[They] started us out doing kind of a thought experiment where we had sticky notes and we put them up on the wall. …That was a really good thought experiment and we actually keep going back to that …while a lot of our courses have learning goals, we don’t really have learning goals across our major. So we started developing some strategies for how to try to address that.

—(Sophia, Runes DAT Member)

Although hundreds of science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) educational change efforts have been documented in recent years, many efforts have been guided by overly simplistic models of change, which has limited their capacity to effect widespread, sustainable changes (Henderson et al., 2011). For instance, a single faculty member may redesign a course only to be rotated out of the course one to two years later. As a result, innovations are often forgotten and replaced. Thus, there is a pressing need to develop robust models for change in higher education (Kezar, 2011; Reinholz et al., 2020).

We developed the Departmental Action Team (DAT) model, drawing on research on organizational change (Reinholz et al., 2017; Reinholz, Pilgrim et al., 2019). A DAT is a small group of faculty, students, and staff guided by one or two external facilitators that collaboratively work within a department to bring about sustainable improvements to education. We have extensive experience using the DAT model in dozens of departments across multiple campuses (Reinholz et al., 2018).

DAT work is guided by six core principles (Quan et al., 2019). This article is organized around one of them—a focus on outcomes. To align and motivate their collective work, DATs develop a shared vision. This vision focuses the group on positive outcomes to be achieved rather than on isolated problems to be solved. A focus on outcomes helps DATs negotiate conflict and stay focused on what they hope to achieve.

We present examples of five DATs to illustrate the impact of focusing on outcomes. This general approach can be incorporated into nearly any change process. Thus, this article contributes to the efforts of other educational change agents by illustrating an important theoretical principle for guiding change and how it can be implemented in practice.

Theoretical Background

Organizations are complex systems that are made up of many smaller interacting parts that contribute to organizational learning, decision-making, and change (Argyris, 1992; Wasserman, 2010). Universities, like organizations, consist of many individuals who may have competing priorities, goals, motivations, and expertise. Thus, organizational change research provides a useful starting point for understanding how change occurs in universities and guidance for how planning and decisions are made (Reinholz, Matz et al., 2019; Reinholz et al., 2020).

Strategic planning, which involves building a vision and developing plans to achieve that vision, is one method that guides organizational decision-making (Taylor & Karr, 1999). Strategic planning helps guide and constrain decision-making because it sets what should be achieved and how to achieve it. Strategic planning also plays an important role in higher education (Elrod & Kezar, 2015). Effective strategic planning involves a wide variety of relevant stakeholders and is flexible enough to allow for emergent outcomes (Elrod & Kezar, 2015; Henderson et al., 2011; Kezar, 2014). As in business, strategic planning in higher education ideally generates a clearly articulated vision. However, this is not always the case, and even the clearest visions need to be adapted over time to changing circumstances. Thus, a vision is not something that is simply set once and followed but is something that can be continually revisited and adjusted as necessary. The central thesis of this manuscript is that visions should be co-developed by department members and other relevant stakeholders, with the aim of determining positive outcomes to be achieved.

Focus on Outcomes

Studies of individual and organizational change draw attention to the benefits of groups focusing on positive outcomes they wish to achieve rather than problems they wish to fix. A typical problem-solving cycle often leads to intensifying the problem (Fritz, 1989). The cycle is as follows: (1) a problem leads to action to solve the problem, which (2) reduces the intensity of the problem, which (3) reduces the actions taken to solve the problem, which (4) leads to the persistence of the problem. Therefore, to address the issue, it is necessary to break out of the problem-solving cycle and instead focus on a significant outcome, which may alter or eliminate some of the sources of problems. In general, when it comes to large, persistent problems in education, they cannot simply be “solved” without attention to root causes.

Because individuals default to focusing on problems, some forms of therapy and individual coaching work by explicitly focusing clients on outcomes (e.g., solution-focused therapy; Kim, 2008). These approaches diverge from the traditional paradigm of analyzing problems and past events to instead help individuals identify and clarify their goals (de Shazer & Dolan, 2012). The process begins with a focus on what the client is doing, with explicit recognition of what is positive and can be built upon to achieve the individual’s goals. Moving from the individual to organizational level, similar techniques are used in Appreciative Inquiry, which builds on what is positive to support an organization’s development (Cooperrider et al., 2008).

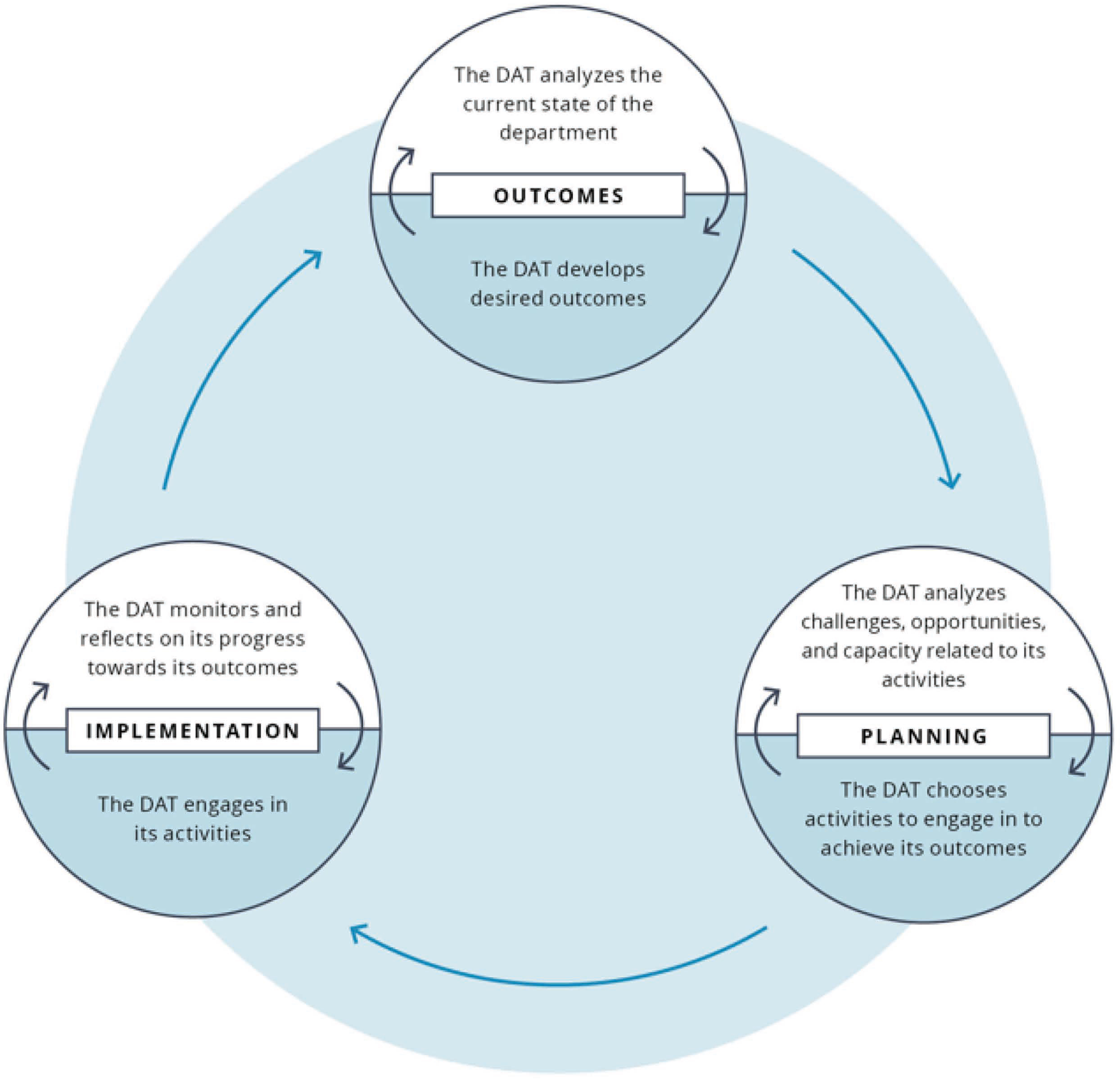

Similarly, to achieve lasting improvements within departments, DATs use a change cycle to guide work that is focused on outcomes rather than problems (see Figure 1). The first step of the cycle is visioning to determine the desired outcomes. Through this process, the DAT analyzes the current state of the department while attending to what is positive in the department and can be built upon. The second step of the cycle involves planning activities to support the desired outcome. This step often involves collecting and analyzing data to understand the likelihood that particular activities will be successful. The third step is implementation, in which the DAT engages in concrete activities to build toward the desired outcome while also monitoring and reflecting on its progress. A DAT may go through many cycles of determining outcomes, planning activities, implementing, and reflecting.

Table 1 contrasts the idealized steps involved with a change process focused on problems compared to a process focused on outcomes. An outcome focus draws attention to “what is wanted,” which contrasts with a problem focus on “what is wrong.” Although these are two distinct approaches to change, there are some potential areas of overlap. For instance, both outcome-focused and problem-focused approaches might rely upon data. However, the use of data would differ. From a problem-solving perspective, data would be used to identify the problem and subsequently provide evidence that the problem had been solved. From an outcome-focused perspective, even if data provided evidence of progress toward a particular solution, the work would not be considered complete. Rather, the data would provide a benchmark that would support continuous improvement. Given that change processes related to outcomes and problems can have areas of overlap, facilitators must make explicit efforts to keep the group focused on outcomes. Table 1 shows an idealized process, but in reality, these steps are nonlinear, and change processes need not necessarily include all steps. In the next two subsections, we outline the theory behind these processes in more depth, including the role of facilitation.

Problem-Solving-Focused vs. Outcome-Focused Processes

| Problem-solving process | Outcome-focused process |

|---|---|

| Identify a problem and analyze causes | Build a vision to determine outcomes |

| Plan solutions to the problem | Plan activities to achieve the outcomes |

| Implement solutions | Implement activities and reflect on progress |

Problems With the Problem-Focused Process

A focus on problems begins with identifying the problem. As with individual learners, adopting a deficit perspective is limited, because it ignores the productive resources that learners have that can be used to construct new understandings (Smith et al., 1993–1994). Similarly, focusing on what is wrong in an organization leads to disagreement without providing a productive springboard for future work. Once identified, a team analyzes causes for problems but is often ill equipped to do so, given the complexity of persistent problems in education. As a result, decision-making tends to be guided by a variety of sometimes faulty heuristics (Kahneman, 2011). For instance, individuals rely on personal anecdote and bias, which leads them to draw on accessible—rather than representative—examples to explain phenomena. Similarly, individuals typically see their own decisions as situated within complex social contexts yet attribute the actions of others to simplistic internal characteristics such as laziness—a phenomenon known as attribution error (Ross, 1977). To overcome these faulty heuristics, effective root cause analysis requires a formal evidence-based process (e.g., Elrod & Kezar, 2015).

The second step for solving a problem is to plan solutions to the problem. At this stage, individuals typically default to their own preferred solutions to the problem, based on how they perceive it. This tendency relates to cognitive biases including confirmation bias (the tendency to seek out information in favor of one’s pre-existing beliefs; see Oswald & Grosjean, 2004) and the law of the instrument (“when you have a hammer everything is a nail”; see Maslow, 1966, p. 15). Critically, if at this step multiple proposed solutions are incompatible, then collaboration will be inhibited. For example, a proponent for course-based response systems (i.e., “clickers”) may see them as a tool that can be used to solve a variety of problems, whereas other team members may prefer to focus on classroom norms or techniques to pro-mote equitable participation. Unless the group has a clearly defined goal, typically it will have no systematic way of choosing among the potential solutions, which could lead to gridlock, or different solutions being implemented inconsistently.

The third step is to implement solutions. It is often assumed that this is a final step and that the problem will stay solved. Underlying this assumption is a view of change as an event rather than a process. Once a change event happens, it is assumed that the change will remain, because the improvement represents a transition from one state to another. Research on organizational change challenges this simplistic notion, instead emphasizing that change is an ongoing process of improvement (Reinholz, Ngai et al., 2019; Senge, 2006). Given the limitations of the problem-solving perspective, a problem focus is unlikely to address complex issues of departmental change. While smaller issues may be solved through this approach, the persistent, systemic problems of education cannot be solved this way.

Outcome-Focused Perspective

The first step is to build a vision and determine outcomes. The visioning process can be decomposed into a variety of different facets. At the most general level, a group may first determine what it values. These value statements describe the priorities, interests, and commitments of the group and allow the group to start from a place of agreement rather than disagreement (Cooperrider et al., 2008). These values can then be translated into a more elaborated vision that highlights a positive imagined future (Lucas, 1998). The vision provides a signpost that can be revisited to ensure that a group remains on the same page throughout a change process. Finally, the vision is made tangible through concrete outcomes that describe the things that need to be accomplished to achieve the vision. Determining outcomes may involve a combination of divergent discussion—eliciting a wide variety of ideas—and convergent discussion—figuring out which of the myriad goals should be prioritized first.

The second step involves planning activities to achieve the desired outcomes. Again, this process typically involves a combination of divergent and convergent discussions. Because the possible actions are guided by an underlying vision and goals, it promotes flexibility by helping team members envision a number of actions that could be possible (Garmston & Wellman, 2016). The planning process also tends to involve data collection and analysis that can inform the activities that will be undertaken. Finally, the planning must also include conversation with department leadership and relevant departmental committees to ensure that whatever activities the group engages in are likely to be supported and taken up by the department.

The third step involves implementing activities to pursue the goals. As group members get deeper into the change cycle, they often realize the necessity of a continuous improvement process, because their goals require constant continued effort to be achieved. This realization helps a group design their change work for sustainability early on. A focus on outcomes and continuous improvement also orients a group toward assessing the impacts of their work. As a team implements particular actions, it collects data to assess the extent to which it is achieving its goals and uses data to further act in support of its vision.

Departmental Action Teams

Overview of the Model

A DAT is a self-selected group of faculty, students, and staff within a single department that meets every other week for multiple semesters. The DAT uses change cycles to sustainably improve their departments. External facilitators support a DAT with their expertise on education and organizational change, connections in the local context, skills in interpersonal communication, and their ability to coordinate logistics and help run meetings. Facilitators guide DATs to embody six core principles that describe ideal characteristics of departmental culture that support change (Quan et al., 2019):

Students are partners in the educational process.

Work focuses on achieving collective positive outcomes.

Data collection, analysis, and interpretation inform decision-making.

Collaboration between group members is enjoyable, productive, and rewarding.

Continuous improvement is an upheld practice.

Work is grounded in a commitment to equity, inclusion, and social justice.

These principles are shared with DAT members and are explicitly included as part of the change process. Facilitators also help DAT members develop a deep understanding of the change cycle. As DAT members learn more about how to enact change, they become empowered as agents of change who can continue to work effectively even after the DAT disbands. Of particular relevance to this manuscript is Principle 2—building a shared vision and focusing on outcomes.

Visioning in DATs

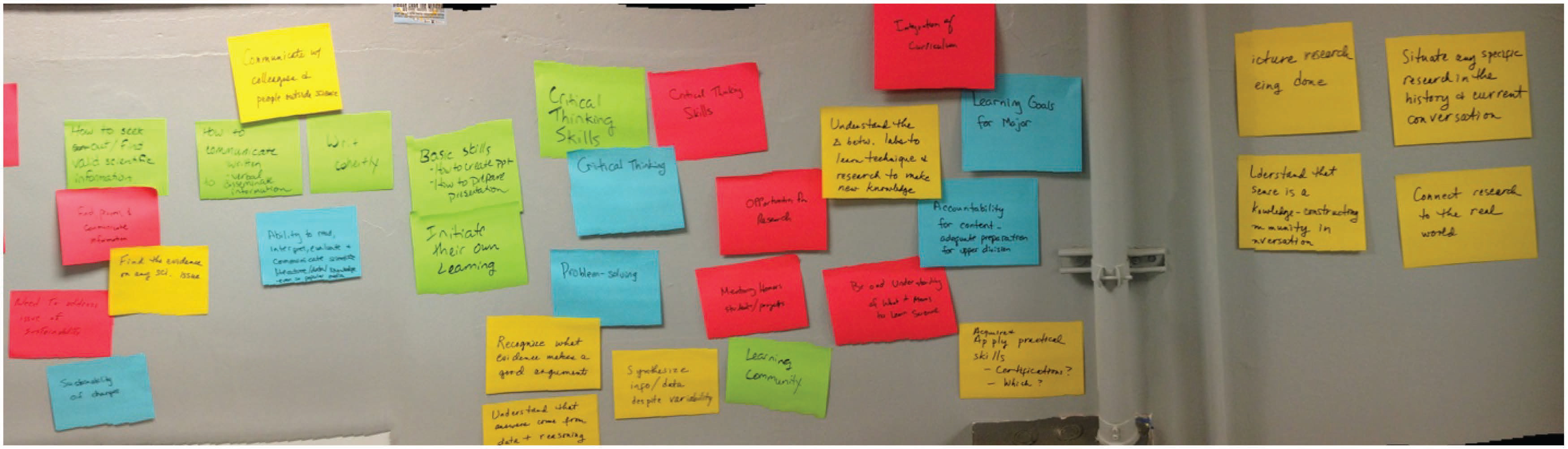

All DATs begin with an ideal future visioning activity. Sticky notes are used to support individual reflection and expression. These sticky notes are then collectively organized to determine values shared by the group members (see Figure 2). Member responses highlight priorities, interests, and commitments. Through discussion, the DAT determines common themes and articulates a shared vision. The articulated vision sometimes takes the form of a vision statement, but other times it is just a subset of values (single words or phrases, often).

Facilitators have implemented the ideal future activity with a number of variations (Ngai et al., in press). In all variants, participants are asked to envision their ideal version of something: for example, a student graduating from the program, the student community, or departmental governance. In the case of a student, follow-up prompts might include: What will they know? What kind of person would they be? What will they be able to do? What will they value? For a community-focused brainstorm, participants might be asked to consider experiences, interactions, feelings, relationships norms, and indicators: How would they know if it was achieved?

DAT facilitators use a variety of activities to move from vision to outcomes and ultimately to project activities. Facilitators keep the focus on outcomes by frequently directing the group to consider how their progress aligns with the values and/or vision they originally articulated. The particular techniques utilized by the facilitators depend on both the needs of the DAT and individual facilitation styles, so there is no single canon of activities that facilitators use (see Ngai et al., in press). Here, we illustrate a variety of different tools that have been used by DAT facilitators.

Methods

Data for this article were collected from a multi-institutional project focused on change in over a dozen STEM departments. Data include over 75 interviews with faculty members, thousands of pages of meeting minutes and facilitation/research journals, and artifacts collected from DATs. Here, we focus on a subset of the overall data corpus to describe experiences in five DATs. Of particular relevance are facilitation journals. These journals provided a summary of each meeting, a log of facilitation decisions and practices during the meeting, and a summary of a debrief conversation between the facilitators. Our practical experience working with DATs is also an important source of data for our case construction. All data below are de-identified.

Our analyses were guided by a case study methodology, used to explain a “contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context” (Yin, 2009, p. 18). Yet given length constraints, we do not consider the examples below to be formal case studies of the DATs but rather illustrative, extended examples that highlight the use of an outcome focus. Multiple cases illustrate the same phenomenon in different contexts. We draw from the three steps of the change cycle (see Figure 1) to describe the work of the DATs.

The descriptions of the DATs below have been drafted by various project members who were either directly or indirectly involved in facilitation (three were drafted by the first two authors, and one was drafted jointly by the fourth and fifth authors). These descriptions were then compared to meeting minutes and the extensive facilitator journals described above. Finally, other team members, and particularly the facilitators involved with each DAT, read the descriptions and edited as appropriate. This triangulation of data sources made it possible to reconstruct summaries of the DATs that were both accurate and highlighted particular facilitation strategies. This process of pattern matching, triangulating sources, and mitigating bias from our team was informed by Lincoln and Guba’s (1985) trustworthiness framework.

Results

Vignettes from five DATs are given to illustrate how they developed a shared vision and identified outcomes, planned activities, and implemented activities in their departments.

Herbs DAT: Improving Undergraduate Skills

The Herbs DAT included faculty members, one graduate student, and one undergraduate student.

Identifying Outcomes

The DAT began with a pre-visioning activity. Participants were given five minutes to individually write down their personal and professional aspirations and what they hoped others would get out of the DAT. This was followed with a popcorn-style discussion, during which individuals each shared their brainstorming. This divergent conversation elicited a variety of ideas before narrowing the focus. Participants described their aspirations around topics such as improved teaching, a more innovative curriculum, and changing departmental structures.

During the next meeting, participants were introduced to the importance of an outcome-focused approach and completed the ideal future activity with a focus on students in the undergraduate major. The values that came out of this activity focused on higher-order skills, professionalism, mentoring, and supporting students from a diversity of backgrounds. These general values were then consolidated into seven specific categories.

Planning

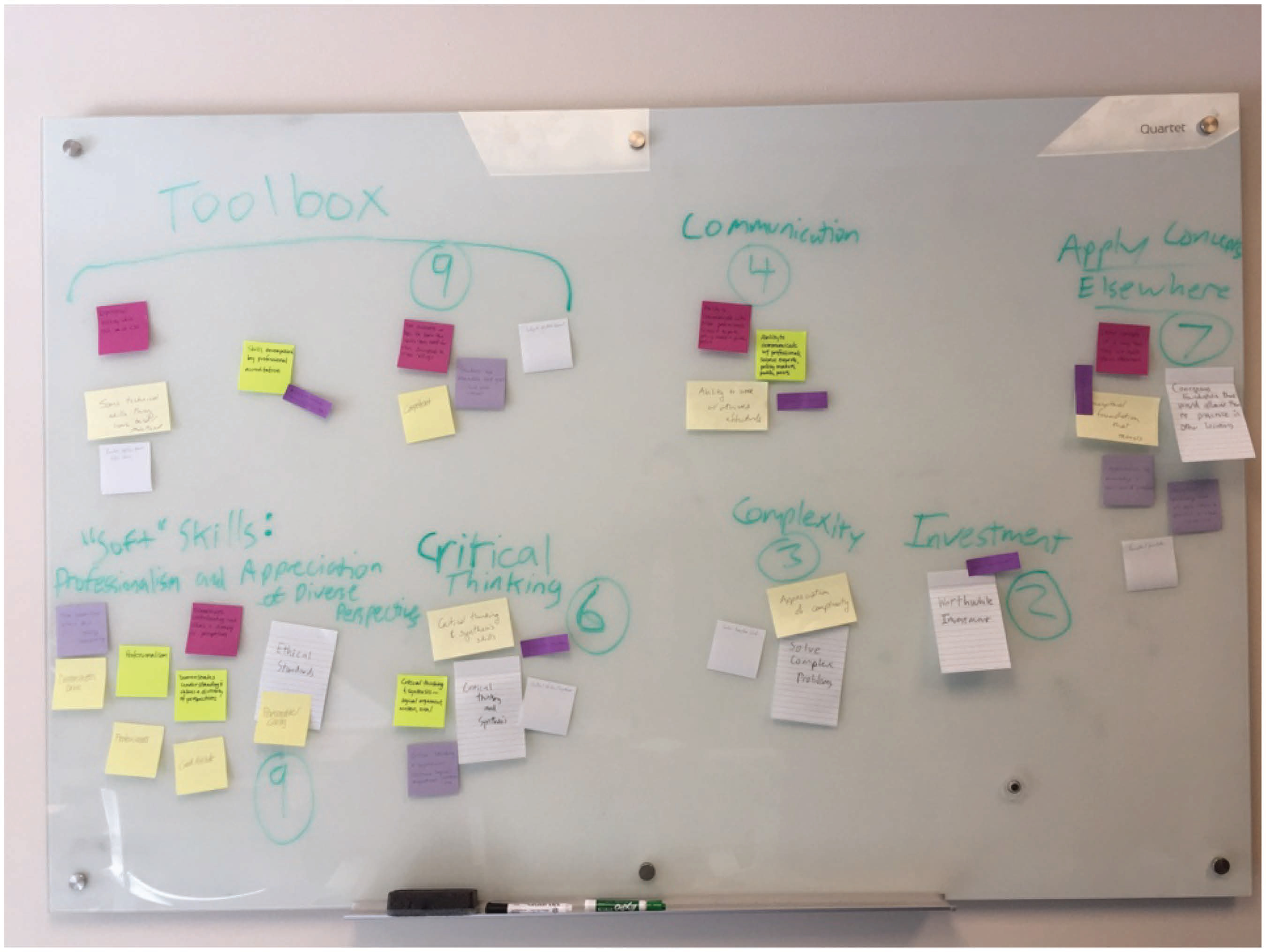

The DAT simultaneously identified desired outcomes while narrowing down previously proposed activities. There were a number of mutual areas of interest for the participants, so it was advantageous for them to consider their capacity to implement particular activities before narrowing on the outcome. Facilitators thus proposed that the group use a matrix to organize the ideas, in which each of the seven visioning values was given a column, and projects (activities) were organized along the rows (see Figure 3). DAT members decided to assign themselves homework to individually evaluate the fit of each proposed activity with the articulated values.

The evaluated matrix made it easy for DAT members to see how the proposed activities aligned with each category. This allowed the group to realize that the category of Higher Order Skills was aligned with the greatest number of projects. This process led the group to quickly decide to make the outcome of learning Higher Order Skills the focus of their DAT. From there, the group chose to focus on the project of creating an undergraduate skills assessment.

Implementation

Because of the deliberate visioning process, the DAT had a road map to guide its work toward building the skills assessment. After starting the development process, the DAT realized that to ensure the implementation of the assessment, it would need to create a department-wide assessment plan. Ultimately, the DAT presented the assessment plan to their department, gained their approval, and later presented their assessment pilot data. After two years, DAT external facilitation ended, and a faculty committee was established to fully implement the assessment plan. They expect to use skills assessment data on a long-term basis to guide improvement of skill-oriented teaching practices within the department. In this way, the deliberate process of the DAT set it up on a course toward continuous improvement. Without the guidance of the facilitators, the DAT members could have just as easily fallen into the trap of focusing on problems and may have believed that once an assessment was developed, the problem was now solved. For example, the facilitators intervened early on when a DAT member proposed piloting items without first eliciting faculty opinions, to ensure alignment of the skills assessment.

Summoning DAT: Improving Undergraduate Community

The Summoning DAT began with two tenure-track faculty, two non-tenure-track faculty, and two graduate students.

Identifying Outcomes

The Summoning DAT also began with a pre-visioning activity and then the ideal future activity, with a focus on undergraduate students. This process yielded four categories that described their vision of an ideal undergraduate student: knowledge, technical skills, intellectual skills (critical thinking), and being a team player. However, in discussing these general value categories, the DAT did not arrive at a clear vision of outcomes it wished to achieve. The DAT was very small at this point (two members and two facilitators), and the facilitators encouraged it to bring more members into DAT to achieve whatever goals it decided upon.

Rather than continuing its discussion at a theoretical level, the DAT consulted data to support the visioning process, because it had access to a number of existing surveys that had previously been administered to students about their experiences in the department. Looking at the data, there was a clear theme that students were struggling with a lack of community in the department. The DAT acted quickly to recruit two students who could help them better understand a student perspective.

Given the change in DAT membership, the facilitators encouraged the new group to again engage in a shared visioning process. Thus, the DAT decided to do a second version of the ideal future activity, this time focusing on the “ideal undergraduate community.” They decided that the main outcome they wanted to focus on was developing a sense of community among the undergraduates, because they had just established a new undergraduate major. The DAT presented their progress at a faculty meeting, which helped them recruit more members.

Planning

The following semester, the DAT reconvened with a total of eight members. The DAT brainstormed undergraduate community-strengthening projects. Each DAT member listed multiple outcomes and corresponding activities to build community. The facilitators consolidated these ideas into a matrix (Table 2). This supported DAT participants in deciding to pursue projects that increased communication to and among

Outcome-Activity Matrix

| Person | DAT Member 1 | DAT Member 2 | DAT Member 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Effective communication to undergraduate students | Create stewardship system for career, social, and vision development | Establish academic resources for Summoning majors |

| Activity | Survey the students to find out how they would like the department to communicate with them. | Identify potential career stewards in industry, academia, and government in the Boulder region, who work with students to further their career goals. | Organize tutoring hours in the lounge |

| Activity | Communication ideas: website, listservs, twitter, an app such as Slack, an Summoning app, etc. | Have activity 1 culminate into 1 career day where students, faculty, and stewards can “find each other”. Advertise internship and job opportunities (potentially also through internal website) during these events. | Use the website and listservs to effectively distribute opportunity announcements (newsletter?) |

| Activity | Newsletter or website spotlight | Entrain undergraduate students in social committee, which is currently mainly a graduate student activity, and promote connections between undergrads and graduate students. Perhaps also assign “graduate student and/or teaching/research faculty stewards” and for undergraduates (something like that is successfully done in schools, so why not in college as well). | undergraduates and projects that provided community-building experiences that also enhanced their professional skills. |

Implementation

Over the next two years, the DAT engaged undergraduate majors in a wide variety of activities related to the first two projects in Table 2, including establishing departmental social networks on Facebook and LinkedIn and offering a Fall Welcome event. They focused most of their energy on establishing an annual Industry Night that brings together undergraduates, graduate students, and alumni working in related area industries. Their work for this major event included gathering employer and student interest data during the planning process and feedback after the event. The DAT is now working independently and is facilitated by faculty members.

Pyromancy DAT: Improving Departmental Community

The Pyromancy DAT also focused on community building across the department. The Pyromancy DAT concluded its work after two years, and now a second spinoff DAT has been formed to attend to equity issues.

Identifying Outcomes

To begin, the facilitators explicitly contrasted outcome- and problem-oriented work to the participants and invited discussion. Then the DAT engaged in the ideal future activity, with the following prompt: “What are the characteristics of an ideal Pyromancy department community? Consider things such as: experiences, interactions, feelings, relationships, norms, and indicators: how would you know an ideal community is working?” The group generated six values categories, which included open and honest communication, diversity and inclusion, improved teaching, and expanded research opportunities. They then narrowed this down to a specific vision-based outcome: strengthening their community by improving communication between departmental groups.

Guided by facilitators, DAT members listed a large number of possible specific outcomes and projects that they might aim to achieve related to the vision categories in a spreadsheet. To prioritize among outcomes, facilitators used the 25/10 crowd sourcing activity (Liberating Structures, 2020). The activity that they settled on was organizing a Departmental Forum for all department members as a first step toward the outcome of improving communication in the department.

Planning

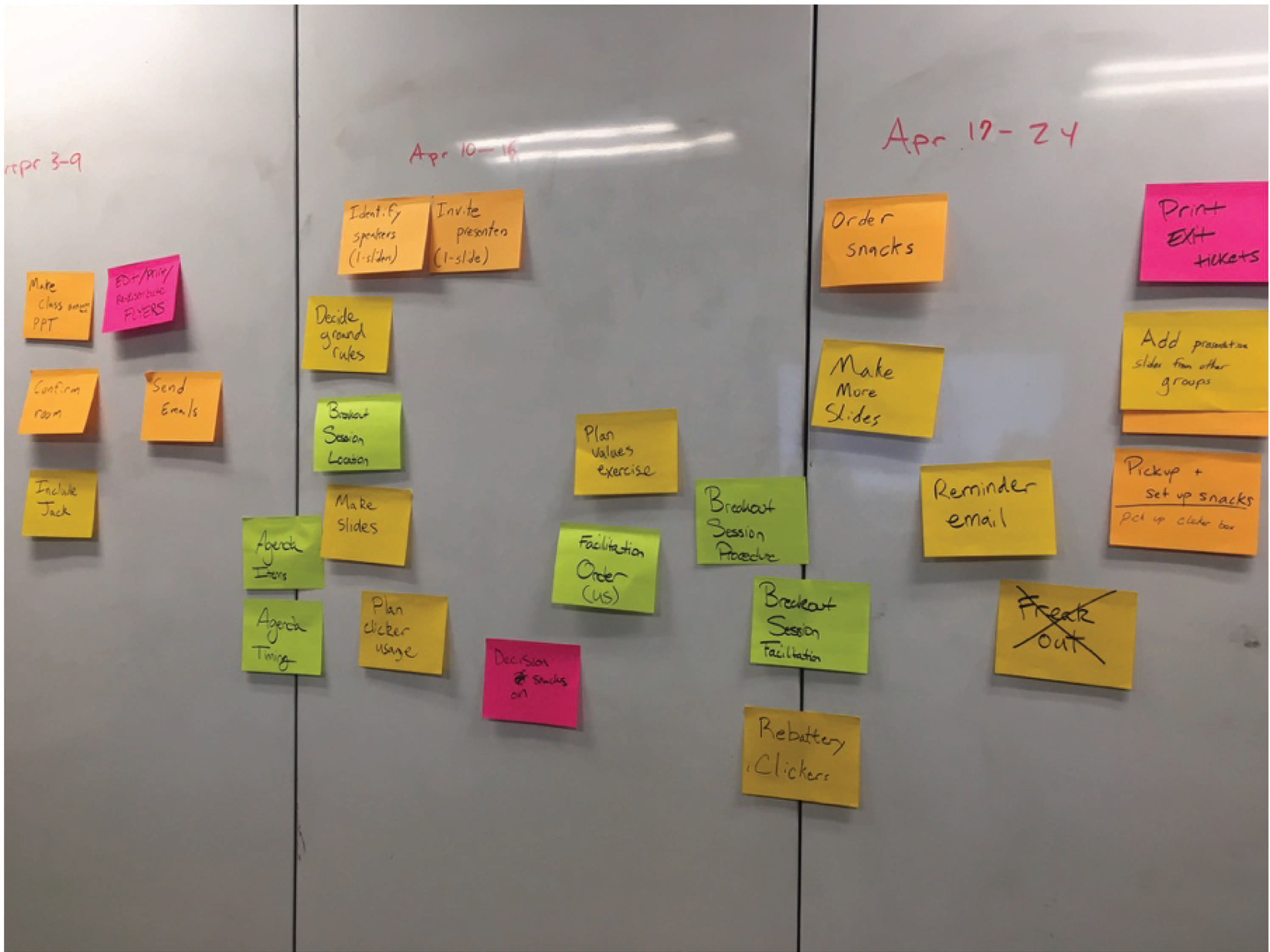

Next, the group listed specific activities associated with planning the Departmental Forum. This included agenda development and outreach to all departmental groups. Two subgroups were created to complete these two major activities. The DAT created a visual timeline to ensure completion of all activities (see Figure 4). As the Departmental Forum was built around communication, the DAT members planned activities much like those used in the DAT itself, including the ideal futures activity.

Implementation

Like the Summoning DAT, the Pyromancy DAT collected feedback from participants who attended the Departmental Forum. It used this feedback and its own reflections to guide its choices of communication-related activities in their second year of work, which focused on a departmental Fall Welcome event, supporting all departmental committees in adopting collaboratively determined standards and norms of communication, improving website communications, making departmental operations more transparent and accessible to students, and planning the second annual Departmental Forum. These improvements continue to be sustained.

Divination DAT: A Focus on Learning Outcomes and Assessment

The Divination DAT was composed of three staff members, two tenure-track faculty members, one graduate student, one undergraduate student, and the department chair. The impetus for the DAT to be formed was pressure to maintain accreditation for the divination program.

Identifying Outcomes

The DAT began by developing a vision for what it wanted its students to achieve. This vision would provide the basis for developing student learning outcomes (SLOs) to support the accreditation process. Thus, the DAT facilitators initiated a two-part visioning process, asking DAT members to first reflect on the prompt “What are the anticipated gains for this DAT?” Facilitators initially categorized responses based on needs related to individual, student, departmental, team and process, and research and presented these results at the start of the second meeting.

The second part of the visioning process prompted DAT members to reflect on what they envisioned as the ideal student leaving the divination program after four years. Responses were then transferred to sticky notes and a set of common themes created (see Figure 5). Facilitators supported DAT members tying back to these themes by anchoring planned programmatic assessment work to the vision of the DAT and of the ideal student. For example, DAT members would reference their list of ideal student characteristics when examining courses, asking “Does this capture what we want to assess in an ideal student?” or if they were identifying which ideal student characteristics presented under existing SLOs.

Planning

The DAT next determined what would be needed to establish updated SLOs. Right from the start, the facilitators realized that the DAT members needed time to develop a common understanding of the issues related to establishing SLOs. Thus, the fall semester was spent examining data gathered from a departmental survey, existing SLOs, and current required coursework for students in the program. This information supported DAT members in developing revised SLOs. Gathered data and information allowed for DAT members to assess whether or not courses were accurately capturing the revised SLOs as well as if the SLOs were aligned with the ideal student, tying their work to the desired vision.

Implementation

Moving forward, the DAT began developing an assessment plan that better reflected their SLOs. This involved identifying components of the program that either could be used or were already being used to assess SLOs. Facilitators supported this focus on the outcome of assessment using SLOs by structuring multiple DAT meetings around a matrix that identified the intersections between SLOs and program courses. Furthermore, some SLOs were revised if characteristics or outcomes were not being adequately represented. Artifacts from their visioning activity provided guidance in their work. For example, communication was identified as a desired skill (Figure 5) for students graduating from their program; however, as one DAT member stated, “We don’t have oral and written communication in our SLOs and this is a glaring omission.” In addition, after establishing a particular SLO, another DAT member reflected, “This makes us think about our SLOs and if that’s what we really want. They’re nice and I can see where they come from, but going through all this makes me go back to the outcomes.”

After two years the Divination DAT graduated from external facilitation. To support this graduation process, two DAT members shadowed the DAT facilitators to apprentice in their facilitation techniques. However, they continue to meet and engage as a DAT. The group is currently testing assignments and rubrics tied to their updated SLOs. The rubrics and SLOs are sustainable mechanisms that will allow Divination to continue to collect data, revise their teaching, and improve their students’ learning over years to come.

Sorcery: Falling Into the Trap of Problem-Solving Mode

The Sorcery DAT was formed after the DAT project team met with the department chair and the associate chair for undergraduate studies, the latter of whom was responsible for bringing together the DAT. These initial conversations revealed that the department had already successfully revised its introductory courses and wanted to do the same for upper-division courses. Like in Divination, DAT members were appointed. The DAT members were chosen by the undergraduate studies chair (who also participated) to include individuals who were interested in education and also those who were involved in teaching the upper-division courses.

Identifying Outcomes

The DAT began with the ideal student activity to brainstorm values for students graduating from the program. This activity was met with skepticism from one of the DAT members, who ultimately left the DAT after two meetings. This participant questioned the utility of starting from values and went on to describe what he felt was the needed solution. The facilitators redirected participants to complete the activity, and the DAT members generated the following list of values: communication, problem-solving, problem posing, rigor, self-assessment, risk-taking, content knowledge, and appreciation of the discipline’s beauty. Unfortunately, despite the efforts of the facilitators, the DAT maintained a problem-solving focus rather than an outcome focus throughout their work.

Planning

The DAT was quick to move to goals without fully establishing its vision. As was determined before the DAT convened, the goal was to complete the DAT’s work with a specific proposal for how to revise the upper-division course sequence. To support this goal, the DAT analyzed institutional data to better understand student course-taking patterns. This analysis revealed that the order in which students took the upper-division courses had a significant relationship to their overall scores in the courses. The DAT shared its results with the department and proposed three changes: (1) revising the prerequisite feeder course, (2) changing and enforcing the prerequisite order for upper-division courses, and (3) creating a major and non-major version to better support students in the major. These proposals were intended to be the solutions to the problem the DAT was working on. After making this proposal to the department, the DAT disbanded after one semester.

Implementation

Personal communication with the department chair years after the DAT disbanded revealed that he was satisfied with the proposal that the DAT came up with (i.e., he viewed the DAT as a success). Yet it was unclear to what extent the course proposals had actually impacted instruction in the department in a deep way, given the resistance of some department members to change. From our view, this DAT proceeded quickly with a problem-solving focus, which may have contributed to the lack of capacity for making sustained changes based on the DAT’s proposal. Because the DAT was formed with a clear set of actions in mind (to solve a problem), the DAT served mostly as a space for data analysis and making a proposal to the department.

Discussion and Implications for STEM Education

Many different kinds of changes can be facilitated in undergraduate STEM education when groups focus on positive outcomes rather than on individual problems. In the context of DATs, nearly every group we have worked with has succeeded in developing an outcome focus and building sustainable, structural improvements within their department that serve their common goal (Reinholz, Ngai et al., 2019). Four of the five DATs described above made considerable progress toward building lasting structures that would continue to support ongoing departmental improvement. The fifth, in contrast, was impeded by its focus on solving problems.

A focus on outcomes allows departments to look at their programs more holistically rather than focusing on a single “problem” so that lasting, meaningful change can take place. It allows for a departmental group to build on strengths and assets as they work toward their shared goal. The work described above provides a useful starting point for others who would like to work with departmental groups to improve undergraduate STEM education. Here, we highlight a number of lessons learned and implications for practice.

First, in our experience, DATs that strongly adopt and follow their vision are more likely to stay focused and achieve positive outcomes, compared to DATs that need to be reminded of the vision and who may have more difficulty staying focused. Consider the Summoning DAT, which had shifts in attendance and multiple visioning activities. While the DAT ultimately did make progress toward its shared vision, the path was less straightforward and required ongoing guidance and intervention from the facilitators to help promote decision-making. In other DATs, like Herbs and Divination, once the vision was set, there was a fairly linear path moving from vision to outcomes and activities. Particularly in the Divination DAT, the visioning exercises guided much of the thinking about student learning outcomes and curricular alignment of their program. We suspect that these tendencies to lose focus or temporarily slip into a problem-solving mode depend on both the individuals in the DAT and the culture of the specific discipline. As we saw in Sorcery, this was a department that had already had prior success in course revisions and thus carried a problem-solving orientation to the DAT process.

Second, given the challenges of developing and staying focused on a vision, facilitators need to utilize a variety of strategies. There is no one-size-fits-all. How this process develops depends on the particular context and facilitators involved in the work. At times, it was sufficient for facilitators to simply remind participants about the vision to stay on track. For example, with Divination, when members were discussing how components of their program connected to the SLOs, facilitators only needed to participate in the conversation, stating, “Technically they should align, they should end up as part of that ideal student.” In other cases, it was necessary to use specific activities to help refocus the DAT to stay attuned to its desired outcomes.

Third, we found the use of visuals, sticky notes, and other artifacts to be important mediators for productive visioning conversations. By introducing activities that disrupt the typical flow of whole-group conversations, we were able to help participants think in new ways rather than defaulting to the problem-solving mode that is prevalent in traditional departmental committees. In addition, opportunities for individual think time (e.g., writing on sticky notes) and distributed group discussion (e.g., moving sticky notes around, creating themes of sticky notes) helped flatten out hierarchies and created more space for all members to contribute meaningfully. Lastly, these activities produced visuals that facilitators frequently turned DAT attention to in subsequent meetings, which proved to be powerful reminders. Although these visuals were generated in person, they can also be implemented virtually by using online collaborative workspaces.

Regardless of the kind of visioning exercise used, the resulting outcomes provided an anchor for DATs as they began their work. We do not claim that an outcomes focus is sufficient for change in undergraduate STEM education. However, we highlight its utility, as a focus on achieving collective positive outcomes has played a key role in DATs’ progress toward and success in implementing meaningful and lasting change (Reinholz et al., 2018; Reinholz, Pilgrim et al., 2019). Given the flexibility of this approach, it is highly likely that it could be adopted effectively by a wide variety of project teams in different contexts.

Biographies

Daniel L. Reinholz is an Associate Professor of Mathematics Education at San Diego State University. Broadly speaking, Dr. Reinholz’s research focuses on creating tools for educational transformation, to improve equity and mitigate systemic oppression. Their research is primarily situated within three interrelated areas: disability justice, racial and gender equity, and systemic change.

Mary E. Pilgrim is an Associate Professor of Mathematics Education at San Diego State University. Her research area is in undergraduate mathematics education with a focus on course design, pedagogy, professional development, and systemic change. Through combined lenses of equity and sustainability, Dr. Pilgrim’s research and scholarly activities connect the use of evidence-based practices to the professional development of graduate student instructors.

Amelia Stone-Johnstone is an Assistant Professor of Mathematics Education at California State University, Fullerton. Her research interest is on students’ experiences in gateway mathematics courses at postsecondary institutions. She is interested in systemic change toward equitable instructional environments and studies how opportunities to contribute to classroom discourse are dispersed by social markers (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity). In addition, she has worked on projects focused on the implementation of active learning strategies.

Karen Falkenberg is a member of The Institute for Learning and Teaching (TILT) Senior Leadership team at Colorado State University, acting as the Director of Curriculum and Instruction and leading a group of instructional designers and educational researchers. Falkenberg has over 37 years of experience in STEM and education, beginning with her work as a research chemical engineer.

Christopher Geanious is an Instructional Designer at Colorado State University. His work and interests involve all aspects of teaching and learning in higher education with emphasis on multimodal teaching technologies/strategies and 3D visualization and design pedagogies. Most recently, Chris has been a leader in the cross-campus response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the areas of faculty development/preparedness and educational technologies.

Courtney Ngai (she/her/hers) is a Research Scientist within The Institute for Learning and Teaching (TILT) at Colorado State University and a consultant for Empowered Consulting. Dr. Ngai’s current work focuses on organizational change at higher institutions as part of the Departmental Action Team project. She has facilitated departmental teams working to improve their undergraduate programs and is investigating how to best support and sustain change in higher education.

Joel C. Corbo is a Senior Research Associate in the Center for STEM Learning at the University of Colorado Boulder. His work focuses on implementing and studying mechanisms to improve education in university departments, with a focus on organizational and cultural change. He also co-leads the Access Network, a national network of student-centered equity programs working toward a more just, equitable, and humane academic STEM culture.

Sarah B. Wise is on the research faculty at the Center for STEM Learning, University of Colorado Boulder. Her interests include best practices in instruction and facilitation, effective and equitable change in academia, and the development of change agents. With the Departmental Action Team project, she is investigating long-term impacts of teams that are working independently to make sustainable change in their departments.

Funding Information

National Science Foundation award number #1626565

References

Argyris, C. (1992). On organizational learning (2nd ed.). Blackwell Publishers.

Cooperrider, D., Whitney, D., & Stavros, J. M. (2008). The appreciative inquiry handbook: For leaders of change. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

de Shazer, S., & Dolan, Y. (2012). More than miracles: The state of the art of solution-focused brief therapy. Routledge.

Elrod, S., & Kezar, A. (2015). Increasing student success in STEM: A guide to systemic institutional change. A Keck/PKAL Project at the Association of American Colleges & Universities.

Fritz, R. (1989). The path of least resistance: Learning to become the creative force in your own life. Fawcett Books.

Garmston, R. J., & Wellman, B. M. (2016). The adaptive school: A sourcebook for developing collaborative groups (3rd ed.). Rowman & Littlefield.

Henderson, C., Beach, A., & Finkelstein, N. (2011). Facilitating change in undergraduate STEM instructional practices: An analytic review of the literature. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 48(8), 952–984.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kezar, A. (2011). What is the best way to achieve broader reach of improved practices in higher education? Innovative Higher Education, 36(4), 235– 247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-011-9174-zhttps://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-011-9174-z

Kezar, A. (2014). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change. Routledge.

Kim, J. S. (2008). Examining the effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy: A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507307807https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507307807

Liberating Structures. (2020). 25/10 crowd sourcing. http://www.liberatingstructures.com/12-2510-crowd-sourcing/http://www.liberatingstructures.com/12-2510-crowd-sourcing/

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications.

Lucas, J. R. (1998). Anatomy of a vision statement. Management Review, 87(2), 22–26.

Maslow, A. H. (1966). The psychology of science. Harper and Row.

Ngai, C., Corbo, J. C., Falkenberg, K., Geanious, C., Pawlak, A., Pilgrim, M. E., Quan, G. M., Reinholz, D. L., Smith, C., & Wise, S. B. (2020). Facilitating change in higher education: The Departmental Action Team model. Glitter Canyon Press.

Ngai, C., Pilgrim, M. E., Corbo, J. C., Falkenberg, K., Geanious, C., Reinholz, D. L., Smith, C. E., Stone-Johnstone, A., & Wise, S. (In press). Guiding principles for change in undergraduate education: An analysis of a departmental team’s change effort.

Oswald, M. E., & Grosjean, S. (2004). Confirmation bias. In Pohl, R. F. (Ed.), Cognitive illusions: A handbook on fallacies and biases in thinking, judgement and memory (pp. 79–96). Psychology Press.

Quan, G. M., Corbo, J. C., Finkelstein, N. D., Pawlak, A., Falkenberg, K., Geanious, C., Ngai, C., Smith, C., Wise, S., Pilgrim, M. E., & Reinholz, D. L. (2019). Designing for institutional transformation: Six principles for department-level interventions. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 15(1), Article 010141. https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.15.010141https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.15.010141

Reinholz, D. L., Corbo, J. C., Dancy, M., & Finkelstein, N. (2017). Departmental Action Teams: Supporting faculty learning through departmental change. Learning Communities Journal, 9, 5–32.

Reinholz, D. L., Matz, R. L., Cole, R., & Apkarian, N. (2019). STEM is not a monolith: A preliminary analysis of variations in STEM disciplinary cultures and implications for change. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 18(4), mr4. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-02-0038https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-02-0038

Reinholz, D. L., Ngai, C., Quan, G., Pilgrim, M. E., Corbo, J. C., & Finkelstein, N. (2019). Fostering sustainable improvements in science education: An analysis through four frames. Science Education, 103(5), 1125–1150. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21526https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21526

Reinholz, D. L., Pilgrim, M. E., Corbo, J. C., & Finkelstein, N. (2019). Transforming undergraduate education from the middle out with Departmental Action Teams. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 51(5), 64–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2019.1652078https://doi.org/10.1080/00091383.2019.1652078

Reinholz, D. L., Pilgrim, M. E., Falkenberg, K., Ngai, C., Quan, G., Wise, S., Geanious, C., Corbo, J. C., & Finkelstein, N. (2018). Departmental Action Teams: A five-year update on a model for sustainable change. The RC20/20 Project: A digital publication of the Reinvention Collaborative. https://www.rc-2020.org/s/Falkenberg-et-al-DAT.pdfhttps://www.rc-2020.org/s/Falkenberg-et-al-DAT.pdf

Reinholz, D. L., Rasmussen, C., & Nardi, E. (2020). Time for (research on) change in mathematics departments. International Journal of Research in Undergraduate Mathematics Education, 6(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40753-020-00116-7https://doi.org/10.1007/s40753-020-00116-7

Ross, L. (1977). The intuitive psychologist and his shortcomings: Distortions in the attribution process. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 10, pp. 173–220). Academic Press.

Senge, P. M. (2006). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Random House.

Smith, J., diSessa, A. A., & Roschelle, J. (1993–1994). Misconceptions reconceived: A constructivist analysis of knowledge in transition. Journal of the Learning Sciences, 3(2), 115–163. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0302_1https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327809jls0302_1

Taylor, A. L., & Karr, S. (1999). Strategic planning approaches used to respond to issues confronting research universities. Innovative Higher Education, 23(3), 221–234. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022998518559https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022998518559

Wasserman, D. L. (2010). Using a systems orientation and foundational theory to enhance theory-driven human service program evaluations. Evaluation and Program Planning, 33(2), 67–80.

Yin, R. K. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods (Vol. 5). Sage Publications.