his grandparents move to Ohio, he does describe it in some detail, even noting some of its economic benefits. Yet he too is quick to tell us that he no longer believes the narrative of lost factory jobs to understand his community’s poverty. Explaining that “Too many young men (are) immune to hard work,” he tells us that he “nearly gave into the deep anger and resentment” of his neighborhood before he found personal responsibility.

In support of this argument he quotes “one observer” to expose the root of the hillbilly problem and why it needs an elegy:

What is striking about this comment is that its author, Razib Khan, is a writer on genetics and co-founder of a blog called Gene Expression. Called out by Michael Schulson32 for promoting scientific racism he has gone so far as create a hierarchy of cultures based on their “intelligence,” a practice that started with Sir Francis Galton. Razib Khan has also been connected to the alt-right.“In traveling across America, the Scots-Irish have consistently blown my mind as far and away the most persistent and unchanging regional subculture in the country. Their family structures religion and politics and social lives all remain unchanged compared to the wholesale abandonment of tradition that’s occurred nearly everywhere else.”31

He is not alone in backing Vance’s project. Amy Chua, Vance’s mentor and professor at Yale, who encouraged him to write the book and offers “advance praise” on its back cover, has also been called out for her own cultural racism. In her book, The Triple Package, she promotes the idea that certain cultures, including her own, are superior to others.

This argument has a history. The American eugenic movement’s foundational narrative The Kallikaks offers its own similar argument. Written by Henry H Goddard and published in 1912, the book stems from Goddard’s research at the Vineland Training School for Feebleminded Children in Vineland New Jersey, where Goddard was the director. The text focuses on one of his “feebleminded” patients, a woman whom he calls Deborah Kallikak. Tracing her lineage back to Martin Kallikak, Goddard argues Deborah’s “condition” to be a result of her paternal great-great grandfather’s dalliance with a “feebleminded” Tavern girl which generations later produced “hundreds of the lowest type of humans” including herself and two epileptics. Ignoring any sort of socio-economic causes, Goddard lays the blame front and center on bad genes.

Though in Hillbilly Elegy both Howard and Vance have advanced beyond an obvious eugenic argument, indeed its made clear that JD’s intelligence originates with his mother Bev, this is a family study and Vance does connect his text to the current eugenic debate by quoting Khan. Indeed, with Bev as the prime example of dysfunctional hillbilly culture, her character contains the bulk of the eugenic checklist largely intact. There is promiscuity, drug addiction, and criminal behavior. In place of feeblemindedness there is a lack of “personal responsibility.”

After our introduction to the Vance family, we fast forward 14 years to where JD (Gabriel Basso) is about to graduate from Yale Law School. As part of JD’s internship, he is to socialize with his perspective boss and fellow students at a formal dinner. It’s a competition of sorts and there is a problem. JD has never been to a formal dinner before and doesn’t know which silverware to use.

Leaving the table, he calls his girlfriend Usha (Freida Pinto) to ask for help. She explains the forks and seems to have calmed him down, but before he returns JD’s sister calls to tell him his mother has had another heroin overdose and asks him to come home. In a scene where Howard sets up as the driving conflict of the movie, JD’s future at Yale conflicts with his hillbilly past.

After he returns JD is able to negotiate the cutlery, but the conversation proves too much. Asked what he had to overcome to attend Yale, his “hillbilly” problems quiet the table. When he ventures to reveal his connection to the Hatfield-McCoy Feud, things gets worse. The response comes: “I just saw that mini-series.”

Figure 12JD reveals his connection to the Hatfield –McCoy feud.

This quip references the recent TV portrayal of the hillbilly stereotype on the History Channel mini-series starring Kevin Costner. It creates a reflexive feel to the scene where media references media. Like a mirror we see that Hillbilly Elegy is itself part of this lineage of film productions that goes back to 1905 with Biograph’s production of the Hatfield-McCoy Feud titled, A Kentucky Feud. It’s the same year that Chase produced his epilepsy biographs supporting Cartwright’s thesis on their linkage.

But Gabriel Basso is no Kevin Costner. That is not the story here. A better fit would be Max Baer Jr. who played Jethro in the 60’s sitcom The Beverly Hillbillies. Like Jethro, JD is a displaced hillbilly that doesn’t know the ways of high society. This is the narrative Howard is more familiar with from his days at The Andy Griffith Show.

The Beverly Hillbillies was part of a series of TV programs in the 1960s, including The Andy Griffith Show, that brought the hillbilly narrative to television. The narrative centered around the Clampett family which had moved to Beverly Hills after they had become rich when oil was found on their land. That the Clampetts are wealthy and yet maintain their hillbilly ways provides the bulk of the jokes.

Adapted in part from Caldwell’s Tobacco Road, the sitcom turns Caldwell’s lurid stereotypes into comedy, like the film and Broadway adaptations before it. Paul Henning, the creator of the Beverly Hillbillies is reported to have been influenced by the Broadway production of Tobacco Road he saw in Kansas City.33

Though Ellie Mae in his version doesn’t have a harelip or drag herself across the front yard, Henning makes her relationship to men ambiguous enough to suggest the stereotype. With Grandma’s staple of possum stew we are not far from the Lester family’s starvation diet of soup made from fat-back rinds with corn bread. With Max Baer Jr. cast as Jethro we also have a reference to hillbilly violence. Baer’s real life father Max Baer was the prize fighter brutally portrayed in Howard’s Cinderella Man.

After The Beverly Hillbillies was cancelled in the early 70’s as part of television’s “rural purge” there emerged in the theaters one of the best known film versions of the hillbilly stereotypes, Deliverance in 1972. Based on James Dickey’s screenplay of his novel, Deliverance was produced and directed by John Boorman, and starred Burt Reynolds, Ned Beatty, Jon Voight, and Ronny Cox.

Figure 14Dueling Banjo Scene from Deliverance

In one of the most iconic scenes from Deliverance we are given an image straight out of the eugenic family studies. When Drew, played by Ronny Cox, plays dueling banjos with Lonnie played by Billy Redden, its clear that Billy Redden has been chosen to play the role of the inbred hillbilly. Redden is a fifteen-year-old special education student that has had his head shaved and skin powdered to fit the part. The second draft of Deliverance describes Redden’s character as “probably a half-wit, likely from a family inbred to the point of imbecility and Albinism,”34 a description that seems written by a eugenicist. The scene even offers us a look through a tattered window to see a local mountain woman cradling her sickly child who in reality is her mentally disabled grandchild.35 By looking through the window we demonstrate Cartwright’s observation that “surveillant looking and physiological analysis…are not just techniques of science. They are broadly practiced techniques of everyday public culture.”36

To complete the stereotype we get the most notorious scene, the rape scene with the unforgettable line, “squeal like a pig.” Adding sexual deviancy and violence to mental disability, Deliverance completes the eugenic checklist. Coming at a time when homosexuality was designated as deviant behavior in the DSM II, this “deviancy” is linked to the hillbilly’s inbred eugenic heritage. With a nod to Caldwell, there is even the facial deformity of missing teeth paraded in front of the camera reflecting Ellie May’s cleft palette. Here, Deliverance projects a need to control these “defectives” and we are relieved when Lewis Medlock (Burt Reynolds), kills one with his bow and arrow.

There is a very real link between Deliverance and Hillbilly Elegy. In an example of institutional memory where the financial success of Deliverance spawned a film industry in Georgia, the scenes in Hillbilly Elegy depicting the Vance family’s origins in Kentucky are in fact shot in Rabun County, Georgia; the same county where most of Deliverance was shot. As if returning to the scene of the crime, when young JD is ambushed in the water and has his face bloodied, it is in the same waters where Lewis, Bobby, Ed, and Drew were attacked in Deliverance. That the Vance family portrait is produced in the county that the Deliverance script describes as populated by “half-wit inbred imbeciles” offers a reinforcement of the stereotype.

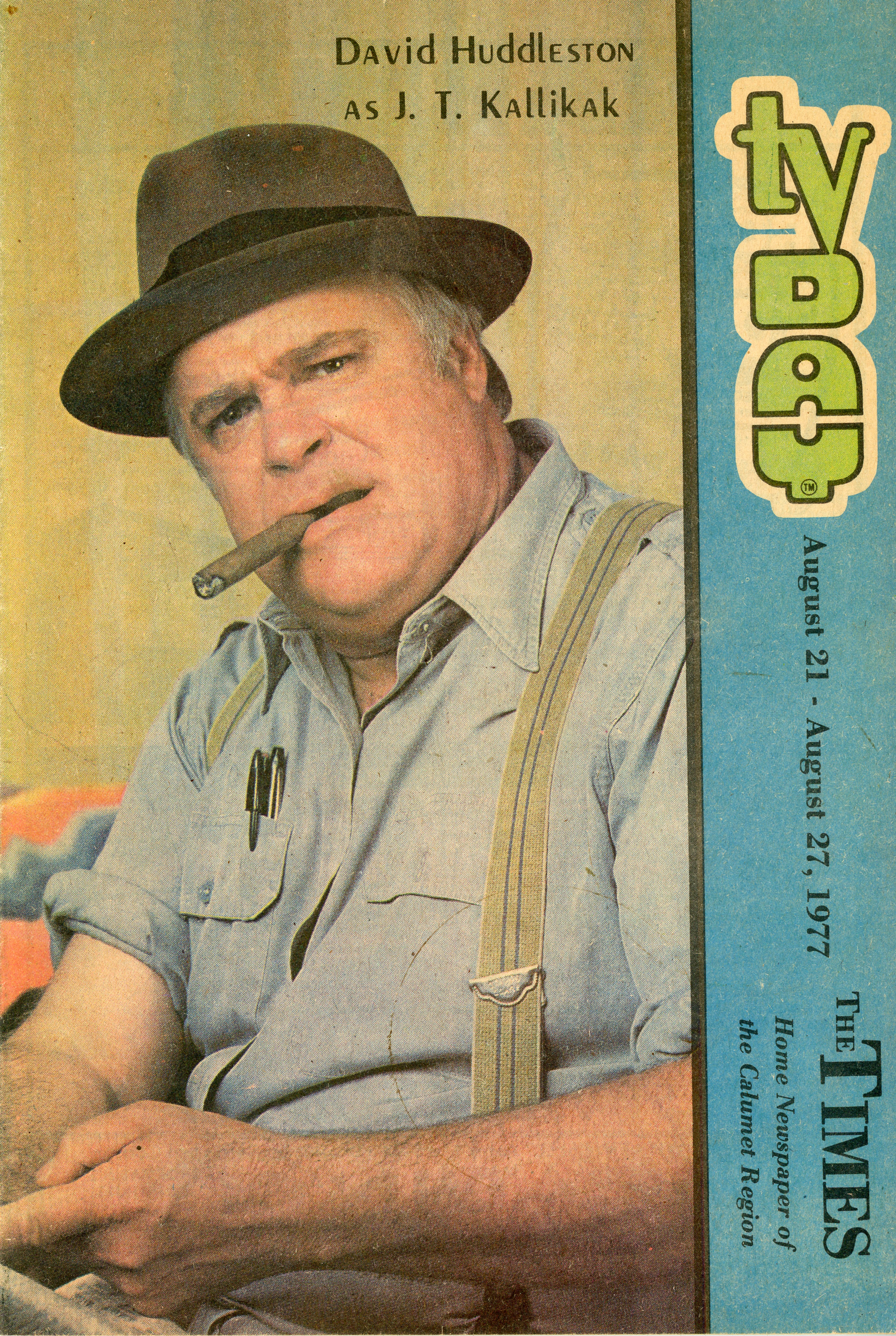

In the late 1970s there was an attempt to revive the hillbilly narrative for another program. Switching back to comedy, the hillbilly narrative and its link to eugenics returned to television. As if intentionally demonstrating this connection, there premiered in the summer of 1977 a sitcom actually named The Kallikaks. Produced by Emmy Award winner George Yanok, and starring Buddy Ebsen’s daughter Bonnie Ebsen with David Huddleston, The Kallikaks’s narrative centered on a family from Appalachia that had moved to California to run a gas station. Though it had a short run, the program was heavily promoted, appearing on the cover of TV guides around the country. Stephen J. Gould, author of The Mismeasure of Man,37 calls Goddard’s The Kallikaks “the primal myth of the eugenics movement.”

This raises important questions about Ron Howard’s input as the director of Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy. With Howard’s extensive TV and film experience starting with Opie in The Andy Griffith Show, he has both acted in a hillbilly themed sitcom and directed a memoir of hillbilly culture through Vance’s text.

The Andy Griffith Show first aired in 1960. Casting Andy Griffith as Andy Taylor as the town sheriff of Mayberry presiding over his “comic” hillbilly neighbors; with Opie (Ron Howard) in the role of his son, it was set in the fictional town of Mayberry in North Carolina near the southern Virginia Appalachian Mountains. As the Sheriff of Mayberry, Andy Taylor functions largely as a corrective. When things get out of hand Andy puts things back in order. This is especially true with hillbillies. Epitomized by the character of Ernest T. Bass (Howard Morris), “every encounter (Bass has) with civilization inevitably proves disastrous and each episode closes with Sherriff Taylor hastening him back to the mountains hoping he will not return.”38

When in later years Andy Taylor marries the local school teacher Helen Crump (Aneta Corsaut), Bass has disappeared and this corrective has expanded to reflect the real life professional alliances that together controlled the “degenerate” hillbilly. Along with doctors and social workers, the police and school teachers acted to contain the public’s “fears of a burgeoning residuum of degenerate … poor.” This fear had at its core the Kallikak family. As the prominent Virginia eugenicist Dr. DeJarnette wrote in 1935 about an Appalachian family, “if this one family which I visited be allowed to propagate in six generations it will dethrone the Jukes and the Kallikaks… The welfare workers are cooperating with us in an effort to sterilize the whole family.”39

Howard has his own fear of the poor that comes out of the depression,

The quote comes from an interview made when promoting his film Cinderella Man, starring Russell Crowe. Set in the 1930s, Cinderella Man focuses on the real world story of James J. Braddock’s heavyweight title fight with Max Baer during the depression. The same Max Baer who was the father of Jethro in The Beverly Hillbillies. Like Howard’s treatment of the Vance family’s migration to Ohio, historical events operate only a backdrop for “teaching values,” the most important of which as expressed by Braddock (Russell Crowe) to his son when he steals food, “we don’t steal.” There is no fight to end poverty, no strikes to form a union, no argument with fascism. The answer to the depression is an underrated boxer who defeats the “murderer” Max Baer and pays back his government assistance.“I’ve always been interested in the Depression as this very dramatic pivotal period in American history. My dad grew up on a farm in Oklahoma and remembers playing with his toy tractor under the table while the local farmers talked with his grandfather about forming a local militia to protect the crops because they were afraid unemployed people from the town would come in and grab the crops.”40

Howard’s framing misses the big picture. Max Baer did famously fight fascism. Before fighting Braddock, Baer defeated Hitler’s favorite Max Schmeling for the title while wearing the Star of David on his shorts. Considered to be the only Jewish heavy weight champ, “Schmeling was beaten by a man who in Germany would be classified as a Jew.” So too did Braddock’s next opponent, Joe Louis. After he beat Braddock, Louis went on to defeat Schmeling in a fight that further challenged Hitler’s racist and eugenic ideals. Yet in Howard’s film this is not even mentioned. For Howard its all about not stealing food.

This focus further aligns Hillbilly Elegy with Tobacco Road. Caldwell expresses similar sentiments in Tobacco Road where he offers his view on the criminality of the poor through Jeeter, the patriarch of the Lester family.

Like Howard, Caldwell has no sympathy for starvation. When he notes that Ada and the grandmother both suffer from pellagra, a painful debilitating disease that comes from a poor corn based diet, he presents it as a moral failing. He sees their looming death as a stubborn resistance to the inevitable march of progress. “The pellagra that was slowly squeezing the life from her was a lingering death. The old grandmother had pellagra too, but somehow she would not die.” There is no acknowledgement that pellagra was epidemic in poor southern communities during the depression. Instead he aligns himself with the ERO’s stance that asserted pellagra was a eugenic disease.42“Jeeter had long before come to the conclusion that the only possible way a quantity of food could be obtained was by theft. But he had not been able to locate a turnip patch that year within five or six miles. There had been planted a two-acre field the year before over at the Peabody place, but the Peabody men had kept people out of the field with shotguns then, and this year they had not even planted turnips.”41

With Hillbilly Elegy it is opioid epidemic that provides the morality tale. With Bev as the centerpiece for the argument for personal responsibility, Howard makes sure we get the message that her opioid addiction is her fault. He ignores the fact that her addiction is occurring in the middle of a major opioid epidemic. Like in Cinderella Man, Howard has put his blinders on and Middletown is essentially a prop. When Bev gets high and puts on roller skates after her father’s death, she is a woman out of control disrupting the social order.

It is here that Howard’s film takes on its real task of “imputing meaning to the movements of bodies out of control.” With her opioid addiction, Bev’s increasingly erratic behavior motivates the changes that give meaning to his film. Through Mamaw’s intervention JD learns what is “important.” As in Cinderella Man what is important is not to steal and not to take public assistance. Mamaw then gives JD a model for his behavior in Arnold Schwarzenegger from Terminator 2. She tells JD, “There are three types of terminators, good, bad, and neutral.” When JD at the end places his homeless opioid addicted mother in a motel, this all comes to fruition. When JD tells his mother “I’m not saving anyone here,” he has freed himself to become a venture capitalist. This is an elegy and JD is a good terminator.

In the end Howard’s film simply extends the stereotypes of historical hillbilly constructions and with it their eugenic framings. Like in Caldwell’s Tobacco Road, his subjects’ problems are treated as moral failings in counter example to that of JD’s success. As if to show us he is aware of these representations he even inserts the reflexive Hatfield-McCoy discussion in Hillbilly Elegy to take us back to the beginning of film history. This history leads to Mamaw’s Terminator 2 metaphor where “cinema’s debt to experimental physiology…”43becomes embodied in a dystopian cyborg.

Yet, Howard seems to not understand or care how these representations work. Rather than unwrapping them he uses them as props, ignoring Vance’s counter representations. Perhaps because of his upbringing in The Andy Griffith Show, media is treated as a type of historical progression obscuring the real world. In Howard’s film, Deliverance and Terminator 2 inform Hillbilly Elegy more than the mass migration event that brought the Vances to Ohio.

But JD is no better. In his “family study” Vance gives cover to those behind the problems of his community offering up his own family as a “negative counter example” fashioning himself in the Horatio Alger myth. Explaining that “too many young men (are) immune to hard work,” he presents the problems of his community as connected to its hillbilly code, not the lost factory jobs in the wake of NAFTA. Utilizing his hillbilly credentials, he puts his mother on display to disavow the opioid epidemic’s devastation. And while not a eugenic family study, Hillbilly Elegy taps into the genre’s arguments, linking itself to the revival of the eugenic debate currently tied to the alt-right.

Vance’s recent endorsement by Trump further reveals the influence of his backers. He no longer explains Trump to a nervous public afraid of hillbillies, but follows him. Now, the fear he is selling is of the left. Using some of the very problems he disavowed in Hillbilly Elegy he is exploiting the fears of his Ohio “hillbilly” constituents to drive his campaign. Backed by billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel, Vance has become a “fearless MAGA fighter” against the corporate progressivism epitomized by NAFTA. When he proclaims a desire to break up the big tech industry, Vance seems more informed by the data mining analyses of his constituents than any personal conviction.

Notes

- Charles Davenport, “Heredity in Relation to Eugenics” Charles B. Davenport Papers. Breeders Association Files. (1907). iii. ⮭

- Daniel J. Kelves, In the Name of Eugenics. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1985), 54. ⮭

- Wendy Kline, “A New Deal for the Child: Ann Cooper Hewitt and Sterilization in the 1930s” in Popular Eugenics, National Efficiency and American Mass Culture in the 1930s, ed. Sue Currell and Chirstina Cogdell (Ohio University Press, 2008), 24. ⮭

- Nicole Rafter, White Trash The Eugenic Family Studies 1877-1919, (Boston: Northeastern University Press., 1988), 2. ⮭

- Sir Francis Galton, “Circular Letter.” Letters about Composite Photographs 1877-1932. Galton Papers, University College London. Wellcome Collection. ⮭

- Alan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive.” The Contest of Meaning. Ed. Richard Bolton, (Boston: MIT Press, 1989), 354. ⮭

- Ibid, 365. ⮭

- Francis Galton, Hereditary Genius (London:Friedman, 1978), 342. ⮭

- Lisa Cartwright, Screening the Body. Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 10. ⮭

- Ibid, 1. ⮭

- Ibid, 13. ⮭

- Djem Kissiov, et al. “The Ohio Hospital for Epileptics-the first “epilepsy colony” in America.” Epilepsia vol. 54,9 (2013): 1524-34. doi:10.1111/epi.12335. ⮭

- Ibid, 4. ⮭

- Walter Greenough Chase, “The Use of the Biograph in Medicine,” Boston Medical and Surgical Journal 63, no.2 (1905) http://doi.org/10.1056/nejm190511231532101. ⮭

- Lisa Cartwright, Screening the Body. Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 73. ⮭

- Ibid, 4. ⮭

- Anthony Harkins, Hillbilly, A Cultural History of an American Icon (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 4. ⮭

- Paul Lombardo, “Facing Carrie Buck.” The Hastings Center Report, vol. 33, no. 2, (2003), pp. 14–17, https://doi.org/10.2307/3528148. ⮭

- Ibid. ⮭

- Erskine Caldwell and Margaret Bourke-White, You Have Seen Their Faces (New York: Modern Age Books Inc., 1937). ⮭

- Paul A. Lombardo, “From Better Babies to the Bunglers: Eugenics on Tobacco Road” in A Century of Eugenics in America: From the Indiana Experiment to the Human Genome Era ed. Paul A. Lombardo (Indiana University Press, 2011). ⮭

- Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2003), 86. ⮭

- Marion Post Wolcott, photographer, Noah Garland with his sons and some of their families. Southern Appalachian Project near Barbourville, Knox County, Kentucky. United States Barbourville Kentucky Knox County, 1940. Nov. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017805740. ⮭

- Marion Post Wolcott, photographer, Mountain family on porch of their home made of hand hewn logs up South Fork of Kentucky River, Breathitt County, Kentucky. United States South Fork Kentucky River Breathitt County Kentucky, 1940. Sept. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017805027. ⮭

- Marion Post Wolcott, photographer, Untitled photo, possibly related to: Healthiest baby contest at Shelby County Fair and Horse Show, Shelbyville, Kentucky. United States Shelby County Shelbyville Kentucky, 1940. [Aug.?] Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017756466. ⮭

- Richard Doud, Oral history interview with Arthur Rothstein, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. May 25, 1964. ⮭

- Arthur Rothstein, photographer. Fennel Corbin and two of his grandchildren, Shenandoah National Park, Virginia. United States Shenandoah National Park Virginia, Oct 1935. Photograph. https://www.loc.gov/item/2017721580. ⮭

- Richard Robinson, “Rothstein’s Family Portraits.” (Exposure Magazine, Society for Photographic Education, Spring 2017), 38. ⮭

- Sue Currell, “You Haven’t Seen Their Faces: Eugenic National Housekeeping and Documentary Photography in 1930s America.” (Journal of American Studies, 2017), 51(2), 481-511. doi:10.1017/S0021875817000366. ⮭

- Anthony Harkins, “The Hillbilly in the Living Room: Television Representations of Southern Mountaineers in Situation Comedies, 1952-1971.” (Appalachian Journal Fall 2001), 4. ⮭

- JD Vance, Hillbilly Elegy (New York: Harper Collins, 2016), 3. ⮭

- Michael Schulson, “Race Science and Razib Khan,” Undark, Feb 28, 2017, https://undark.org/2017/02/28/race-science-razib-khan-racism. ⮭

- Anthony Harkins, “The Hillbilly in the Living Room: Television Representations of Southern Mountaineers in Situation Comedies 1952-1971.” (Appalachian Journal Fall 2001), 111. ⮭

- James Dickey, “Deliverance, Screenplay Second Draft,” (January 11, 1971), 13. http://www.dailyscript.com/scripts/deliverance.pdf. ⮭

- S. Keith Graham, “Twenty Years after Deliverance: A Tale of a Mixed Blessing for Rabun County,”(Atlanta Journal-Constitution, March 18, 1990), M4. ⮭

- Lisa Cartwright. Screening the Body. Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. 1995), 5. ⮭

- Stephen J Gould. The Mismeasure of Man. (New York: W. W. Norton and Company; 1981), 198. ⮭

- Anthony Harkins, “The Hillbilly in the Living Room: Television Representations of Southern Mountaineers in Situation Comedies, 1952-1971” (Appalachian Journal Fall 2001), 107. ⮭

- Western State Hospital, Virginia. Lynchburg State Colony, C. Annual report of the Western State Hospital. Richmond:1935. ⮭

- Dave Zirin, “Crass Slipper Fits Cinderella Man,” Visual Economies Of/in Motion: Sport And Film, Ed. C. Richard King and David Leon. (New York: Peter Lang, 2006), 196. ⮭

- Erskine Caldwell. Tobacco Road (New York: Grosset and Dunlap, 1932), 6. ⮭

- Though virtually unknown today, pellagra was an epidemic during the depression. Known for the four d’s, dermatitis, diarrhea, dementia and death, it devastated poor communities throughout the South. After Dr Goldberger’s demonstrations of its link to nutrition, the ERO’s Charles Davenport inserted his influence on the President’s Pellagra Commission to claim that its cause was instead eugenic. In what Allan Chase in The Legacy of Malthus calls “The Medical Fraud of the Century,” the professional interests of the ERO derailed the work of Goldberger delaying pellagra’s eradication for over twenty years. ⮭

- Lisa Cartwright, Screening the Body. Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1995), 13. ⮭