Communities of practice (CoPs) are composed of voluntary members who share a common interest in co-creating and sharing knowledge to collectively solve a specific problem (Wenger, 1998; Wenger et al., 2002). At the same time, members support one another’s developing expertise and foster the transfer of knowledge across the membership and into the collective, aligning with a diffusion of innovation change theory (Argote & Ingram, 2000; Rogers, 2003; Wenger, 1998). Practitioners in educational development (ED) might apply the CoP approach to achieve a product or organizational outcome by distributing work across skilled members representing a diversity of perspectives and approaches (Hoffmann et al., 2021; Korsnack & Ortquist-Ahrens, 2021). The field of ED is an ideal context for CoPs, since ED CoPs share three elements with CoPs more generally: domain, practice, and community (Wenger, 2001; Wenger et al., 2002; Wenger & Snyder, 2000). Domain is the shared interest of the community, such as the support of a specific group of instructors in the acquisition of particular pedagogical skills. Practice is the communally developed set of resources in support of that domain, such as a workshop, a print or web guide, or an instructional video. The third element of a CoP, community, reflects how the members engage with one another and create a sense of commitment and reciprocity.

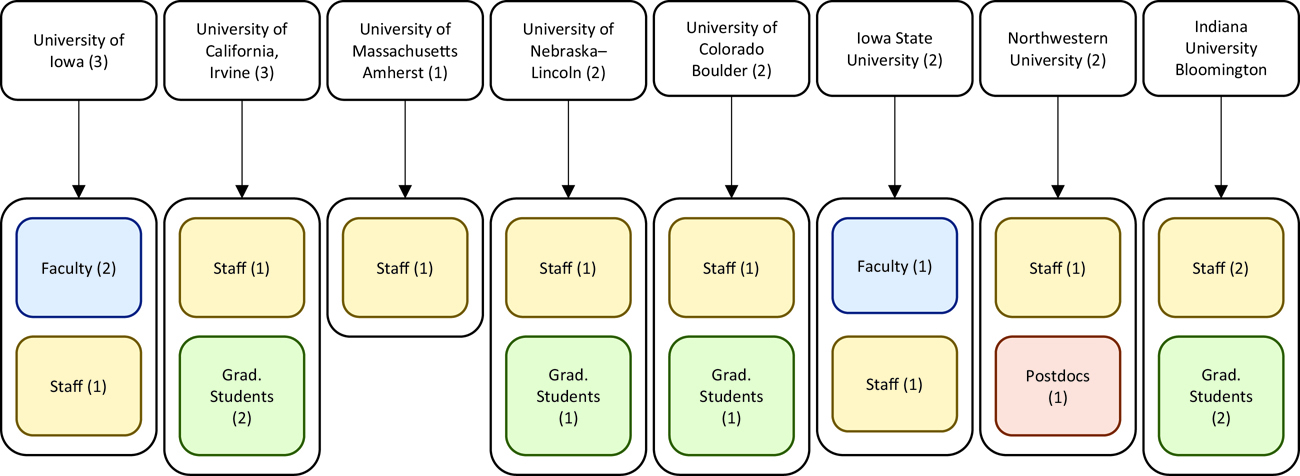

Here we present a description of community aspects of a CoP that emerged among educational developers. They served as facilitators of an across-institutional, hybrid, seven-week workshop series on course design for graduate students and postdoctoral scholars, Transforming Your Research Into Teaching (TYRIT) (Hoffmann et al., 2021). With 19 facilitators (including the five authors of this study) across eight institutions, members represented various professional roles and career stages. There are features of this CoP that provide opportunities to elaborate on our understanding of CoPs: (1) a high level of community engagement within facilitator interactions, (2) the practice of educational developers working in community, (3) the context of teaching graduate students fundamentals of course design, and (4) the wide geographic distribution of facilitators from many different institutions.

The aim of this study is to explore the experience of community for this group of facilitators. Because a CoP creates a resource in support of an outcome, assessments typically focus on whether a CoP resulted in organizational improvements (Hoyert & O’Dell, 2019; Jimenez-Silva & Olson, 2012). Thus, these assessments might miss outcomes that happen within the community interaction space while doing the domain-practice work. For example, previous literature has described this workshop series (practice) and its impact on the pedagogical knowledge and skills of participating graduate students and postdoctoral scholars (domain) (Hoffmann et al., 2021; Hoffmann & Lenoch, 2013).

CoPs are sites of important mentorship and networking experiences that support professional development for educational developers (Donnell et al., 2018; Drane et al., 2019; Lave & Wenger, 1991). Because the majority of ED practitioners are trained in an academic discipline other than education (POD Network, 2016), CoPs in ED reach beyond formal structures (e.g., classrooms) to connect people from different disciplines within the field of ED (Kapucu, 2012; Teeter et al., 2011).

This CoP created programming to support the development of graduate students and postdoctoral scholars (Austin & McDaniels, 2006; Border & von Hoene, 2010; Lovitts, 2001, 2004; Nerad et al., 2004; Nyquist et al., 2004; Wulff et al., 2004). The resulting program particularly focused on the skills of course design, using an approach similar in format to multi-session course design institutes that are common in faculty development (Hoffmann et al., 2021; Palmer et al., 2016). These institutes are high engagement for participants (Palmer, 2011) and, by implication, high intensity labor for developers. Thus, collaboration around this work is an opportunity for graduate student, postdoctoral, and faculty developers to work together on a major project, when many are often professionally isolated in small teams or working alone at their institutions (Chen et al., 2022).

The broader across-institution network of facilitators making up the CoP consisted of subgroups of facilitators from the same local institution. Existing research largely investigates the impact of collaboration in CoPs purely in the context of single institutions (Hadar & Brody, 2018; Margolin, 2011), or purely in an across-institutional context (Bouchamma et al., 2018; Gehrke & Kezar, 2017; Guberman et al., 2021; Kirkman et al., 2011; Soekijad et al., 2004). Some research examines the differences in outcomes between CoPs of different scope. For example, Vincent et al. (2018) discuss the effectiveness of intradisciplinary vs. transdisciplinary CoPs and offer a perspective on the formation of each kind of CoP. Elsewhere, Webber and Dunbar (2020) argue that communities of practice are fractally structured, and organizational differences are required between CoPs of different sizes to ensure that those CoPs function successfully. However, relatively little attention has been paid to the importance of sustaining factors between CoPs, where different kinds of CoPs coexist within the same overall structure. Thus, our CoP is an informative context for studying the community aspect of CoPs in ED and how across-institutional communities function to reap benefits, bridge challenges, and meet the needs of members.

We wanted to understand the meaning and value facilitators place in their participation in our TYRIT CoP. We used qualitative items from a survey to explore these overarching questions and specific research questions:

How do members experience the community aspect of our CoP?

What are CoP members’ experiences of productivity/effectiveness?

What are CoP members’ experiences of personal fulfillment/satisfaction?

What is the value of the across-institutional aspect of our CoP in sustaining our CoP?

What are CoP members’ experiences in within-institution communities?

What are CoP members’ experiences in across-institutional communities?

What value differences did CoP members perceive between their participation in within-institution communities and their participation in across-institution communities?

Methods

Description of Program

As described previously, TYRIT is a seven-week serial workshop program on course design for graduate students and postdoctoral scholars (Hoffmann et al., 2021). The program supports participants as they develop course proposal materials for an academic job interview, for a course they are planning to teach, or for a course they are competitively applying to teach. TYRIT is a multi-institutional program, drawing participants from research institutions across the United States, with its administrative home within the Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching, and Learning (CIRTL) Network. The hybrid design of TYRIT follows principles of flipped pedagogy (Abeysekera & Dawson, 2015). The workshop series provides online, asynchronous content on course design and live, synchronous meetings with local learning communities (LLCs) at each participating institution. LLCs are led by teams of facilitators—educational developers who work for and with centers for teaching and learning—at each institution. Throughout the program, participants develop a course design project on their own and explore the topics and their course design experiences with peers in their LLCs.

TYRIT is similar in curriculum to multi-session course design institutes (Hoffmann et al., 2021; Palmer et al., 2016). TYRIT attends to the pedagogical training needs of graduate students and postdocs as well as their developmental and professional contexts as aspiring future faculty (Austin & McDaniels, 2006; Border & von Hoene, 2010). By delivering the hybrid format course design institute through the multi-institution collaborative of CIRTL, TYRIT is a scalable model that fosters across-institution sharing and community building among hundreds of participants and many facilitators.

Roles and Activities in the TYRIT Facilitator Network

All facilitators of the TYRIT program, as educational developers, were past or are current members of the CIRTL Network, with the CIRTL Network acting as a facilitating mechanism for the CoP. The leaders of the CoP did not facilitate the group using empirically researched practices for team management (Bang & Midelfart, 2017; Kozlowski & Ilgen, 2006) or community-building research (Wenger, 1998; Wenger et al., 2002). Instead, their leadership styles were grounded in trauma-informed (Imad, 2021) and anti-oppression/liberation principles (e.g., Freire, 1968/2000; hooks, 1994). Their interpretations of these philosophical principles resulted in the following practices to ensure that members felt:

intellectually and emotionally resourced to lead their LLC;

encouraged to adapt, innovate, and share weekly activities for their LLC;

comfortable asking for what they needed and giving what they could in an environment of reciprocity and mutuality;

that their experiences and ideas mattered to the decision making;

that they could take leadership roles on projects within the TYRIT program;

a sense of belonging to the CoP; and

respected and validated within the CoP.

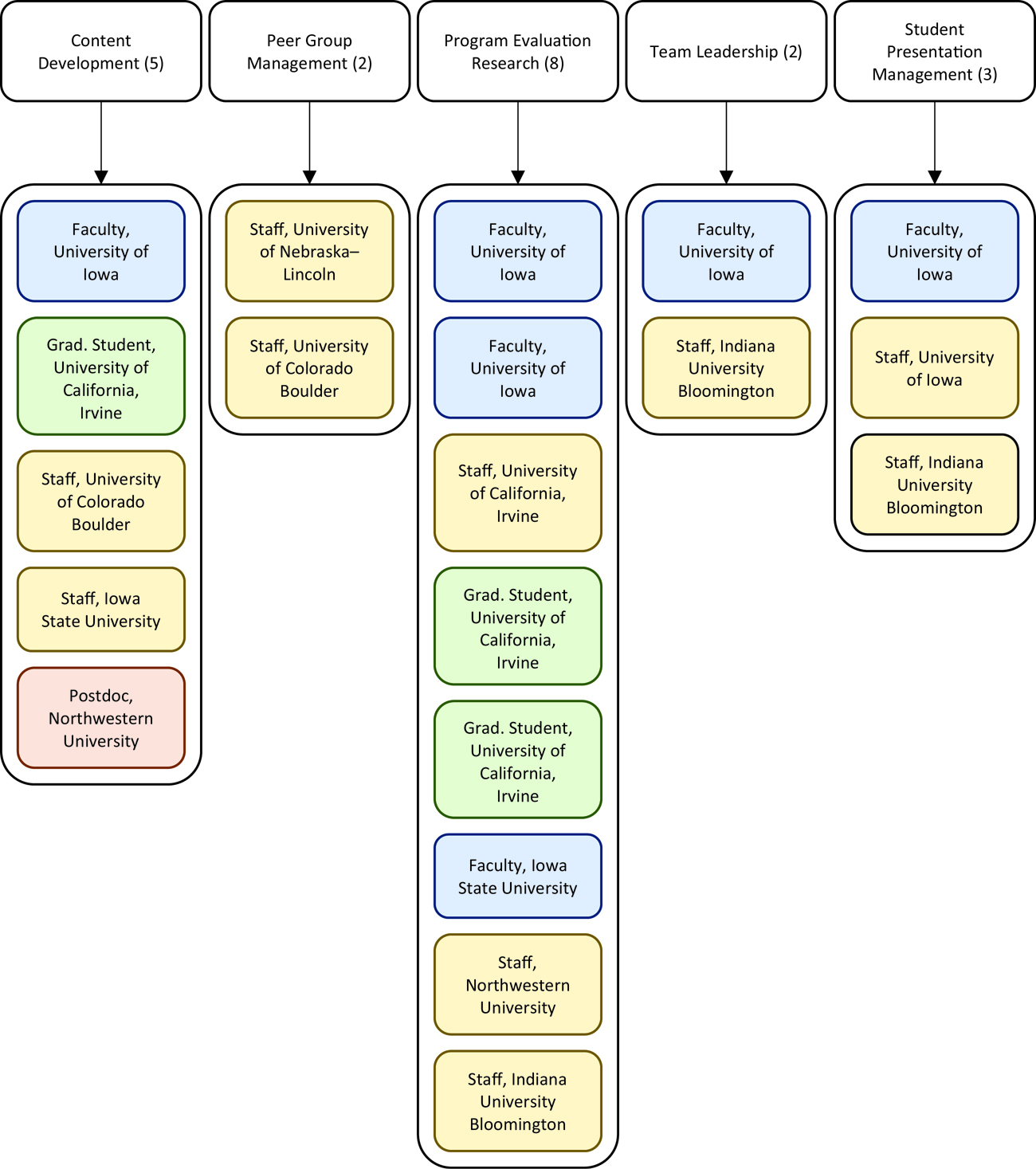

In TYRIT facilitator network meetings, members were presented with a menu of across-institutional working groups they might contribute to, and members volunteered to support groups in several ways based on their personal interests and availability (Figure 1B):

design and develop new asynchronous content materials;

share lesson plans for facilitating synchronous LLCs;

attend to workshop management tasks such as advertising, recruitment, matching students into groups, and project completion; and

contribute to educational research projects about the program.

Note. Organization of the 19 members of the TYRIT CoP is broken down by within-institution groups. The eight participating institutions are indicated in the top row. Within each of the eight institutions, groups of one to four team members collaborated to develop and manage their weekly LLCs. The columns below give a breakdown by role of facilitators at each institution. Numbers of individuals in each category are indicated in parentheses.

Note. Organization of the 19 members of the TYRIT CoP is broken down by across-institution groups. The top row indicates the five across-institutional groups. The columns below give a breakdown by role of facilitators in each across-institutional group.

Because the facilitator network was composed of a group of educational developers whose roles ranged from student to staff to faculty, each working group often had a mixed composition, bringing diverse perspectives to each project within the group. This also enabled across-institutional mentorship of graduate students by educational developers of different ranks. These working groups set up their own meeting schedules to manage various components of the course. Exchange of ideas occurred during synchronous online meetings and through an online repository that facilitators contributed to asynchronously throughout the course. The repository was a place where facilitators could share their plans, describe the outcomes of their meetings, and reflect on what worked best.

Study Population and Ethics Procedures

The study population was composed of the facilitators in this program, all educational developers, who came from the eight partner institutions in TYRIT. All 19 members of the facilitator network (including the five authors of this study) were eligible to participate in the study, and there were no exclusion criteria. Of these facilitators, 14 participated in the study (74% response rate). This study was approved as exempt by the University of Iowa Institutional Review Board (IRB#202007416).

To protect confidentiality of survey respondents, no questions were included that would identify study subjects, and participants were allowed to skip any questions they preferred not to answer. The survey was distributed anonymously to facilitators and results are presented in aggregate. Quotations are presented in this article with no associated identifying information. For the purposes of data presentation, all participants were assigned an arbitrary number that applied to their responses across the survey data set. This allowed for attachment of an ID number to all representative quotations to ensure that the data displayed in this article represent the range of survey respondents and so that no particular voice overwhelms the narrative. Where quotations are included, the associated ID number is of the form (Qn, #m), where n is the question number, and m is the arbitrary respondent number.

Survey Methodology

We used qualitative results from a survey to understand the commonality of experiences of TYRIT facilitators in their contributions to within-institution groups and across-institution groups (Creswell & Poth, 2016; Grossoehme, 2014; Webb & Welsh, 2019). We wanted to know what the experiences meant to facilitators, what factors were important in those experiences, and what impacts those factors had on them. The research team developed the survey de novo (see the Appendix) to describe and compare facilitator experiences in within-institution teams and in the across-institution activities. The survey was developed iteratively by the team and reviewed by a non-team member to ensure face validity. The survey consisted of 18 questions divided into four sections. In the first section, participants responded to four closed-response items that helped to define their institutional rank and role within their institutional facilitation team. In the second section, participants responded to five (two closed-response, three open-response) items related to their within-institution team dynamics and experiences. In the third section, participants responded to the same five questions, this time related to their experiences in across-institution team interactions. Finally, in the fourth section, four concluding open-response items asked participants to reflect on what they learned and how their experiences impacted their professional development. For the purposes of this study, we focused analysis on the open-response items in parts B and C (see the Appendix), as these items most directly addressed the research questions, and the small sample size limited the value of data from the closed-response items.

The survey instruments were developed between Summer 2019 and Summer 2020, and the program described in this study took place during Summer 2020. Thus, this work was at least in part done during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. We acknowledge that these extraordinary circumstances surely impacted the experiences of the facilitators on the team; therefore, we include mentions of the pandemic wherever they naturally occurred in the data. However, neither the impact nor context of the pandemic is a core focus of this study.

Data Analysis

The authors separated items related to within-institution teams and across-institution teams into two data sets. These free response items were grouped into clusters by two reviewers each, and open coding was used to establish themes for each item. Consensus was established within each dyad. Then each dyad presented their results to the other dyad to allow for comparison of themes between the within-institution and across-institution groups. This allowed for identification of themes that were especially prominent in one group but not the other. In particular, items related to effectiveness/productiveness were directly compared across groups, as were items related to personal satisfaction/fulfillment. All team members collaborated to identify themes within the responses to those items. The summary themes identified from these data were related to the three elements of CoPs (domain, practice, community) to evaluate how those elements were realized in different configurations of facilitator network members. Representative quotations are provided in the results as examples.

Results

The primary results of this study are captured in responses to four survey questions: (1) What did you find most effective or productive about collaborating with facilitators within your institution? (2) What did you find most effective or productive about collaborating with facilitators across different institutions? (3) What did you find most satisfying or personally fulfilling about collaborating with facilitators within your institution? and (4) What did you find most satisfying or personally fulfilling about collaborating with facilitators across different institutions? Themes that emerged in facilitators’ experiences are summarized in Table 1, and representative quotations for each theme are highlighted in Tables 2 and 3.

Themes Among Facilitator Experiences

Source of experience |

Community perspective |

|

|---|---|---|

Within institution |

Across institution |

|

|

Effective/ productive interactions |

|

|

|

Satisfying/ personally fulfilling interactions |

|

|

Note. Each theme is tagged with its associated domain(s) of a CoP: D = Domain, P = Practice, C = Community.

Themes in Tables 1, 2, and 3 are indexed according to one or more aspects of a CoP. D (“Domain”) indicates themes that refer to the topic/concept of TYRIT: for example, teaching backward course design to graduate students and how to lead learning communities. P (“Practice”) indicates themes that refer to how knowledge is shared/institutionalized within the team: for example, communally developed resources in support of the domain, such as lesson plans for LLCs or video/worksheet content for TYRIT, and how this content is delivered. C (“Community”) indicates themes that refer to affective/relational work that takes place between team members to maintain the social group: for example, feeling a sense of belonging to the team and how professional relationships develop between team members.

How do members experience the community aspect of our CoP? Community was experienced to an extent in effective/productive interactions between facilitators, but practice-related benefits of the CoP are those primarily experienced in effective/productive interactions between facilitators (Table 1). However, community was experienced to a much greater extent as a source of satisfaction/personal fulfillment. The senses of community experienced by facilitators as a source of satisfaction/personal fulfillment are deeper than those experienced in effective/productive interactions between facilitators (Tables 2 and 3).

Themed Experiences and Representative Quotations Sourced in Effective/Productive Interactions

Theme |

Community perspective |

|

|---|---|---|

Within institution |

Across institution |

|

Sharing ideas (D and P) |

“Usually each of us only had maybe one idea for something to do. When we combined our ideas, not only did they grow in number, they grew in sophistication. We combined approaches to develop activities that each would have been better (more interactive … richer in content) than they were originally conceived.” (Q10, #3) |

“I loved getting to see and hear from a group of people who are all passionate about teaching, especially when they had so many different ways to approach the same weekly content. Seeing that variety inspired me to be creative in how I approached planning the weekly local community meetings and I think I developed several things that I would not have if I was not able to see what the facilitators at other institutions were doing.” (Q15, #7) |

Efficiency (P) |

“Our brain-storming sessions each week were highly productive. It was pretty crazy how we could all come in with our own ideas about activities and within 20 min already have a working model for the session (usually incorporating everyone’s ideas in one way or another).” (Q10, #12) |

|

Meaningful contributions to the team (C and P) |

“We had several meetings to talk about planning and then met to check in during the course so people felt like they knew what was going on and that their input was valued.” (Q15, #8) |

|

|

Supportive leadership (C and P) |

“I felt supported by their intelligence and dedication because my own time was so very short. I could not have done this without them.” (Q15, #5) |

|

Note. Each theme is tagged with its associated domain(s) of a CoP: D = Domain, P = Practice, C = Community.

Themed Experiences and Representative Quotations Sourced in Satisfying/Personally Fulfilling Interactions

Theme |

Community perspective |

|

|---|---|---|

Within institution |

Across institution |

|

Belonging: mentor/mentee relationships (C) |

“I enjoyed working with a person who was brand new to grad student development and watching her find her voice.” (Q11, #3) |

|

|

Belonging: personal and professional friendships (C) |

“I am so grateful for the deep friendships I have from this inter-institutional collaboration and that applies to both professional and personal relationships.” (Q16, #2) |

|

Validation through contributions (C) |

“The interaction made me feel that both my ideas and work were valid and important.” (Q11, #12) |

“I was so quickly welcomed into the group and made to feel that I belonged and my contributions were valued. This makes a big difference to me as a graduate student that has had struggles with my adviser and members of my department looking down on the career path that I am pursuing.” (Q16, #7) |

Mutual sense of care (C) |

“Working with the across-network team helped me feel supported and motivated” (Q16, #8) |

|

Stress relief/fun (C) |

“It … made all of the other things I have in my life easier too.” (Q11, #9) |

“I like the laid back and fun tone of this group.” (Q16, #10) |

Relief during COVID-19 pandemic (C) |

“It was nice to be doing some work that was enjoyable during a time when not many things are.” (Q16, #11) |

|

Learning with and from one another (D and P) |

“I really enjoy working with my co-facilitator, we … can pull from a lot of valuable … past experiences which I think the participants benefited from.” (Q11, #11) |

“I enjoyed getting to know new people and hearing different perspectives about the course material. I enjoyed the emails from leaders about how different activities went for their groups or how their students were engaging with the material.” (Q16, #8) |

Note. Each theme is tagged with its associated domain(s) of a CoP: D = Domain, P = Practice, C = Community.

Experiences From Within-Institution Groups

Experiences in Effective/Productive Interactions

Facilitators experienced primarily practice-related benefits, along with some domain-related benefits, in effective/productive interactions within the same institution (Table 2). Some facilitators identified sharing ideas as a practice- and domain-related benefit. Other facilitators referred to sharing ideas as something that benefited the quality of the TYRIT material itself. Facilitators who identified efficiency as a benefit referred in particular to the planning of the weekly, synchronous meetings for program participants and the navigation of new technology.

Experiences in Satisfying/Personally Fulfilling Interactions

When asked what facilitators found most satisfying or personally fulfilling about collaborating with other facilitators within the same institution, responses identified primarily community-related benefits, along with some practice- and domain-related benefits (Table 3).

Community-related benefits included a sense of belonging and professional support in facilitator subgroups from individual institutions. This was experienced consistently among graduate student, faculty, and staff respondents. Responses in this category often described relationships within their institution’s professional framing (e.g., colleague, mentor/mentee). Where mentor-mentee relationships were present in teams at individual institutions, mentors enjoyed seeing new facilitators develop. Contributing to the collaboration was described as validating for members of the team. There was an overall sense that collaborations among facilitators within individual institutions were stress relieving/fun.

Domain- and practice-related benefits were found in responses that described benefits of learning with and from one another. We note that the focus here is on the personal enjoyment of working with colleagues with diverse perspectives rather than on productive work in and of itself.

Experiences From Across-Institution Groups

Experiences in Effective/Productive Interactions

As when asked about within-institution experiences, when asked what facilitators found most effective or productive about collaborating with other facilitators across different institutions, facilitators primarily identified practice-related elements of the CoP, while some identified domain-related elements of the CoP (Table 2). Again, the benefits of sharing ideas was a common theme that emerged, described in both a practical context and as something that benefited the quality of the TYRIT material itself.

However, facilitators also experienced community in across-institutional collaborations that derived from effective/productive interactions. Facilitators connected the organization of the program to the sense of community it fosters via meaningful contributions. Other facilitators described an appreciation for the central organization and supportive leadership of the TYRIT program, eliciting a general feeling that the functioning of the whole facilitator team served as a role model for individual institutions to emulate.

Experiences in Satisfying/Personally Fulfilling Interactions

Facilitators experienced a sense of belonging as a contributor to community satisfaction, enacted by developing/reestablishing existing relationships. As in the within-institution category, this was consistently experienced by many respondents. However, across institutions, these experiences were often described using personal language (e.g., connection, friendship), suggesting that the satisfaction underlain by this sense of belonging stemmed from blending of professional and personal relationships.

Relatedly, facilitators felt validated by the community for ideas and contributions that were encouraged through the collaborative structure. A mutual sense of care was experienced by facilitators who described the collaborative work as satisfying/personally fulfilling. The sense of support and motivation from the community supported their individual work. There were also comments that indicated these feelings derived from exemplary across-institutional leadership in the TYRIT community.

A unique feature of the satisfaction-related across-institution responses was mention of the COVID-19 pandemic. As with experiences from the perspective of a single institution, community members found TYRIT to be stress relieving and fun. But unlike for experiences from the perspective of a single institution, facilitator responses across institutions experienced this relief specifically in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar to within-institution groups, facilitators experienced domain and practice-related benefits of learning with and from colleagues across institutions. These benefits described enjoyment of hearing about different experiences happening in parallel at other institutions.

Themed Experiences Unique to Each Community Perspective

Recall Table 1, in which we summarized themes from facilitators’ experiences in within- and across-institution communities. Compare Table 1 to Table 4, in which we remove themes that are found both across institutions and within individual institutions.

Themed Experiences Unique to Within-Institution/Across-Institution Communities

Source of experience |

Community perspective |

|

|---|---|---|

Within institution |

Across institution |

|

|

Effective/ productive interactions |

|

|

|

Satisfying/ personally fulfilling interactions |

|

|

Note. All themes that were present in both within- and across-institution responses were removed to highlight these key unique themes. Each theme is tagged with its associated domain of a CoP: D = Domain, P = Practice, C = Community.

What is the value of the across-institutional aspect of our CoP in sustaining our CoP? Key sustaining factors of a multi-institution, cross-network CoP are all community related (Table 4). Specifically, these benefits are representative of several themes that emerged in members’ experiences of community in our CoP: an increased sense of belonging (through positive social interactions, being connected and working against isolation) and a heightened sense of mutual care between colleagues.

Other Experiences of Community From an Across-Institutional Perspective

What is the value of the across-institutional aspect of our CoP in sustaining our CoP? We also analyzed survey responses to a further set of questions. In this set of questions, facilitators were asked: (Q20) what, if anything, they learned from any of the other facilitators; (Q21) how the collaboration contributed to their professional development; and (Q22) whether there were any unexpected outcomes/experiences that came from their collaborations.

For several facilitators, professional development meant being part of an across-institution network, and responses to Q21 elicited a rich variety of community-related experiences. These experiences included a sense of meaning and purpose, mutual care among facilitators, and a sense of enjoyment derived from being part of a larger team. For instance, one facilitator wrote, “I’m really proud to be part of the research projects from this course. The whole experience has given me a lot of personal and professional meaning and purpose” (Q21, #2). Another facilitator wrote, “This collaboration helps me by continuing to have connection outside of my institution. I do not have a large community here that cares as much about teaching and learning, so I need this” (Q21, #9). Yet another facilitator wrote, “I really enjoyed getting to know the other facilitators from all the institutions and learning from them. I think this network and these partnerships will continue beyond this project and we will hopefully continue to work together” (Q22, #8).

A striking feature of the responses to Q20–Q22 was the relationship between responses that (a) referenced some across-institutional aspect of the overall collaboration and (b) included affective/emotive/feeling words associated with the above community-related experiences. By across-institutional aspect we mean a reference to a variety of members, or to all members, of the facilitator network, including references to research projects (21 responses out of 41 total). Affective/emotive/feeling words include the following, along with any associated derivatives: “excited,” “connection,” “enjoy,” “care,” “happy,” “fun,” “proud,” “brilliant,” “kind,” “looking forward,” “rewarding,” “relaxing,” “amazing,” “meaning,” “reminds me to breathe,” “inspired,” and “hopeful.” These occurrences appeared in 25 total responses to Q20–Q22. Of the 25 responses to Q20–Q22 that included affective/emotive/feeling words, 21 referenced some across-institutional aspect of the overall collaboration (84%). Of the 21 responses that referenced some across-institutional aspect of the overall collaboration, all of them contained at least one occurrence of an affective/emotive/feeling word.

Discussion

We comment briefly on the finding that efficiency was experienced uniquely from the perspective of facilitators at single institutions, and that supportive leadership was experienced uniquely from the perspective of facilitators across institutions, before discussing the remaining community-related benefits of Table 4.

Efficiency of preparing content for weekly delivery at their home institutions in LLCs was the only experience unique to within-institution sub-communities and was the only practice-related experience identified from either community perspective. An explanation for this observation is that the practicalities of planning and delivering weekly LLCs were carried out at the within-institution level, as a responsibility of subgroups of one to three facilitators at their respective home institutions. While the whole facilitator team met synchronously online occasionally to share ideas about course material, ideas that formed some basis of LLC preparation at home institutions, the preparation of LLCs largely took place at the within-institution level.

However, facilitators experienced supportive leadership across institutions, likely because interactions between facilitators and the CoP leadership team mostly occurred during the synchronous online meetings that involved the whole facilitator network. The support of the leadership team was most tangible in the across-institutional setting where scheduling, organization, agendas, and facilitation of those meetings were carried out by the leadership team before and during these meetings. We suggest that the remaining community-related experiences unique to an across-institution perspective are related to mutual care and a sense of belonging among facilitators.

Mutual care between members of a CoP is a robust phenomenon that offers educational developers insights into how members of our CoP support one another in community in order to engage in practice. A CoP is more than the accounting of the members, their shared interest, and the intellectual products they produce. Different from networked improvement communities, which focus on applying improvement science approaches to study a problem and on the adaptability and reliability of solutions to multiple contexts, CoPs focus more on how the community can support members’ practice as they learn from and with one another (LeMahieu, 2015). CoPs nurture ways of working together to sustain the community and further members’ sense of purpose and belonging (Chen et al., 2022; Drane et al., 2019; Hoffmann et al., 2021; Korsnack & Ortquist-Ahrens, 2021). It involves a dynamic relationship of both protective and nurturing caregiving, “a mutual practice of giving and receiving” (hooks, 2000; Jordan, 2008). CoPs operate as psycho-social holding environments that promote members’ simultaneous differentiation and integration of their professional, social, and personal selves (Kegan, 1982). Thus, the CoP can also be understood as a social, emotional, and cognitive learning organization for the members themselves, not just for the primary beneficiaries of the community’s products and services.

Members support one another’s growth and individuality with affective/emotional labor as they contribute to the group’s collective practice, similar to the work in ED/client relationships (Bessette & McGowan, 2020; Chen et al., 2022; Imad, 2021). We noticed this interaction and benefit in our community-through-teamwork theme, which was uniquely associated with across-institutional responses. CoPs are also important places of rest, recuperation, and reset for educational developers when they experience secondary and vicarious distress as a result of emotional dysregulation in an instructor (van Dernoot Lipsky & Burk, 2009). We notice this community-mutual care experience in this study when our respondents identified relief from the distress of the COVID-19 pandemic as an important across-institutional benefit.

In addition to offering a means for analyzing knowledge creation and the social process of learning, CoPs also offer a way to analyze belonging mechanisms (Anthony et al., 2020). Belonging is enacted through mutual engagement, whereby community members interact at different levels and in various ways; shared repertoire, whereby members of a CoP learn from one another through practices; and negotiation of a joint enterprise, whereby members collaborate to make decisions about how the CoP will function, including decisions about the nature and significance of the group itself (Anthony et al., 2020, pp. 768–769; Iverson & McPhee, 2002, p. 261). Thus, belonging exists at two levels. First, CoPs are interrelated, possibly hierarchical, sub-communities that function together as a meaningful whole (Scott et al., 1998). Second, a CoP transcends hierarchies and the individualistic focus of identification within those sub-communities (Iverson, 2011, p. 48). We suggest that this dual-level enactment of belonging is reflected in facilitators’ experiences in our CoP. Within institutions, we find belonging enacted in mentor-mentee relationships, in which mentors enjoy seeing their mentees develop. Across institutions, we find a sense of belonging that transcends hierarchical relationships, experienced as the blending of personal and professional relationships.

For educational developers, CoPs resolve role isolation. Whereas we might be the one person performing a function at our institution, an inter-organizational CoP brings together people who want to collaboratively solve a problem but who are physically, geographically, or organizationally separated (Chen et al., 2022; Korsnack & Ortquist-Ahrens, 2021). CoPs also might be sites of important mentorship and networking experiences that support professional development while members co-learn from others sharing their roles in other organizations (Donnell et al., 2018; Drane et al., 2019; Lave & Wenger, 1991). These mentorship experiences are particularly important considering that the majority of practitioners in ED have advanced training in an academic discipline, not in education (Kearns et al., 2018; POD Network, 2016). Thus, CoPs form an organizational, professional, and social bridge between day-to-day operations at their home institutions and annual professional meetings among participants from many institutions.

Implications for the Field of Educational Development

Facilitators who responded to the survey had a few suggestions for improving the functioning and value of the TYRIT 2020 CoP. Their recommendations are influenced by specificities of our TYRIT workshop series and the COVID-19 global pandemic (this study was conducted in June and July 2020 shortly after most in-person activities in the United States went virtual until August). Here we share some generalizable considerations for planning the day-to-day and week-to-week of a CoP, based on our participants’ reflections. We also offer readers, as fellow practitioners in ED, broader recommendations about leading and participating in CoPs.

Specific Considerations for Community of Practice Design

Frequency of Meetings

In 2020, we held one meeting before the workshop series began, one meeting just before the mid-point as a check-in, and one meeting near the end to address details for the last week of the series. Even though multiple respondents mentioned that they were just keeping up, we also heard from facilitators who wanted optional weekly meetings. One facilitator also requested a meeting after the workshop series to reflect and debrief.

Size of Community

With almost 20 facilitators in our whole-group meetings, multiple respondents felt that the group was too large for some conversations. These same respondents encouraged the use of breakout rooms for a portion of our meeting time so that they could engage in deeper conversations with a smaller group of people and get to know people beyond their home institution better. One respondent suggested pairing up facilitator teams to share insights regularly and form stronger across-institutional networks.

Sharing Practices

While our shared online repository of weekly LLC activities was mentioned repeatedly as a valuable asset of the TYRIT CoP, a couple of respondents were frustrated with the lack of standardization of what practices were shared and how we shared those practices. They noted that not all participating institutions were posting their weekly plans to the repository, reducing the effectiveness of the across-institutional component of our CoP. Another respondent suggested that the leaders link to that week’s repository as part of their weekly announcement emails as a regular reminder of that resource.

Shared, Distributed Leadership

Several respondents appreciated the variety of opportunities for division of labor within the TYRIT CoP, based on their time availability, energy, and interest. At the same time, a couple of respondents offered suggestions for how to continue moving toward a more distributed effort model. In large part, this request overlapped with recommendations for smaller breakout discussions, demonstrating the value members placed on the experiences of their colleagues. Another respondent suggested having a CoP meeting before the workshop series starts when experienced TYRIT facilitators can describe their approach to designing and leading their weekly LLCs.

Broader Considerations for Community of Practice Organization and Participation

Listen for Participants’ Meaning-Making About Community

In a dominant culture of efficiency and productivity, our work—and perhaps even our sense of self-worth—prioritizes and gives value to products and their impacts. However, this study elucidates the value of community to CoP participants, aside from the products. Our participants shared the meanings they made of the community and how their experience fit into their personal and professional story. We encourage reader-practitioners of ED to give space to listen deliberately for their participants’ narratives of belonging and growth in their CoPs.

Design for Community

Because our field of ED emphasizes a backward design approach (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005), we suspect that a typical CoP is designed with the outcome first, usually reflected as practice. In comparison, the leaders of TYRIT prioritized facilitator interactions that had low hierarchy, high interdependence and reciprocity, and high validation of agency and authority. Our respondents noted that the across-institutional leadership experiences supported both their practice and well-being. We recommend that leaders and facilitators of CoPs intentionally plan for relational and human growth potential in the interaction space of their communities.

Support the Formation of Inter-Institutional Communities for Educational Developers

Educational developers are likely familiar with facilitating faculty learning communities, a form of CoP in which faculty members from different disciplines support developing pedagogical practice (Cox, 2004). Similarly, learning communities for educational developers are spaces to share expertise and engage in professional learning (Donnell et al., 2018; Lave & Wenger, 1991). Our study extends the suggestion of Donnell et al. (2018) in two dimensions by identifying the across-institutional composition as a notable factor in the experience of CoPs that has a beneficial impact on educational developers’ well-being. While organizing a learning community among professionals within the same office is likely simpler, we emphasize the importance of across-institutional membership in CoPs. These CoPs are composed of educational developers from different institutional communities who share interests and experiences in domains and practices. Recalling Kegan’s (1982) psycho-social holding environment concept (p. 115), members of across-institutional CoPs can readily understand and empathize with a domain- or practice-specific problem; can offer new suggestions and broader perspectives; are detached from specific emotional contexts of other members’ office- or campus-specific issues; and can engage in reciprocal, dynamic, balanced, and compassionate support about concerns.

Limitations

Several important limitations should be considered in the interpretation of this study. First, the case study design makes it impossible to establish cause and effect between the processes that took place and the outcomes that were observed. What we show here is an example of what is possible in a well-built CoP. The naturalistic setting for the research also carries some fundamental limitations such as a limited sample size and variation in the size of the various teams, both at each institution and in the across-institutional teams. The nature of the research as a self-study is both an advantage and a disadvantage. On one hand, a self-study allows for deep knowledge of internal processes that define this particular CoP and a level of reflection that would be challenging for a neutral observer to integrate. On the other hand, this level of internal awareness leads to natural bias in the interpretation of results. The research approach emphasized multiple layers of analysis to reduce individual bias, but it is possible that the ethic of the CoP itself influenced the reading of the results by all of the research team members. Finally, because the CoP was derived from members of a preexisting professional society (CIRTL Network), it’s possible that preexisting relationships between the community members led to higher-than-average involvement and a skew in the data toward themes of friendship and belonging. We don’t see this as a limitation but more as an insight that CoPs may benefit by growing out of existing communities or professional organizations to maximize their potential for interpersonal connection and growth.

Conclusion

This study, in joining other examples of CoPs in ED, contributes to understanding how CoP members experience community and the value of across-institutional structural elements of CoPs. In delivering a hybrid course design institute for graduate students and postdoctoral scholars across institutions, facilitators in the community reap specific gains: (1) an increased sense of belonging (through positive social interactions; increased possibilities for mentoring, networking, and collaboration; being connected; and working against isolation); (2) personal and professional validation within the field of ED (with enhanced feelings of meaning, purpose, fulfillment, affirmation, and hopefulness and alignment with the values of our field in collaboration and intellectual generosity); and (3) giving care and accepting care from colleagues.

Our CoP resulted in benefits for participants that coincide with studies of collaborative research more generally: resource sharing, time-saving/efficiency, learning opportunities, innovation, and mutual trust (Bozeman & Boardman, 2014; San Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2005; Turrini et al., 2010). In the context of CoPs, participants reported benefits such as belonging, knowing-in-practice, knowledge sharing, and thinking together (Iverson, 2011; Kuhn & Jackson, 2008; McDermott, 2000; Nicolini, 2011; Orlikowski, 2002; Pyrko et al., 2017; Rennstam & Ashcraft, 2014). At the root, these benefits point to the purpose of producing something in an economically and intellectually competitive environment. Our case study of participants’ experiences in a CoP—in which resources of time, ideas, and mentoring are abundant and generously shared—confirms that this collaborative social system additionally supports members’ well-being and growing sense of self.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the “CIRTL Central” team, especially Kate Diamond and Kitch Barnicle, who provided the logistical, technical, and relational support that has enabled us to facilitate the TYRIT workshop series for members of the international CIRTL Network for multiple years. We are especially grateful for the friendship, wisdom, compassion, patience, and expertise of our TYRIT co-facilitators for being on this collaboration journey with us and for continually reflecting back to us what has mattered most to them. Thank you to the graduate students and postdocs of TYRIT for sharing their passion for their research and their commitment to being effective teachers; you and your projects inspire us to keep providing this space for learning and growing. Speaking on behalf of all TYRIT facilitators, we are grateful to our academic employers for supporting our time and effort as we lead TYRIT, coach future faculty, mentor developing professionals, and contribute to meaningful practice in the field of educational development. Finally, thank you to Dr. Chris Chen for his insightful feedback on an earlier draft of this article.

Biographies

Thomas M. Colclough holds a PhD from the Department of Logic and Philosophy of Science at the University of California, Irvine. His educational research interests focus on trauma-informed pedagogical approaches. He also teaches about teaching and is interested in graduate student development and in strategies for reducing achievement gaps in STEM-based courses delivered outside of STEM fields.

William J. Howitz is an Assistant Professor and the Organic Laboratory Director in the Department of Chemistry at the University of Minnesota. In addition to teaching undergraduate organic chemistry lecture and laboratory courses, he is responsible for the training and mentorship of graduate teaching assistants. His scholarly interests include the evaluation of alternative grading systems, such as specifications grading, and the development of argument-driven inquiry experiments for undergraduate chemistry laboratory courses.

Danny Mann is the Executive Director for the Division of Teaching Excellence and Innovation at the University of California, Irvine. His research, teaching, and service focus on equitable pedagogy, professional development, and supportive interdisciplinary communities. Dr. Mann serves as a leader in multiple cross-institutional educational development networks, including POD Network’s Core Committee; the Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching, and Learning (CIRTL); and the University of California Centers for Teaching and Learning Consortium.

Katherine Kearns, PhD, collaborates with colleagues in higher education to support the persistence, professional skill development, and career preparation of graduate students and postdoctoral scholars. Her scholarly interests include identity development, well-being, and belonging of marginalized graduate students. She was most recently the Assistant Vice Provost for Student Development and Director of the Office of Postdoctoral Affairs in the University Graduate School at Indiana University Bloomington.

Darren S. Hoffmann is an Associate Professor of Anatomy and Cell Biology at the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine. He teaches medical students, dental students, and graduate students. He conducts research on anatomy education and graduate student development.

References

Abeysekera, L., & Dawson, P. (2015). Motivation and cognitive load in the flipped classroom: Definition, rationale and a call for research. Higher Education Research & Development, 34(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.934336https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2014.934336

Anthony, K. E., Reif-Stice, C. E., Iverson, J. O., & Venette, S. J. (2020). Belonging in practice: Using communities of practice theory to understand support groups. In H. D. O’Hair & M. J. O’Hair (Eds.), The handbook of applied communication research (pp. 765–779). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119399926.ch42https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119399926.ch42

Argote, L., & Ingram, P. (2000). Knowledge transfer: A basis for competitive advantage in firms. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 82(1), 150–169. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2893https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.2000.2893

Austin, A. E., & McDaniels, M. (2006). Preparing the professoriate of the future: Graduate student socialization for faculty roles. In J. C. Smart (Ed.), Higher education: Handbook of theory and research (Vol. 21, pp. 397–456). Springer.

Bang, H., & Midelfart, T. N. (2017). What characterizes effective management teams? A research-based approach. Consulting Psychology Journal: Practice and Research, 69(4), 334–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000098https://doi.org/10.1037/cpb0000098

Bessette, L. S., & McGowan, S. (2020). Affective labor and faculty development: COVID-19 and dealing with the emotional fallout. Journal on Centers for Teaching and Learning, 12, 136–148. https://openjournal.lib.miamioh.edu/index.php/jctl/article/view/212/116https://openjournal.lib.miamioh.edu/index.php/jctl/article/view/212/116

Border, L. L. B., & von Hoene, L. M. (2010). Graduate and professional student development programs. In K. J. Gillespie & D. L. Robertson (Eds.), A guide to faculty development (2nd ed., pp. 327–346). Jossey-Bass.

Bouchamma, Y., April, D., & Basque, M. (2018). How to establish and develop communities of practice to better collaborate. Canadian Journal of Educational Administration and Policy, 187, 91–105. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1197558.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1197558.pdf

Bozeman, B., & Boardman, C. (2014). Assessing research collaboration studies: A framework for analysis. In Research collaboration and team science (pp. 1–11). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06468-0_1https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-06468-0_1

Chen, C. V. H.-H., Kearns, K., Eaton, L., Hoffmann, D. S., Leonard, D., & Samuels, M. (2022). Caring for our communities of practice in educational development. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 41(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.460https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.460

Cox, M. D. (2004). Introduction to faculty learning communities. New Directions for Teaching & Learning, 2004(97), 5–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.129https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.129

Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications.

Donnell, A. M., Fulmer, S. M., Smith, T. W., Bostwick Flaming, A. L., & Kowalik, A. (2018). Educational developer professional development map (EDPDM): A tool for educational developers to articulate their mentoring network. Journal on Centers for Teaching and Learning, 10, 3–23. https://openjournal.lib.miamioh.edu/index.php/jctl/article/view/195/100https://openjournal.lib.miamioh.edu/index.php/jctl/article/view/195/100

Drane, L. E., Lynton, J. Y., Cruz-Rios, Y. E., Malouchos, E. W., & Kearns, K. D. (2019). Transgressive learning communities: Transformative spaces for underprivileged, underserved, and historically underrepresented graduate students at their institutions. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 7(2), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.7.2.7https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.7.2.7

Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th anniversary ed.). Continuum. (Original work published 1968)

Gehrke, S., & Kezar, A. (2017). The roles of STEM faculty communities of practice in institutional and departmental reform in higher education. American Educational Research Journal, 54(5), 803–833. https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217706736https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831217706736

Grossoehme, D. H. (2014). Overview of qualitative research. Journal of Health Care Chaplaincy, 20(3), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2014.925660https://doi.org/10.1080/08854726.2014.925660

Guberman, A., Avidov-Ungar, O., Dahan, O., & Serlin, R. (2021). Expansive learning in inter-institutional communities of practice for teacher educators and policymakers. Frontiers in Education, 6, Article 533941. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.533941https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.533941

Hadar, L. L., & Brody, D. L. (2018). Individual growth and institutional advancement: The in-house model for teacher educators’ professional learning. Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.007https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.007

Hoffmann, D. S., Kearns, K. D., Bovenmyer, K. M., Cumming, W. F. P., Drane, L. E., Gonin, M., Kelly, L., Rohde, L., Tabassum, S., & Blay, R. (2021). Benefits of a multi-institutional, hybrid approach to teaching course design for graduate students, postdoctoral scholars, and leaders. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 9(1), 218–240. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.9.1.15https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.9.1.15

Hoffmann, D. S., & Lenoch, S. (2013). Teaching your research: A workshop to teach curriculum design to graduate students and post-doctoral fellows. Medical Science Educator, 23(3), 336–345. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03341645https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03341645

hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

hooks, b. (2000). All about love: New visions. William Morrow.

Hoyert, M., & O’Dell, C. (2019). Developing faculty communities of practice to expand the use of effective pedagogical techniques. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 19(1), 80–85. https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v19i1.26775https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v19i1.26775

Imad, M. (2021). Transcending adversity: Trauma-informed educational development. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 39(3), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.301https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.301

Iverson, J. O. (2011). Knowledge, belonging, and communities of practice. In H. E. Canary & R. D. McPhee (Eds.), Communication and organizational knowledge: Contemporary issues for theory and practice (pp. 35–52). Routledge.

Iverson, J. O., & McPhee, R. D. (2002). Knowledge management in communities of practice: Being true to the communicative character of knowledge. Management Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1177/089331802237239https://doi.org/10.1177/089331802237239

Jimenez-Silva, M., & Olson, K. (2012). A community of practice in teacher education: Insights and perceptions. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 24(3), 335–348.

Jordan, J. V. (2008). Valuing vulnerability: New definitions of courage. Women & Therapy, 31(2–4), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140802146399https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140802146399

Kapucu, N. (2012). Classrooms as communities of practice: Designing and facilitating learning in a networked environment. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 18(3), 585–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2012.12001701https://doi.org/10.1080/15236803.2012.12001701

Kearns, K., Hatcher, M., Bollard, M., DiPietro, M., Donohue-Bergeler, D., Drane, L. E., Luoma, E., Phuong, A. E., Thain, L., & Wright, M. (2018). “Once a scientist … ”: Disciplinary approaches and intellectual dexterity in educational development. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 37(1), 128–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20072https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20072

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Harvard University Press.

Kirkman, B. L., Mathieu, J. E., Cordery, J. L., Rosen, B., & Kukenberger, M. (2011). Managing a new collaborative entity in business organizations: Understanding organizational communities of practice effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 96(6), 1234–1245. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024198https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024198

Korsnack, K., & Ortquist-Ahrens, L. (2021). Holding tight to our convictions and lightly to our ways: Inviting shared expertise as a strategy for expanding inclusion, reach, and impact. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 39(3), 133–150. https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.309https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0039.309

Kozlowski, S. W. J., & Ilgen, D. R. (2006). Enhancing the effectiveness of work groups and teams. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 7(3), 77–124. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00030.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1529-1006.2006.00030.x

Kuhn, T., & Jackson, M. H. (2008). Accomplishing knowledge: A framework for investigating knowing in organizations. Management Communication Quarterly, 21(4), 454–485. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318907313710https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318907313710

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

LeMahieu, P. (2015, August 18). Why a NIC? Carnegie Commons Blog. https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/blog/why-a-nic/https://www.carnegiefoundation.org/blog/why-a-nic/

Lovitts, B. E. (2001). Leaving the ivory tower: The causes and consequences of departure from doctoral study. Rowman & Littlefield.

Lovitts, B. E. (2004). Research on the structure and process of graduate education: Retaining students. In D. H. Wulff & A. E. Austin (Eds.), Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty (pp. 115–136). Jossey-Bass.

Margolin, I. (2011). Professional development of teacher educators through a “transitional space”: A surprising outcome of a teacher education program. Teacher Education Quarterly, 38(3), 7–25.

McDermott, R. (2000). Knowing in community: 10 critical success factors in building communities of practice. International Association for Human Resource Management, 4(1), 19–26.

Nerad, M., Aanerud, R., & Cerny, J. (2004). “So you want to become a professor!”: Lessons from the PhDs—Ten years later study. In D. H. Wulff & A. E. Austin (Eds.), Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty (pp. 137–158). Jossey-Bass.

Nicolini, D. (2011). Practice as the site of knowing: Insights from the field of telemedicine. Organization Science, 22(3), 602–620. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0556https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0556

Nyquist, J. D., Woodford, B. J., & Rogers, D. L. (2004). Re-envisioning the Ph.D.: A challenge for the twenty-first century. In D. H. Wulff & A. E. Austin (Eds.), Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty (pp. 194–216). Jossey-Bass.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2002). Knowing in practice: Enacting a collective capability in distributed organizing. Organization Science, 13(3), 249–273. https://doi.org/10.3280/so2008-002007https://doi.org/10.3280/so2008-002007

Palmer, M. S. (2011). Graduate student professional development: A decade after calls for national reform. In L. B. B. Border (Ed.), Mapping the range of graduate student professional development: Studies in graduate and professional student development (pp. 1–18). New Forums Press.

Palmer, M. S., Streifer, A. C., & Williams-Duncan, S. (2016). Systematic assessment of a high-impact course design institute. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 35(2), 339–361. https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0035.203https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0035.203

POD Network. (2016). The 2016 POD network membership survey: Past, present, and future. https://podnetwork.org/content/uploads/2016podmembershipreportprintnomarks.pdfhttps://podnetwork.org/content/uploads/2016podmembershipreportprintnomarks.pdf

Pyrko, I., Dörfler, V., & Eden, C. (2017). Thinking together: What makes communities of practice work? Human Relations, 70(4), 389–409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716661040https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726716661040

Rennstam, J., & Ashcraft, K. L. (2014). Knowing work: Cultivating a practice-based epistemology of knowledge in organization studies. Human Relations, 67(1), 3–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713484182https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713484182

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

San Martín-Rodríguez, L., Beaulieu, M.-D., D’Amour, D., & Ferrada-Videla, M. (2005). The determinants of successful collaboration: A review of theoretical and empirical studies. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(Suppl. 1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082677https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082677

Scott, C. R., Corman, S. R., & Cheney, G. (1998). Development of a structurational model of identification in the organization. Communication Theory, 8(3), 298–336. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.1998.tb00223.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.1998.tb00223.x

Soekijad, M., Huis in ’t Veld, M. A. A., & Enserink, B. (2004). Learning and knowledge processes in inter-organizational communities of practice. Knowledge and Process Management, 11(1), 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.191https://doi.org/10.1002/kpm.191

Teeter, C., Fenton, N., Nicholson, K., Flynn, T., Kim, J., McKay, M., O’Shaughnessy, B., & Vajoczki, S. (2011). Using communities of practice to foster faculty development in higher education. Collected Essays on Learning and Teaching, 4, 52–57. https://doi.org/10.22329/celt.v4i0.3273https://doi.org/10.22329/celt.v4i0.3273

Turrini, A., Cristofoli, D., Frosini, F., & Nasi, G. (2010). Networking literature about determinants of network effectiveness. Public Administration, 88(2), 528–550. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01791.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01791.x

van Dernoot Lipsky, L., & Burk, C. (2009). Trauma stewardship: An everyday guide to caring for self while caring for others. Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Vincent, K., Steynor, A., Waagsaether, K., & Cull, T. (2018). Communities of practice: One size does not fit all. Climate Services, 11, 72–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2018.05.004https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2018.05.004

Webb, A. S., & Welsh, A. J. (2019). Phenomenology as a methodology for scholarship of teaching and learning research. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 7(1), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.7.1.11https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.7.1.11

Webber, E., & Dunbar, R. (2020). The fractal structure of communities of practice: Implications for business organization. PLoS ONE, 15(4), Article e0232204. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232204https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232204

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511803932

Wenger, E. (2001). Communities of practice and social learning systems. In F. Reeve, M. Cartwright, & R. Edwards (Eds.), Supporting lifelong learning: Vol. 2. Organising Learning (pp. 160–179). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203996720https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203996720

Wenger, E., McDermott, R. A., & Snyder, W. (2002). Cultivating communities of practice: A guide to managing knowledge. Harvard Business Review Press.

Wenger, E. C., & Snyder, W. M. (2000). Communities of practice: The organizational frontier. Harvard Business Review, 78(1), 139–145.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by design (2nd ed.). Pearson.

Wulff, D. H., Austin, A. E., Nyquist, J. D., & Sprague, J. (2004). The development of graduate students as teaching scholars: A four-year longitudinal study. In D. H. Wulff & A. E. Austin (Eds.), Paths to the professoriate: Strategies for enriching the preparation of future faculty (pp. 46–73). Jossey-Bass.

Appendix TYRIT 2020: Instructor Survey Multi-Institutional Collaboration

Part A

-

Q6a.

What is your primary role on campus?

□ Graduate student

□ Postdoctoral scholar

□ Staff

□ Faculty

-

Q6b.

Did you work with the TYRIT team in 2019?

□ Yes

□ No

-

Q7.

Approximately how much time did you invest each week preparing and leading the local community meetings?

□ < 1 hour per week

□ 1–2 hours per week

□ 2–3 hours per week

□ 3–4 hours per week

□ 4–5 hours per week

□ > 5 hours per week

-

Q8.

Were you the sole facilitator at your institution, or did you work as part of a team of facilitators at your institution?

□ Sole facilitator

□ Worked as a team within my institution

Part B

-

Q9.

Approximately how often did you check in/meet with your institutional team separately from the whole team?

□ More than once a week

□ Weekly

□ Every two weeks

□ Monthly

□ Never

-

Q10.

What did you find MOST effective or productive about collaborating with facilitators within your institution?

-

Q11.

What did you find MOST satisfying or personally fulfilling about collaborating with facilitators within your institution?

-

Q12.

What recommendations would you have for improving the effectiveness of and your satisfaction with these within-institution collaborations?

-

Q13.

Indicate the extent to which your contributions to the following aspects of the within-institution collaborations make you feel a part of a community.

Not at all |

Hardly |

Neutral |

A little |

Quite a bit |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Facilitator meetings |

|||||

Emails among facilitators (sharing ideas, asking questions) |

|||||

Opportunities to learn with and from other workshop leaders |

|||||

Contributing to workshop/lesson plans |

|||||

Contributing to managing the learning community |

Other:

Part C

-

Q14.

Approximately how often did you check in or meet with people outside your institution?

□ More than once a week

□ Weekly

□ Every two weeks

□ Monthly

□ Never

-

Q15.

What did you find MOST effective or productive about collaborating with facilitators across different institutions?

-

Q16.

What did you find MOST satisfying or personally fulfilling about collaborating with facilitators across different institutions?

-

Q17.

What recommendations would you have for improving the effectiveness of and your satisfaction with these cross-institution collaborations?

-

Q18.

In what ways (if any) did the cross-network collaborations influence your time investment needed to develop and run your weekly workshops?

-

Q19.

Indicate the extent to which your contributions to the following aspects of the cross-network collaborations make you feel a part of a community.

Not at all |

Hardly |

Neutral |

A little |

Quite a bit |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Facilitator meetings |

|||||

Emails among facilitators (sharing ideas, asking questions) |

|||||

Opportunities to learn with and from other workshop leaders |

|||||

Contributing to content development |

|||||

Contributing to managing the course |

|||||

Contributing to the program evaluation of the course |

-

Other:

-

Q20.

What, if anything, did you learn from ANY of the facilitators of TYRIT? Please provide specific examples (e.g., workshop activities, organization and management approaches).

-

Q21.

How, if at all, do you think participating in this collaboration contributed to your professional development?

-

Q22.

Overall, what was an unexpected outcome/experience that came from your collaborations in TYRIT?