As the scholarly literature suggests, the phrase “inclusive teaching” lacks a seminal definition. However, in a recent survey of hundreds of U.S. faculty, Addy et al. (2021) asked what inclusive teaching meant to them and found that a central theme was creating equitable and welcoming classes where all students can succeed and feel a sense of belonging. Research over many decades shows that when students make social connections within their colleges and universities, they are more likely to persist to their degree (O’Keeffe, 2013). Students’ sense of belonging is connected to student persistence in the institution (Strayhorn, 2019) and is positively correlated with reported increase in time studying, communications with professors, and a greater increase in GPA over time (Walton & Cohen, 2011). Inclusive teaching is operationalized for the present study as how we mitigate the barriers that prevent students from succeeding in their courses and feeling a sense of belonging in the institution.

At our institution, a large R1 university in the Northeast, a range of opportunities existed for instructors to learn about how to make their classes more inclusive. However, as in many large institutions, silos and a lack of communication make it difficult to learn about these opportunities. Faculty also tend to gravitate to some strategies, such as Universal Design for Learning (UDL), while being unaware of others. For instance, faculty continue to consider accessibility such as alternative text for images or closed captioning for videos as compulsory instead of as strategies to promote inclusion for students. Recent scholarship argues accessibility training should be mandatory for instructors to promote inclusion and ensure all students are able to learn (Betts et al., 2013).

We found that instructors had a limited understanding of inclusive pedagogy and were not incentivized to seek out additional information. To address these challenges, our university-wide Center for Teaching and Learning developed a collaborative program to bring together many of the university’s experts on issues related to inclusivity in the classroom, provide and advertise a series of inclusive pedagogy workshops, and incentivize instructors to participate through a certificate program. The purpose of this study is to share one institution’s faculty development program intended to support inclusive teaching. After reviewing literature on faculty development of inclusive teaching and impediments to successful faculty development programs, we share the design of a program that overcomes these difficulties. This study examines whether a collaborative educational development series that supports inclusive classroom practices leads instructors to adopt inclusive teaching practices. In particular, we investigate whether participants understand the issues presented in the core competencies, whether participants used this knowledge to create more inclusive learning environments, and whether these new practices “stick” after the program is complete. We conclude with a discussion of next steps.

Background

Recognizing the importance of supporting inclusive and diverse learning environments, many institutions have begun to offer faculty development programming for inclusive teaching (Awang-Hashim et al., 2019; Campbell-Whatley et al., 2016; Erby et al., 2021; Hudson, 2020; O’Leary et al., 2020). This diversity and inclusion programming addresses different issues and, as a recent meta-analysis found, reflects a diversity of theoretical perspectives on how to create inclusive learning environments (Stentiford & Koutsouris, 2021). From this literature, we draw three broad themes that are all related to our working definition of inclusive teaching and inform the competencies we develop for our program: self-reflection, strategies for creating inclusive learning environments, and accessibility.

When instructors and students reflect on their own social and professional identities, they can better reflect on how to mitigate barriers to learning and student success (Applebaum, 2019; Bell et al., 1997; Berk, 2017). By addressing our own identities, biases, prejudices, and fears, as well as continually improving knowledge about the experience of bias and microaggressions, instructors can better identify the moments in which students may feel marginalization, discomfort, or even harm. Self-reflection plays a prominent role in literature on inclusive teaching, such as in O’Leary et al.’s (2020) immersive multi-day inclusive excellence workshop in which self-reflection allowed instructors to become more cognizant of students’ identities (see also Campbell-Whatley et al., 2016). Instructors who reflect on their students’ identities are also better positioned to recognize and prevent harm to students from overt bias, implicit bias, or microaggressions. Discriminatory experiences decrease students’ sense of belonging to their institution for both those targeted by discrimination and those who witness the behavior (Jackson et al., 2023). Microaggressions are correlated to students’ physical and mental health, stress, satisfaction, and school and work performance and are found to be at least as damaging as overt discrimination (Jones et al., 2016).

Another way for instructors to reduce barriers to learning is to adopt strategies for creating inclusive learning environments. These include using ice breakers to build community; learning the correct pronunciation of student names; using students’ correct pronouns; and adopting flexible course policies, strategies, and techniques to accommodate individual differences. Many institutions supporting instructors in inclusive pedagogy have focused on providing training on UDL (CAST, 2018). While many institutions focus on UDL to support students with disabilities (Lombardi & Murray, 2011), the changes instructors make are meant to provide support and scaffolding for all students (McGuire et al., 2003) including students with less thorough secondary education backgrounds, students who are not native speakers of English, first-generation students, and neurodiverse students. Chapman and Jackson (2021) found instructors were unprepared to implement UDL and did not visualize UDL as the iterative process it is intended to be, recognizing that not all barriers to learning can be anticipated. Indeed, these barriers may change with each new group of students in a course.

A third way for instructors to reduce barriers is through focusing on accessibility of course content. In a needs assessment for a training program, instructors said that lack of training on how to accommodate those with disabilities was one of their biggest obstacles to teaching in a more inclusive way (Moriña et al., 2020). Experts agree that accessibility training is necessary to provide instructors the knowledge to support students with disabilities (Betts et al., 2013), as do instructors themselves (Guilbaud et al., 2021).

With these programming goals in mind, we turn to the educational development literature to consider implementation. Educational development programming works best when programs make space for community building, encourage critical reflection and dialogue (Awang-Hashim et al., 2019), foster voluntary participation (Potthoff et al., 2001), and strengthen commitment to effective teaching while providing spaces to share successes (Xie & Rice, 2021). A faculty development design to support this is the use of communities of practice (CoPs), which have been found to be a successful model for faculty development (McNair & Veras, 2017). The limitation of the CoP model lies in the ability to scale, as these groups typically are small with a dozen or fewer participants (Awang-Hashim et al., 2019; Hakkola et al., 2021). Since our institution is large, we decided that the CoP model would be too challenging to scale in a way that would have a significant impact.

At the same time, a single day’s training session or workshop, while relatively easy to organize, would be unlikely to achieve our goals. Longer program offerings that span multiple days positively impact program efficacy (Hudson, 2020), and faculty development opportunities that extend over multiple days, weeks, or semesters also provide the chance for faculty to build a collegial sense of community (Xie & Rice, 2021). Given this research, we found that it was important to design a program that would link multiple workshops together into a series of workshops and activities that would encourage deep reflection and community building.

Topics as diverse as disability support, UDL, and open educational resources are typically supported by different units on a campus, which makes it hard for one unit (e.g., a teaching center) to provide a comprehensive support program. Instead, institutions should, as Gatlin et al. (2021) state, “recognize the wealth of knowledge [their] own campus has already cultivated for taking on large scale projects” (p. 60). Fortunately, teaching centers can have an important role in “leveraging existing campus resources” (Truong et al., 2016) through coordinating the work of other university offices and even bringing in external vendor programs (Brinthaupt et al., 2019). By creating partnerships among university offices and with expert teachers, minimally funded teaching centers can offer a variety of programming such as running regional or national conferences, support scholarship of teaching and learning, and run workshops series (Coria-Navia & Moncrieff, 2021). This cooperative model has great promise for inclusive pedagogy training given the divergent strands of DEI training.

Taking these studies into consideration, a Classroom Inclusivity Series program was designed for Rutgers University. We describe the program and research design to evaluate the program below.

Method

Program Design

Given our definition of inclusive teaching as adopting instructional measures that mitigate barriers to success and student learning and our review of the relevant literature, we developed three program competencies:

Competency 1: Understand and begin to address one’s own and one’s students’ identities, biases, prejudices, and fears and the impact they have on learning and the classroom environment.

Competency 2: Infuse inclusive teaching practices into one’s own educational practices by course re-design or adopting new teaching activities.

Competency 3: Ensure course content, web pages, activities, and assessments are accessible to all students.

We designed the program as a slate of individual workshops and discussions that were at least one hour in length offered over four months in late 2021. Sessions were developed and run by individual units that were brought together by the authors who sought out those across the institution who might support inclusive classroom environments. We learned about these units and engaged with them through liaising with our University Equity and Inclusion Office, which had surveyed the university to understand what work related to inclusive pedagogy was underway. All workshops aligned with one of the three competencies of the program.

While the workshop topics were vetted by the coordinating offices before being included in the program, each office was given creative freedom to develop the most appropriate training, so long as the session was interactive. Given the nature of the partnership between independent offices and centers, it was impossible to evaluate individual workshops and there was no overall quality assurance for the delivery of workshops, although individual offices evaluated their own presentations consistent with university standards. These partnering offices were recognized for their contributions by being listed as part of the initiative on the program website.

Nine workshops were offered for Competency 1, 15 for Competency 2, and 12 for Competency 3. Across all competencies, most workshops were offered just once or twice during the series. Table 1 provides a listing of the unique sessions offered and the unit that designed and gave them.

Workshops Included Within the Series

Workshop title |

Collaborating unit offering session |

|---|---|

Competency 1 |

|

Responding to Interpersonal Violence |

Center for Violence Prevention |

Microaggressions: Impact and Interventions |

Center for Violence Prevention |

Classroom Inclusivity Through Self-Awareness |

University-Wide Teaching Center |

Improving Education With the Science of Learning: The Impact of Culture & Beliefs |

University-Wide Teaching Center & Global Office |

Military Cultural Competency Education Session: Green Zone Training |

Veterans Affairs Office |

Facilitating Difficult Dialogues in the Classroom |

School Teaching Center & Anti-Racism Coalition |

Voices of Diversity: Returning to Campus |

School Teaching Center |

Voices of Diversity: Non-Traditional Students |

School Teaching Center |

Competency 2 |

|

Creating and Supporting Inclusive Learning Environments |

University-Wide Teaching Center |

Disability as an Aspect of Diversity: Understanding Access and Inclusion in the Classroom |

Office of Disability Services |

What Faculty Should Know About Office of Disability Services Accommodations |

Campus-Based Teaching Center |

Cultivating a Language and Social Justice Praxis: Reflection, Dialogue and Action for Social Change |

Social Justice Initiative |

Practical Approaches to Creating Inclusive, Equity-Oriented STEM Classroom Environments |

Department Session—outside speaker |

Designing Inclusive Course Syllabi |

Teaching Assistant Training Program |

Developing a Culturally Responsive Curriculum |

Office of DEI and Teaching Assistant Training Program |

Universal Design for Learning and Inclusive Teaching Strategies |

Teaching Technology Office |

Culturally Responsive Course Design and Teaching Strategies |

Teaching Technology Office |

Competency 3 |

|

Introduction to Accessibility |

Accessibility Office |

Content Accessibility 101 |

Accessibility Office |

Web Accessibility 101 |

Accessibility Office |

PowerPoint Accessibility |

Accessibility Office |

PDF Accessibility |

Accessibility Office |

Captioning 101 |

Accessibility Office |

Accessibility and Teleconferencing |

Accessibility Office |

Social Media Accessibility |

Accessibility Office |

Creating Accessible Online Content: Text, Documents, Images, and Video |

Teaching Technology Office |

Finding and Using Open Educational Resources for Your Courses |

Campus-Based Teaching Center |

Participants who attended at least one session under each competency and submitted three reflection statements describing what they learned and what instructional changes they might make were awarded a Certificate for Lifelong Learning in Inclusive & Equitable Teaching. The coordinating teaching center in partnership with the university office of diversity, equity, and inclusion reviewed the submissions and issued the certificate.

Research Design

An embedded sequential mixed methods study approved by Rutgers University Institutional Review Board was designed to help understand the short and long-term impacts of the program and the processes through which program outcomes are achieved (Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). Of the 82 individuals awarded the certificate, 50 consented to participate in the study. Participants completed a survey containing Likert-scale and open-ended questions at the end of the Fall 2021 semester. Focus groups were conducted in Spring 2022.

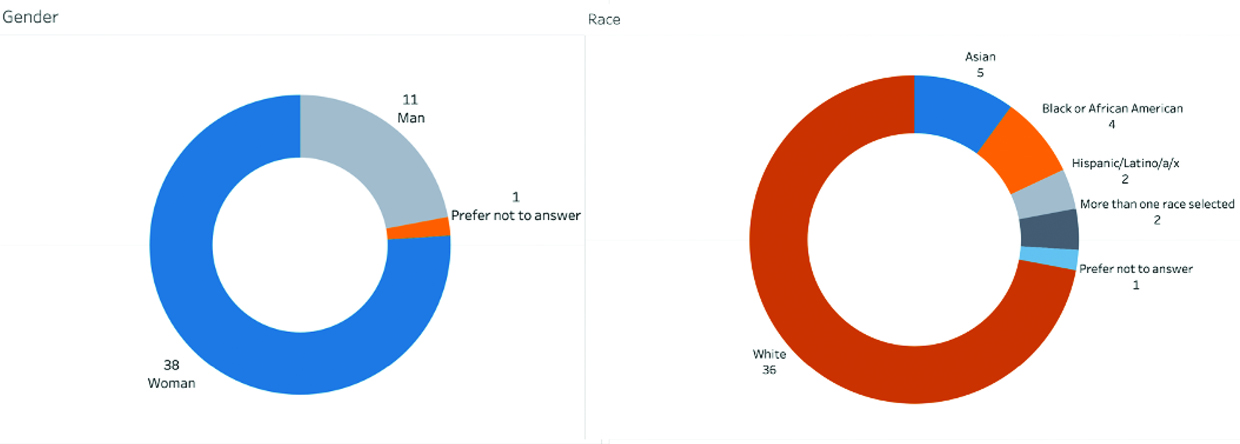

Participants represent 13 of the 29 schools at the institution, all campuses and non-academic units. Demographics are shown in Figure 1. The majority identified as women, and the modal race category was White. Both groups are overrepresented, as our faculty is slightly less than 50% White and more than 50% men. Note that none of the participants identified as genderqueer even though it was provided as an option on the survey.

Forty-one (82%) participants are primary instructors of for-credit or non-credit courses, four are teaching assistants or postdocs, three are staff with teaching or training responsibilities, and two had no teaching responsibilities. Teaching experience ranged from little to none to more than 30 years.

Survey, Self-Reflection, and Focus Group Prompts

The survey included semiquantitative (Likert-scale responses) and qualitative (open-ended survey responses) and was administered in Qualtrics (2022). Demographic questions asking participants to indicate school, department, teaching role, years of teaching experience, gender, and ethnicity were also included as in similar studies (Awang-Hashim et al., 2019; O’Leary et al., 2020). For each of the three program competencies, participants selected which workshop they attended and responded to open-ended reflection prompts.

Participants were provided the guidance that reflections should include (1) explanation of what ideas or techniques they learned from this workshop; (2) how they will use and/or adjust these techniques in their teaching; and (3) how implementation was received or challenges they anticipated during implementation. They were also provided the opportunity to upload or provide links to examples to support their reflection. As part of our review process for issuing certificates, research staff read each of the three reflections and rated participants’ understanding of the content, implementation, and reflective learning using three proficiency categories as seen in the rubric in Table 2. The reviewers met in advance and reviewed early submissions together to establish a shared understanding of the rubric criteria.

Rubric Used to Evaluate Participant Reflections

Evaluative criteria |

Proficient |

Developing |

Novice |

Not enough information |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Understanding of content |

Demonstrates an understanding of one or more key ideas or techniques learned in the workshop |

Demonstrates some understanding of key ideas or techniques, but discussion is superficial, incomplete, or factually inaccurate in places |

Does not convincingly demonstrate understanding of workshop content |

Not enough information |

Use of content |

Demonstrates that participant meaningfully planned to or has engaged with these ideas in a classroom context |

Indicate desire to make changes but changes are superficial, inadequately described, or instructor doesn’t commit to making changes |

Does not convincingly address plans to use content from a workshop |

Not enough information |

Reflective learning & practice |

Demonstrates a thorough and realistic reflection on the content and/or implementation of these concepts in the classroom context |

Reflects on content and/or implementation in a superficial way such as providing a critique with no discussion of solutions |

Does not convincingly reflect on implementation and/or content |

Not enough information |

Eight Likert-scale questions were included on the survey to evaluate participants’ knowledge and attitudes regarding the program level competencies. Three of these questions have been adapted from the Cultural Competence Self-Assessment for Teachers (Lindsey et al., 2018), two questions from the Teacher Efficacy for Inclusive Practices (Emmers et al., 2020; Sharma et al., 2012), and one question from the Inclusive Teaching Strategies Inventory (Lombardi & Murray, 2011). Two were designed by the research staff to address participant attainment of program competencies. The scales for all the questions are a 5-point Likert-scale of strongly agree to strongly disagree for consistency and to avoid participant confusion. The questions and which competencies they are designed to evaluate are provided in Table 3.

Description of Likert-Scale Questions

Question |

Evaluation of competency |

|

|---|---|---|

Q1 |

I know the effect that my culture, ethnicity, biases, and prejudices may have on the students in my classroom. |

1 |

Q2 |

I work to develop skills to manage and respond to conflict, bias, and microaggressions in a positive way. |

1 |

Q3 |

I know how to learn about people and cultures unfamiliar to me without giving offense. |

1 |

Q4 |

I am confident in my ability to create an inclusive learning environment for my students. |

2 |

Q5 |

Inclusive teaching practices were easy to implement in the course(s) I teach (taught). |

2 |

Q6 |

I am confident in my ability to incorporate more diverse points of view in my course curriculum. |

2 |

Q7 |

I believe it’s important to post electronic versions of course notes, handouts, and other materials that are accessible. |

3 |

Q8 |

The workshops provided me strategies to assist me in making my course site and materials accessible for all students. |

3 |

We understood that upon completing the reflections in the survey, participants may have only planned the inclusive teaching practices they would implement in the future, perhaps at the start of the next semester. The purpose of the focus groups was to elicit qualitative evidence of the inclusive practices that participants had implemented and the barriers they encountered during implementation. They were therefore scheduled several months after the end of the series. The survey contained a question asking participants if they would be interested in participating in a focus group during the Spring 2022 term. All 44 participants who indicated their interest with “yes” or “maybe” were contacted in March and asked to participate in focus groups in April or May. Three virtual focus groups were conducted by facilitators with a total of 14 participants (four to five in each group).

The focus group questions were designed by the research team and included questions about inclusive teaching practices, the series, and participant attitudes. For example, to learn about inclusive teaching practices, we asked, “How successful have you been in implementing the changes you wrote about in your reflection last year?” and “What are the most challenging inclusive teaching practices for you to maintain?” To learn about the series more broadly, we asked, “Did the certificate motivate you to attend these three sessions and engage more deeply than you would have otherwise?” and “How can the series be better?” We also asked, “Has the inclusive teaching series changed your attitudes toward diversity, equity, and inclusion?” We turned to each subsequent question when the participants had exhausted the conversation on the previous question and asked follow-up questions as needed. Focus groups were not recorded, but the anonymous transcript was saved, and facilitators took notes.

Analysis included basic descriptive statistics of mean, median, standard deviation, and frequencies of all Likert-scale questions. Distributions of responses were also calculated. Participants’ reflection statements were coded using an inductive process to determine what instructional techniques the participants adopted. We used NVivo software to keep track of the coding process (QSR International, 2020). Notes from focus groups were reviewed by both authors and used to understand and illustrate challenges with the series.

Results

Participant Understanding

Did participants understand the central concerns in the core competencies? Given the collaborative nature of the program, this question helps us understand whether most of the workshops, offered as they were by a variety of partners, effectively transmitted the central messages.

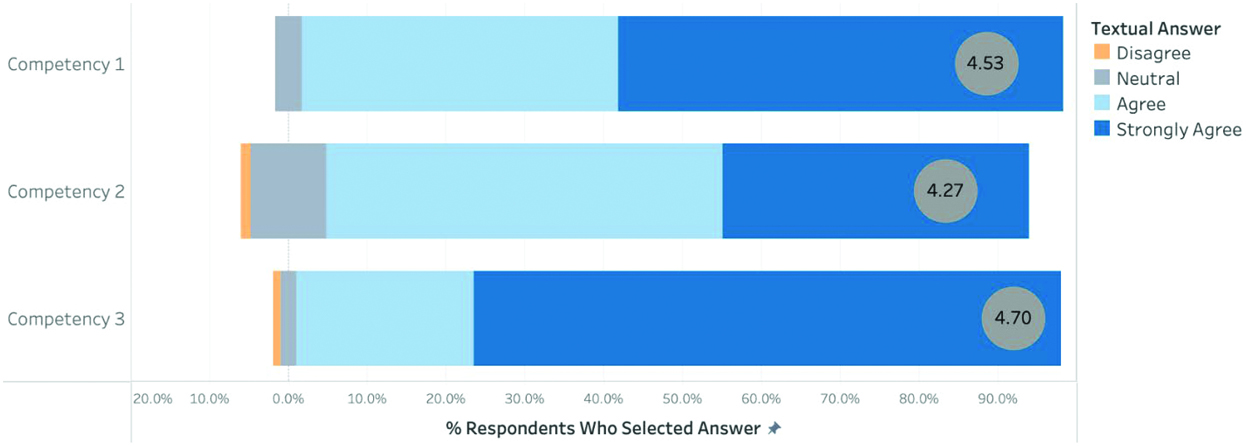

The Likert-scale questions were considered first, three of which were used to develop an index showing participants’ knowledge and attitudes of Competency 1. These were acknowledgment of the impact of culture and biases on students, developing skills to respond to conflict, and learning about unfamiliar people and cultures. Three items loaded into participant attainment of Competency 2 were confidence in creating an inclusive classroom, incorporating diverse points of view, and ease in implementing inclusive teaching practices. In Competency 3, two items loaded for the index were participant belief in the importance of ensuring course content is accessible and that workshops provided strategies to accomplish this. An initial analysis of the data indicated that participants’ knowledge and understanding of program competencies were generally high, as seen in Figure 2.

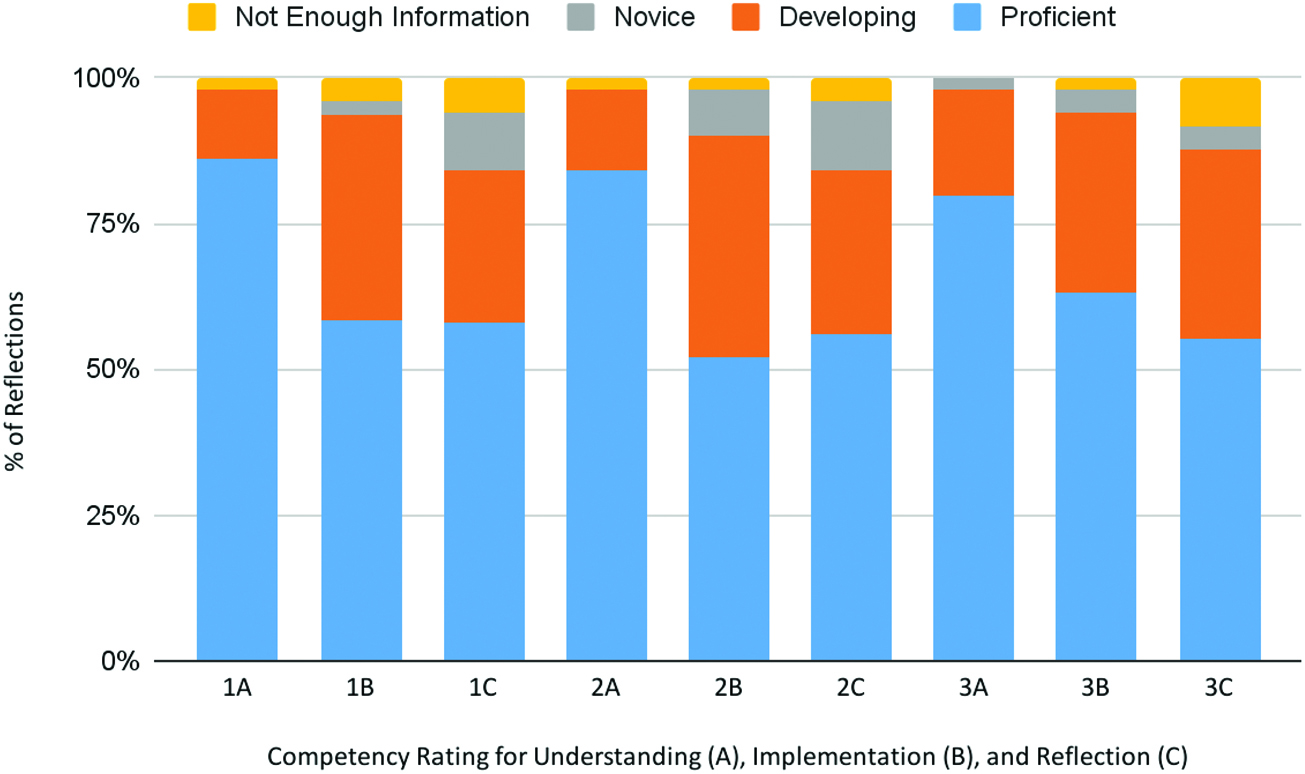

The design of the program did not permit a pre-post assessment, so while participants held attitudes that aligned with the competency, we cannot conclude this was due to the program. To explore this question, we used our qualitative evaluation of participant reflections on each of the competencies. Each of the three reflections were rated for understanding, implementation, and reflection. The distributions of participants who were rated proficient, developing, or novice for each of the criteria for each of the three competencies are seen in Figure 3.

As Figure 3 shows, most participants demonstrated an understanding of the content, with more than 75% of respondents marked as proficient in 1A, 2A, and 3A. Fewer (50%–60%) were marked as proficient in both their implementation of new instructional techniques and reflecting on the content. However, the majority of participants were marked as developing or proficient in each category, with few marked as novice or not enough information.

Taken together, this shows that, after attending the workshops, most participants expressed a proficient understanding of the program competencies, had a proficient understanding of how to implement instructional changes, and had reflected on the challenges of doing so.

Instructional Changes

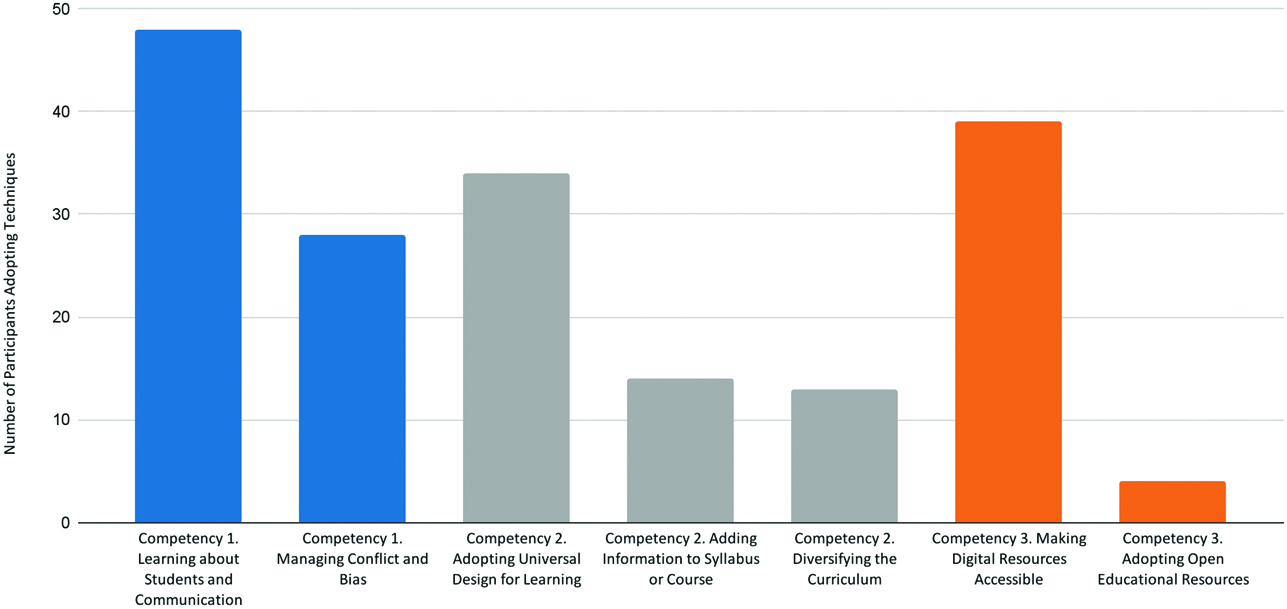

Do instructors plan to implement the instructional techniques they learned about in this program? In their reflection essays, instructors committed to adopting a variety of instructional strategies, drawn from the collection of possible strategies they learned about in the sessions they chose to attend. Figure 4 shows the frequency of different types of instructional changes to which participants committed.

Competency 1

From the workshops that focused on understanding and addressing one’s own and students’ identities, biases, prejudices, and fears, participants adopted instructional techniques related to learning about students and communicating with them in ways that make them feel more welcome and techniques for managing conflict and bias in the classroom.

For instance, instructors reported they would survey students or ask them to share about their identity at the beginning of a course. Instructors committed to learn and use student preferred names and pronouns and the proper pronunciation of names. Participants said they would consider language choices such as idioms, jargon, and examples that might not be accessible to all students. They vowed to build stronger student-student relationships so that students would also have ways to learn about one another. Less frequent, though still common, were various techniques for managing classroom conflict, incidents where bias was expressed, microaggressions, and other tense situations. These strategies include preventive measures such as developing shared classroom norm documents at the beginning of a course or using a microaggression inventory or similar tool as a teaching activity, as well as intervention or de-escalation strategies to manage conflict in the moment.

Competency 2

From workshops focused on inclusive teaching practices, instructors adopted teaching techniques and strategies related to UDL, adding new information to their course or syllabi, and diversifying the curriculum.

A majority of our participants described their intent to adopt techniques consistent with UDL. They said they would provide students with flexibility, agency, and choice; would help provide options for comprehension by organizing, chunking, or scaffolding material; and would include student voices and knowledge in the teaching process in order to improve a sense of community and make material relevant and engaging. Many participants shared long lists of UDL principles. Some instructors said that they would include additional information in the syllabus or in first class meetings. For example, they said they would include information about various support services available at the university, along with candid text about how students should use these resources. Others said that they would do more to provide information about the hidden curriculum in academia, the often-unexplained knowledge about how to navigate the academic world for those unfamiliar. For example, they said they would explain to students what “office hours” are and how to use them. Less frequently, participants also said that they would change their curriculum either by providing example and problem sets that borrowed from a wider variety of cultures or by changing readings to highlight other cultural perspectives and author backgrounds.

Competency 3

From the set of workshops that focused on ensuring that course content, web pages, activities, and assessments are accessible, participants mainly committed to making digital resources accessible. Participants described how they would make course content accessible by captioning videos; adding alternative text to images; formatting documents with accessible color choices, bolding, and headings; and appropriately displaying links. Participants often provided lists with several types of changes they would start making in courses. Lastly, some participants told us that they would adopt open educational resources such as open digital textbooks, articles that could be shared under fair use, and other open resources.

Taken together, this suggests that after participating in the program, instructors planned to implement meaningful course changes, at least at the time when they submitted their reflections. But did they follow through? We turn now to our focus groups to help address this point.

Follow-Through

From discussions with focus groups three to four months after the program completion, it was evident that enacting changes is not as easy as committing to adopting changes in a reflection statement. When we asked about progress on instructional changes, most focus group participants said that they had tackled the easiest changes first but would need more time to take on difficult or time-consuming instructional changes. For example, a couple of our participants said that they had implemented a survey to learn about student identities, and others mentioned that they had taken steps to make digital media accessible. Others seemed to have forgotten the instructional techniques to which they had committed and suggested that it was too difficult to make changes in the middle of an academic year. Overall, we got the sense that our participants had only partially achieved their goals.

To illustrate the challenge, a common barrier that most of the focus group participants discussed was the large amount of time and effort required to ensure documents and course content were accessible. Some participants wrote in their self-reflections that while it is plausible for them to make sure new content is accessible, it is tedious and time consuming to revise existing content to make it accessible. One of the focus group participants said that an incentive such as a course release or stipend would be helpful during the implementation phase due to the time requirements.

Taken along with other evidence, this suggests that the programming could do more to provide practical advice and logistics. Participants rated the survey question that asked if inclusive teaching practices were easy to implement in their courses, the lowest of all questions with a mean of 3.98 out of 5. In our analysis of participant reflections, only 50%–60% of participants were marked as proficient in implementation of the competencies. Comments from a focus group may help explain this. One participant said that the sessions should include tangible practices that were clear, practical, and easy to implement. Others asked for concrete instructions on how to make documents, PowerPoint presentations, and videos accessible and for “workshopping” sessions in which faculty develop a product of some sort for immediate instructional use.

Discussion

The program evaluation demonstrated that most participants exhibited an understanding of the program competencies and committed to adopting inclusive teaching practices. The program had a wide reach, with 82 participants from around the institution earning a certificate in the first year it was offered. At the same time, the partnering offices holding sessions reported an influx of attendance. It has driven interest toward diversity, equity, and inclusion programming. Despite these successes, the evidence we gathered suggests that we can improve the series by developing additional opportunities for community building and self-reflection, finding ways to re-engage early adopters, and developing better incentives to motivate more instructors to participate.

Opportunities for Self-Reflection and Community

We wanted participants to reflect on the impact of their identities, biases, prejudices, and fears on the classroom environment because self-reflection is an essential part of being prepared for instructional challenges (Applebaum, 2019; Bell et al., 1997; Berk, 2017). Yet reviewers rated the reflection statements lower on self-reflection than knowledge. Our focus group participants said that they wished there had been more time in workshops to practice self-reflection, meet other practitioners, and develop community. Focus group participants told us that connecting with colleagues across the institution was a valuable part of the program for them, as we would expect from literature on faculty development programming (Awang-Hashim et al., 2019; Erby et al., 2021; Potthoff et al., 2001; Xie & Rice, 2021). As one focus group participant said, they valued the connections with other faculty with whom they “would have never crossed paths.”

For these reasons, the next iteration of our program is being planned to support self-reflection and community building by adding a required discussion group to support Competency 1. These small group discussions will be facilitated by educational developers employing a facilitation guide that prompts participants to reflect on and share their experiences. Participants will be encouraged to respond to others and build on common themes together. This new discussion group should not only promote self-reflection but also support community building and networking.

Engagement Opportunities for Early Adopters

One of the challenges of running a yearly program is that many of the most passionate instructors complete the program in the first year and thus may not continue attending workshops. At the same time, we learned from focus groups that participants needed more encouragement to implement the practices to which they committed in their reflections. Several focus group participants asked for ways to stay involved as the program continued. We hope that those who earned a certificate during the pilot year, the early adopters, can create a network to help facilitate the spread of the initiative (Rogers, 2003).

Our solution is to include in future iterations of the program advanced Level 2 and Level 3 certificates to those who implement inclusive teaching practices. Instructors who have already received the Level 1 Certificate can choose one of the three competencies to focus on implementing. They will meet with series facilitators to connect them with resources and ensure their project is feasible within the time frame. After implementing changes, these instructors will produce a description that details their process and course changes to share with the university community. A third level is also under development, which will focus on instructors sharing their process of implementation with others to continue to engage early adopters and other faculty around the university.

Moving Beyond “The Willing”

How do we begin to engage those instructors who did not participate in the program the first semester? Participants who engaged in the sessions and the certificate process represented varied units across the institution, but this group remains a small percentage of the total instructional faculty of the university. Furthermore, many of our participants were among the most active and engaged faculty and had already shown interest in inclusive pedagogy. The certificate that we offered, while a motivating incentive for the instructors who completed the program (they told us as much in focus groups), could be more effective if matched with institutional commitments to the program.

Because instructors juggle various responsibilities including research, teaching, service, and their personal commitments (Scherer et al., 2020; Taylor & McQuiggan, 2008), institutions must value and reward inclusive teaching programming to drive participation. Focus group participants told us that while committed to the goals of the program, the certificate prompted them to engage more deeply than they would have otherwise, by ensuring they made time to attend and reflect on sessions from all three competencies. But they also explained the need to bring together full departments for conversation and dialogue around these topics to create shared values and understanding. They specifically mention the need to incorporate these values within promotion and tenure processes. We understand this to be an important move, but within our institution rewarding inclusive teaching in promotion and tenure is beyond the scope of the project.

Some deans promoted the program to their faculty by acknowledging participation and providing incentives, measures that focus group participants told us were effective. For example, one dean had brought everyone who had earned a certificate out to lunch and announced their success at a faculty meeting. These instructors told us that this encouragement convinced them to prioritize earning the certificate and that they appreciated being recognized for their efforts. Targeted, personalized outreach to school administration explaining this outcome and a request to promote the series to faculty will be incorporated into the next iteration of the program.

Conclusion

We hoped that participants in the Classroom Inclusivity Series would learn about the three competencies and would use this knowledge to make instructional changes that mitigate barriers to student learning and success. Our assessment of the program, carried out through examining self-reflection statements, speaking with participants, and analyzing survey results, revealed that participants rated their knowledge of the three competencies highly and that they committed to using a variety of instructional strategies, even as implementation was more difficult. Still, assessment was limited by a lack of pre- and post-measures showing participant learning and measures of implementation fidelity of workshops.

The programming covered many aspects of inclusive teaching, but there are numerous opportunities to expand programming to deliver a more comprehensive set of workshops and presentations. This is especially true regarding workshops to help us understand our students, because student identities are varied and intersectional. The certificate process we enacted in the first year was effective, but it too can be expanded to help us retain instructors who have already committed to these efforts and help scale the program for wider reach in the future. Institutional support is also a necessary component of reaching a wider audience and building momentum over time.

This case study provides evidence that smaller centers of teaching and learning in decentralized institutions can provide effective faculty development by coordinating programming between various offices and issuing certificates as an incentive for those who participate in programming. Would this model work in other institutions? One of the advantages as a large regional institution is that there are many offices providing support for teaching. We didn’t have to deliver every workshop. Still, we suspect that most institutions do have experts in-house that could provide training on many of these topics, even if there are fewer offices to accomplish it, though it might be most beneficial in large institutions like ours.

Biography

Christopher R. Drue is the Associate Director of Teaching Evaluation at the Office of Teaching Evaluation & Assessment Research (OTEAR) at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. He is responsible for helping schools and departments develop robust, meaningful, and useful methods of evaluating teaching, reports on teaching effectiveness at Rutgers, and offers workshops and programs to support effective teaching strategies.

Christina A. Bifulco is the Associate Director for Teaching and Learning Analytics at the Office of Teaching Evaluation & Assessment Research (OTEAR) at Rutgers, the State University of New Jersey. Her primary responsibility is supporting instructors, schools, and departments in the development and analysis of meaningful measures that provide actionable data to understand and improve instruction at the university.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the contributions to our program from our partnering offices who made our collaborative inclusive teaching program possible. We especially appreciate Dr. Monica Devanas, Dr. Barbara Bender, Dr. Corinne Castro, and Dr. Mary Emenike, as well as our anonymous reviewers who provided invaluable early feedback on our program evaluation.

References

Addy, T. M., Dube, D., Mitchell, K. A., & SoRelle, M. (2021). What inclusive instructors do: Principles and practices for excellence in college teaching. Stylus Publishing.

Applebaum, B. (2019). Remediating campus climate: Implicit bias training is not enough. Studies in Philosophy and Education, 38(2), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9644-1https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-018-9644-1

Awang-Hashim, R., Kaur, A., & Valdez, N. P. (2019). Strategizing inclusivity in teaching diverse learners in higher education. Malaysian Journal of Learning and Instruction, 16(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2019.16.1.5https://doi.org/10.32890/mjli2019.16.1.5

Bell, L. A., Washington, S., Weinstein, G., & Love, B. (1997). Knowing ourselves as instructors. In M. Adams, L. A. Bell, & P. Griffin (Eds.), Teaching for diversity and social justice (pp. 299–310). New York: Routledge.

Berk, R. A. (2017). Microaggressions trilogy: Part 3. Microaggressions in the classroom. Journal of Faculty Development, 31(3), 95–110.

Betts, K., Welsh, B., Hermann, K., Pruitt, C., Dietrich, G., Trevino, J. G., Watson, T. L., Brooks, M. L., Cohen, A. H., & Coombs, N. (2013). Understanding disabilities & online student success. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Networks, 17(3), 15–48. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v17i3.388https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v17i3.388

Brinthaupt, T. M., Cruz, L., Otto, S., & Pinter, M. (2019). A framework for the strategic leveraging of outside resources to enhance CTL effectiveness. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 38(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0038.104https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0038.104

Campbell-Whatley, G. D., Merriweather, L., Lee, J. A., & Toms, O. (2016). Evaluation of diversity and multicultural integration training in higher education. Journal of Applied Educational and Policy Research, 2(2), 1–14.

CAST. (2018). The UDL guidelines (Version 2.2). http://udlguidelines.cast.orghttp://udlguidelines.cast.org

Chapman, L. A., & Jackson, A. M. (2021). Accessibility matters: Universal Design and the online professional practice doctorate. Impacting Education: Journal on Transforming Professional Practice, 6(3), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.5195/ie.2021.184https://doi.org/10.5195/ie.2021.184

Coria-Navia, A., & Moncrieff, S. (2021). Leveraging collaboration and peer support to initiate and sustain a faculty development program. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.970https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.970

Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2011). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

Emmers, E., Baeyens, D., & Petry, K. (2020). Attitudes and self-efficacy of teachers towards inclusion in higher education. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 35(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1628337https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2019.1628337

Erby, K., Burdick, M., Tutwiler, S. W., & Petersen, D. (2021). Motivation to “keep pushin’ ”: Insights into faculty development facilitating inclusive pedagogy. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 40(2). https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.461https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.461

Gatlin, A. R., Kuhn, W., Boyd, D., Doukopoulos, L., & McCall, C. P. (2021). Successful at scale: 500 faculty, 39 classrooms, 6 years: A case study. Journal of Learning Spaces, 10(1), 51–62.

Guilbaud, T. C., Martin, F., & Newton, X. (2021). Faculty perceptions on accessibility in online learning: Knowledge, practice and professional development. Online Learning, 25(2), 6–35. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v25i2.2233https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v25i2.2233

Hakkola, L., Ruben, M. A., McDonnell, C., Herakova, L. L., Buchanan, R., & Robbie, K. (2021). An equity-minded approach to faculty development in a community of practice. Innovative Higher Education, 46(4), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09540-8https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-020-09540-8

Hudson, N. J. (2020). An in-depth look at a comprehensive diversity training program for faculty. International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 14(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2020.140103https://doi.org/10.20429/ijsotl.2020.140103

Jackson, Z. A., Harvey, I. S., & Sherman, L. D. (2023). The impact of discrimination beyond sense of belonging: Predicting college students’ confidence in their ability to graduate. Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice, 24(4), 973–987. https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120957601https://doi.org/10.1177/1521025120957601

Jones, K. P., Peddie, C. I., Gilrane, V. L., King, E. B., & Gray, A. L. (2016). Not so subtle: A meta-analytic investigation of the correlates of subtle and overt discrimination. Journal of Management, 42(6), 1588–1613. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313506466https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206313506466

Lindsey, R. B., Nuri-Robins, K., Terrell, R. D., & Lindsey, D. B. (2018). Cultural proficiency: A manual for school leaders (4th ed.). Corwin Press.

Lombardi, A. R., & Murray, C. (2011). Measuring university faculty attitudes toward disability: Willingness to accommodate and adopt Universal Design principles. Journal of Vocational Rehabilitation, 34(1), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-2010-0533https://doi.org/10.3233/JVR-2010-0533

McGuire, J. M., Scott, S. S., & Shaw, S. F. (2003). Universal design for instruction: The paradigm, its principles, and products for enhancing instructional access. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 17(1), 11–21.

McNair, T. B., & Veras, J. (2017). Committing to equity and inclusive excellence: Intentionality and accountability. Peer Review, 19(2), 3–4.

Moriña, A., Perera, V. H., & Carballo, R. (2020). Training needs of academics on inclusive education and disability. SAGE Open, 10(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020962758https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020962758

O’Keeffe, P. (2013). A sense of belonging: Improving student retention. College Student Journal, 47(4), 605–613.

O’Leary, E. S., Shapiro, C., Toma, S., Sayson, H. W., Levis-Fitzgerald, M., Johnson, T., & Sork, V. L. (2020). Creating inclusive classrooms by engaging STEM faculty in culturally responsive teaching workshops. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(32), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00230-7https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00230-7

Potthoff, D., Dinsmore, J. A., & Moore, T. J. (2001). The diversity cohort—A professional development program for college faculty. The Teacher Educator, 37(2), 145–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730109555288https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730109555288

QSR International. (2020, March). NVivo. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/homehttps://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

Qualtrics. (2022). Qualtrics XM. https://www.qualtrics.comhttps://www.qualtrics.com

Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press.

Scherer, H. H., O’Rourke, M., Seman-Varner, R., & Ziegler, P. (2020). Coteaching in higher education: A case study of instructor learning. Journal of Effective Teaching in Higher Education, 3(1), 15–29. https://doi.org/10.36021/jethe.v3i1.37https://doi.org/10.36021/jethe.v3i1.37

Sharma, U., Loreman, T., & Forlin, C. (2012). Measuring teacher efficacy to implement inclusive practices. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 12(1), 12–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.xhttps://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-3802.2011.01200.x

Stentiford, L., & Koutsouris, G. (2021). What are inclusive pedagogies in higher education? A systematic scoping review. Studies in Higher Education, 46(11), 2245–2261. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1716322https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1716322

Strayhorn, T. L. (2019). College students’ sense of belonging: A key to educational success for all students. Routledge.

Taylor, A., & McQuiggan, C. (2008). Faculty development programming: If we build it, will they come? EDUCAUSE Quarterly, 31(3), 28–37.

Truong, M. H., Juillerat, S., & Gin, D. H. C. (2016). Good, fast, cheap: How centers of teaching and learning can capitalize in today’s resource-constrained context. To Improve the Academy: A Journal of Educational Development, 35(1), 180–195. https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20032https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20032

Walton, G. M., & Cohen, G. L. (2011). A brief social-belonging intervention improves academic and health outcomes of minority students. Science, 331(6023), 1447–1451. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198364https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1198364

Xie, J., & Rice, M. F. (2021). Professional and social investment in universal design for learning in higher education: Insights from a faculty development programme. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(7), 886–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1827372https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1827372