Academic change work is increasingly a constituent of the work of educational developers and centers for teaching and learning (CTLs) (Kim & Maloney, 2020; Timmermans, 2014; Weston et al., 2017). In her study of 100 CTL missions, Schroeder (2011) finds that “change; innovation” is cited in nearly a quarter (22%) of CTL aims—and recent research suggests that this proportion has grown over the decade since (Wright, 2023). CTLs are key sites of individual and organizational transformation in higher education, particularly around teaching and learning (Kim & Maloney, 2020; Schroeder, 2011).

However, in embodying an academic change role, it is critical to be intentional and strategic. Moreover, that intentionality and strategy must take into consideration participatory decision-making practices. Others have found that explicit theories of change best enable effective organizational transformation (Kezar et al., 2015). As defined by Reinholz and Andrews (2020), a “theory of change” is “a series of hypotheses about how change will occur” (p. 3), explaining a driving mechanism or hypothesis about how outcomes can be achieved. Another related and helpful conception of a theory of change is “a predictive assumption about the desired changes and the actions that may produce those changes. Putting it another way, ‘If I do x, then I expect y to occur, and for these reasons’ ” (Connolly & Seymour, 2015, p. 2, italics in original). While many change agents have implicit theories of change, the deliberate articulation of these strategies can help us better achieve key goals (Kezar et al., 2015).

Connolly and Seymour (2015) provided several examples of theories of change from STEM education grants. For example, for the National Science Foundation Course, Curriculum, and Laboratory Improvement (CCLI) grants, these researchers noted assumptions that STEM improvement should begin with grassroots efforts and that the creation of new evidence-based materials will develop faculty capacity and allow the initiative to scale through subsequent adoption. As another illustration, they indicate that the Systemic Changes in the Undergraduate Chemistry Curriculum predicts that instructors will be more likely to adopt new methods if they are presented in a hands-on environment by peers.

Reinholz and Andrews (2020) helpfully distinguished a theory of change from change theory, noting that the latter is a framework of ideas, supported by evidence, with examples such as department action teams (Reinholz et al., 2020) or the four frames model of organizational change (Bolman & Deal, 2008). Other examples might be a micro/meso/macro lens (Takayama et al., 2017). While we focus solely on theories of change here, it is important to note that we differ from Reinholz and Andrews’s (2020) understanding that while change theories are “generalizable beyond a single initiative,” theories of change apply only to a “single change initiative” (p. 2). Instead, we rely on more foundational conception of theories of change, by the Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change (ActKnowledge and Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change, 2003, p. 4, italics in original), which noted, “Theories of change are often used for single programs . . . . However, a strength of the theory of change approach is that it can be used for initiatives that may comprise many programs and partners.” Here, we argue for the utility of developing a theory of change on the level of a CTL and describe the process through which we developed our own theory of change.

Although there is an emerging literature about the importance of explicit theories of change, particularly in STEM education reform (Connolly & Seymour, 2015; Kezar et al., 2015; Reinholz & Andrews, 2020), there is little work at this time about CTLs and theories of change. This absence is striking in light of the growing literature about the important role of educational development in academic change.

Many CTLs have missions, visions, and/or goals, which can be descriptive of “what you do all day, every day, as simply part of doing what you do” (Cruz et al., 2020, p. 63) or forward-looking, defining what the organization wants to be in the future (Özdem, 2011). However, while these documents often include implicit elements of theories of change, we argue that it is useful for a CTL to articulate them separately, if only to engage in the discussion. As Reinholz and Andrews (2020) noted, “The process of creating the theory of change allows a team to reach consensus on its underlying assumptions” (p. 2). In an examination of over 100 CTL annual reports, Wright (2023) found that while all CTLs reported some outcome of their work, none described their theory of change. (One center noted that it had a theory of change but did not say what it was.) One published example of a CTL theory of change (that the authors also refer to as a “logic model”) can be found in Miller-Young et al. (2021). This diagram presents 16 programs and services and links them to 13 intended short-term outputs, 10 medium-term outcomes, and five long-term institutional impacts.

Here, we describe a narrative process for CTL staff to adapt to their own contexts, to help further the development of theories of change. For STEM higher education change efforts, Reinholz and Andrews (2020) described a process for teams to diagram long-term outcomes, preconditions of those outcomes, and particular interventions used to drive these mechanisms. While this approach may be helpful for some CTLs, particularly those involved in creating a theory of change for a specific project or grant submission, we also imagine that alternatives are helpful, especially given the complex character of CTLs as organizations. For example, as organizations, CTLs often support multiple key goals and constituencies, balancing between positional leadership (administration) and grassroots leadership (faculty and students), to support institutional aims yet also push for institutional change (Little & Green, 2012; Wright, 2023). This complexity may mean multiple iterations or articulating multiple theories of change, as suggested by Kezar (2018).

The process we describe below represents a first attempt at one CTL’s development of a theory of change. For context, the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning at Brown University has approximately 45 full-time employees, serving a research university campus with over 1,600 faculty, almost 300 postdoctoral scholars, nearly 2,700 graduate students, and over 7,000 undergraduates. An anchoring philosophy of the student learning and faculty teaching experience is the University’s Open Curriculum, which is premised on values of self-direction, choice, and connection.

The Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning is well-established, with over 35 years in existence. However, like many CTLs (Kelley et al., 2017; Wright, 2023), it recently has been engaged in a series of integrations. These most recently took place with the university’s digital learning teams, but other integrations have involved student learning-focused units. (The authors represent multiple spheres of work of the center, including assessment, learning design, administration, and multilingual learning.) Because of these varied work cultures and values, the executive director believed that it would be helpful for the organization’s identity to discuss and develop a center-wide theory of change.

Below, we describe our process, outcomes, and potential applications. We then make recommendations for other CTLs who wish to create (or revise) a theory of change. We offer our experience in the spirit that by articulating our end goals (e.g., equitable student learning) and the key vehicles hypothesized to best achieve these aims (e.g., a course design institute, scholarship of teaching and learning [SoTL]), CTLs make it more likely that they will affect change. Below, we describe a three-stage process that the Sheridan Center found useful to develop a theory of change: (1) reflective idea generation at a retreat; (2) small-group refinement of ideas; and (3) full-group discussion, refinement, and consensus. Although our theory of change is new to the center, we end with some initial applications and speculate on other impacts.

Process

For a new CTL, foundational philosophies of its work—mission, visions, values, guidelines, and goals—can be challenging genres to author. Therefore, Wright (2023) argued that it can be helpful to start with a theory of change, which can be an anchoring thread for all of these statements of purpose. For inspiration, we began with the hub, incubator, temple, sieve (HITS) framework, which is defined in the POD Network (2018) guide, Defining What Matters, and borrows (liberally) from an article in the sociology of higher education authored by Stevens et al. (2008). Defining What Matters establishes four metaphorical orientations, or strategies, that a CTL might utilize:

Hub: To act as an organizational connector, promoting dialogue and collaboration across campus (e.g., through centralization of resources or cross-disciplinary learning communities)

Incubator: To foster growth of individuals or their projects (e.g., through orientations or mentoring programs or small grants)

Temple: To provide a space for recognition and reward (e.g., through teaching awards or academies or recognition programs such as Thank-a-Prof)

Sieve: To promote evidence-based practice and offer expertise (e.g., through SoTL programs or having the CTL publish its own scholarship of educational development research)

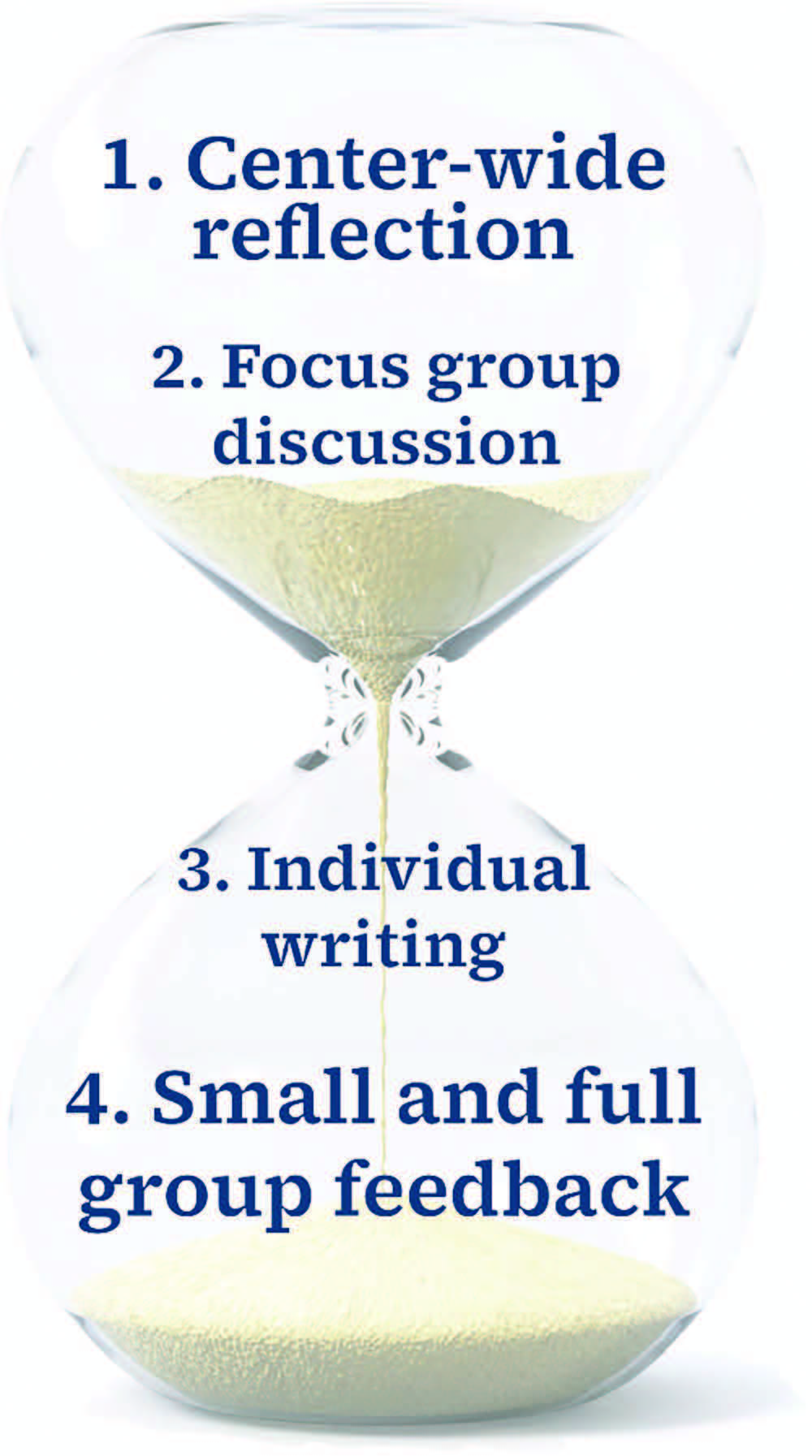

The theory of change statement was developed through a four-stage process, which included center-wide reflection, small-group discussion, individual writing, and small- and full-group feedback.

Center-Wide Reflection

The first step for the Sheridan Center’s theory of change development process was an all-center retreat. This stage involved all members of the center staff (40) and took around an hour.

Write-Pair-Share

First, in a write-pair-share activity, staff individually reflected on an area of their position description, which they believed to have most impact, using the sentence frame “If I [verb], then I expect [outcome] to occur, because [rationale].” This structure borrows from Connolly and Seymour’s (2015, p. 2) definition of a theory of change. A sample response is provided here: “If I [spotlight faculty] in a program, then I expect [more faculty will attend and be engaged] because [faculty will be motivated by community and engaged by peer-to-peer learning].” In pairs, we collaboratively reflected on the implicit views within our individual theories, to challenge and reformulate them into explicit theories of change (Kezar et al., 2015).

Four Corners Exercise

After a presentation of the HITS framework by the third author, all participants were invited to engage in a “four corners” activity. All staff were asked to identify one of the four HITS orientations (i.e., hub, incubator, temple, sieve) as the most important collective strategy for doing its work, in reference to the individual responses and the center’s mission statement (Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, n.d.). From these four corners, we engaged in an open discussion of our rationale for identifying each orientation.

Padlet

After discussion, each individual was invited to contribute a statement for a theory of change for the center, adding this to a Padlet. The Padlet was organized into four columns—Hub, Incubator, Temple, Sieve—and each staff member chose one metaphor to locate their statement. Example statements are provided:

Sieve: “If we demonstrate examples of how best practices and quality standards inform course design and facilitation in exemplar courses, faculty will be better able to apply these practices to their process because the output will be more tangible than hypothetical.”

Hub: “If the Sheridan Center provides a place where all learners can grow, then we expect more opportunities for the Brown community to connect across disciplines, departments, and roles because of our shared value of learning and being in dialogue.”

Small-Group Discussion

Next, a committee of six staff members (self-selected) and the third author convened to review the themes and draft statements generated during the all-staff retreat. The ultimate goal of this synchronous online discussion was to distill these disparate perspectives into a single theory of change. To that end, the committee split into two breakout sessions; each subgroup considered two of the orientations identified in the HITS framework and attempted to incorporate the relevant themes into a single theory of change statement. One group focused on reconciling the themes associated with hub and temple while the other took on those associated with sieve and incubator. These pairings were made to combine an orientation that had proved highly generative during the center-wide discussions (hub, incubator) with one that had generated fewer themes or ideas (temple, sieve). Each group documented their notes and reflections in a shared document.

Upon reconvening, staff shared the key takeaways from their small-group discussions and the theory of change statements they had generated, if applicable. The key themes identified by each subgroup are listed in the Appendix.

In the time allotted, only one group was able to draft a provisional theory of change statement. This proved unexpectedly beneficial for the full-group discussion: rather than attempting to reconcile two fully developed sentences, the focus group members considered how the unique themes generated by Group 1 might be incorporated into Group 2’s draft. In comparing notes, committee members were struck by how much overlap there was between the themes corresponding to different orientations. The center director (third author) took notes of the most important issues raised by both groups:

-

Common Themes:

Community

Focus on relationships and trust

Exploration, experimentation, innovation

Evidence-based

Supportiveness (a supportive environment)

Relationship-rich environment that crosses common boundaries

Community of expert practitioners

Individual Writing

To further refine the statement, one of the participants (first author) volunteered to review the meeting notes from the subgroup and plenary discussions in order to draft a unified theory of change statement to circulate back to the focus group and, eventually, to the center as a whole. This staff member essentially followed the same process as the small-group discussion, using Group 2’s provisional statement as a template to incorporate the themes emphasized in the plenary discussion (see above).

During the previous phase, the committee had considered whether the theory of change might include several sentences or incorporate bullet points or other forms of listing. Ultimately, the committee felt that it was important to keep the statement to a single sentence. Not only would this be more impactful rhetorically, it would also communicate a unified vision of the CTL’s transformative impact on campus. This was particularly important given the context of a large CTL housing several disparate work groups (or “hubs”) with varied roles and responsibilities. However, this format posed a challenge during the individual writing process, as it was necessary to synthesize many ideas into a single sentence. The task was made easier by thinking about the rationale (i.e., the [because] statement) as consisting of several mechanisms, or clauses, separated by commas. These clauses correspond to many of the major themes identified in the small-group discussion.

Generating the [if] and [then] statements proved more challenging: multiple clauses would add specificity and nuance but ultimately render the sentence cumbersome and difficult to parse. For this reason, the writer (first author) decided to keep the [if] and [then] statements more abstract, to harmonize with any and all rationales identified in the [because] statement. Ultimately, the all-staff discussion, focus group, and individual writing culminated in the following draft theory of change statement:

As a final check before sharing the draft more widely, the writer cross-referenced each major theme identified by the focus group with the corresponding section of the change statement, to ensure that everything had been included.If we create inclusive, supportive teaching and learning communities, we expect educators and learners to thrive because they will have the resources and opportunity to develop their expertise, pursue evidence-based practices, generate new innovations, and foster interdisciplinary and intergenerational relationships built on trust.

Member Checking

The draft was first shared with small-group discussion representatives, who endorsed it, before it was circulated center-wide by email in advance of a monthly all-staff meeting. During this meeting, the writer presented the focus group and drafting processes to colleagues before facilitating a group discussion to elicit feedback. On the whole, colleagues were satisfied with the draft and excited about its potential to shape the CTL’s work. Colleagues were curious about the relationship between the theory of change and its existing mission, vision, and values statements. It was important to all staff that these statements be in alignment. While the process involved alignment with the mission statement (during idea generation and the drafting process), after the all-staff meeting, the first author cross-referenced the theory of change with the vision statement and found them well aligned. The writer recirculated the draft to all staff, along with the mission, vision, and values statements, and invited colleagues to provide additional feedback within a two-week period. None was provided, and the statement was adopted and posted in the center’s annual report and website.

Discussion and Recommendations

As discussed, the unique nature of CTLs necessitates an approach to change theory that accommodates the fact that they often support multiple key goals and constituencies (Beach et al., 2016; Schroeder, 2011). With this in mind, the center developed a four-stage process for developing a theory of change that was inclusive and iterative, meaning the process contained multiple phases involving participants from all units within the center. Using multiple phases to craft the theory of change helped to ensure that all participants affected by the statement could have a chance to influence its creation, engaging, in other words, in participatory decision-making. During each stage of the process they were asked if they felt their concerns or questions had been addressed.

Bell and Reed (2022) described participatory decision-making as the process by which people influence the decisions that affect their lives. The results of this process depend, they noted, on its inherent integrity and inclusivity. Models of participatory decision-making processes vary, but they share some commonalities: epistemological flexibility that can accommodate contributions from differing knowledge bases; authenticity; transparency; agency, meaning one has access to resources necessary to participate; representation; and the ability to deliberate (Bell & Reed, 2022). Bell and Reed also found that accountability and feedback loops that “keep people informed about how their knowledge is being used” further create a sense of participant empowerment (p. 609). Finally, flexibility helps the entire process hold together: “Processes that lead to empowerment are characterized by their ability to adapt to the stage of the process,” they wrote, “as contexts [time, objectives, social-cultural contexts, political-governance contexts, and power dynamics] change over time or when they are applied in new and different contexts” (p. 609).

As a metaphor for this ideal participatory decision-making process, Bell and Reed (2022) chose a tree because, as they note, a tree can easily be pruned or trained depending on the needs of the process. Furthermore, the metaphor is simple enough to be useful yet complex enough to have power. It is rooted in the values of creating a safe space, promoting an inclusive process, and removing barriers. It takes into consideration the general atmosphere of history, power, process, culture, and politics. And, in the branches of the process itself, it promotes deliberation, representation, equality, authenticity, transparency, agency, and values. Finally, it builds in a canopy of accountability and feedback to ensure the decisions made continue to benefit those for whom they were made.

The center’s process likewise allowed for flexibility, inclusivity, and accountability. In addition to a tree, the center’s process could also be represented by an hourglass (Figure 1). This is because it incorporated center-wide reflection, focus group discussion, individual writing, and small- and full-group feedback, thereby going from large-group discussion to smaller group and individual editing and then back again to the large group for review. By following such an inclusive model of the participatory process, the center was able to develop a theory of change that resonated with all participants.

But was the statement novel and distinct enough from existing statements of purpose (e.g., mission, vision) to have utility? This was an additional consideration. In addition to hewing to participatory decision-making processes, the center had to make sure participants were not unduly limited by existing mission and vision statements and that they also developed an approach that aligned with these institutionally approved texts. During the center-wide retreat, participants were informed of the unique nature of theories of change. Emphasis was placed on how they differ from mission and vision statements. It was explained how theory of change statements are conditional and hypothetical and are therefore not as unequivocal and direct as mission statements. But they are also not unlike mission statements; they, too, can direct and shape action. They therefore occupy an interstitial space. In many ways, theory of change statements are in line with the organic and dynamic nature of teaching and learning centers in general, the goal of which is to support and be sensitive to the ever-changing needs of their constituencies (Felten et al., 2007).

With this in mind, the center made the process for developing its theory of change both receptive to the needs of participants as well as suggestive enough to encourage participants to think broadly about the center’s work. During the initial meeting, facilitators encouraged participants to think of the center in terms of the sieve, incubator, temple, hub framework, an approach that introduced a new way of thinking about the center’s overall mission and purpose. What if the center was an incubator? What would that mean exactly? Or a sieve? Furthermore, these novel frameworks for understanding the work of the center encouraged participants to see their own work within the center in a new light. By thinking about the orientation of the center in terms previously unfamiliar to most of them, participants had, in turn, to reorient themselves. This reorientation disrupted the paradigms they had been used to thinking in, and this disruption offered opportunity for them to view their work from a different perspective. This encouraged the staff, who came from different professional backgrounds, to work together to formulate theories of change they thought best captured the work of the center.

This inclusive, iterative process encouraged the generation of new ideas about the center and, eventually, a theory of change that captured the essence of those ideas. The process helped the team not only to reach consensus on the statement’s underlying assumptions, as Reinholz and Andrews (2020, p. 2) noted, but also to understand that those assumptions were mutable and could change to meet the needs of those affected by them.

This was not by accident. Pretty (1995) described some less-desirable forms of participation, including manipulative participation, in which people are invited to the decision-making process but have no real power to influence it, as well as passive participation, in which decisions have already been made. Cognizant of the importance of creating a space for equitable participation, the center wanted to ensure the process by which they developed their theory of change embodied elements of successful participatory decision-making. This process offers a nice roadmap for large CTLs that would initiate a theory of change process that invites a large and professionally diverse staff to participate. This roadmap, moreover, could be used to inform the development of mission statements, value statements, visions statements, and other such statements of change and intention.

But what of smaller CTLs, or “centers of one”? The process outlined above can easily be adapted to fit the needs of smaller centers. A small CTL that seeks additional collaborators could reach out to the units they work with most closely to help formulate a theory of change. Indeed, a theory of change could occasion the cultivation of new connections across campus, thereby enhancing the influence a smaller CTL might have within the university. The initial stage of center-wide reflection, for example, could be replaced by a session that invites stakeholders from across the university to share reflections on the CTL’s metaphorical orientation within the university. A smaller group could then convene for discussion, with the center’s head drafting a unified theory of change. The final stage could again invite those stakeholders to share thoughts about the draft theory of change. This multi-unit process does introduce complexity, but we feel the additional feedback enriches the resulting theory of change.

We suggest that CTLs wanting to develop a theory of change according to participatory decision-making best practices would benefit from ensuring that the process:

remains simple enough for all to participate while remaining powerful enough to direct change,

contains adequate representation and inclusion in the decision-making phases of the process,

ensures all parties have the knowledge they need to participate in the process,

remains open enough to include contributions from different knowledge bases,

creates space for deliberation,

accommodates deliberation and individual contributions,

builds in accountability and feedback loops,

remains flexible enough to accommodate change and dissent, and

engages large and small groups through various draft-generating activities.

Although the center’s theory of change is still new, we have started to apply it in various aspects of our work and have imagined other implications as well. For instance, one staff member suggested that the theory of change might influence new programs and strategic initiatives, and we have started to use it as framing for these discussions in our faculty and graduate student programs group. Another colleague suggested applying the theory to assessment, prompting thinking about harmonizing it with the center’s evaluation matrix (Ellis et al., 2020) and other assessments.

The theory of change raises broader questions for our organization as well. If, according to our theory of change, our work rests on creating inclusive, supportive teaching and learning communities, what gaps are there in our programs? If we are to foster interdisciplinary and intergenerational relationships built on trust, what levers of credibility (Little & Green, 2022) can we employ to build trust? As the center’s work continues to build on our theory of change, we imagine that we will be able to open up other conversations to move forward our work in teaching and learning. We hope that the process described here will similarly open up generative conversations to help CTLs make explicit their theories of change. CTLs are increasingly engaged in change management processes, both intra- and inter-institutional (Grupp & Little, 2019; Kim & Maloney, 2020; Schroeder, 2011; Timmermans, 2014; Weston et al., 2017). Our theory of change is that by making our hypotheses about contextual transformation explicit through participative deliberation, we position CTLs to be effective change agents.

Biographies

Dana Hayward is the Assistant Director for Assessment and Evaluation at the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning at Brown University.

Christine Baumgarthuber is a Senior Learning Designer at the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning at Brown University.

Mary C. Wright is Associate Provost for Teaching and Learning, Executive Director of the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, and Professor (Research) in the Department of Sociology at Brown University.

Jennifer J. Kim is the Director of the Multilingual Learner (MLL) Certification Program at the Providence Public School District.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the editors and reviewers at To Improve the Academy for their helpful comments and suggestions.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

References

ActKnowledge and Aspen Institute Roundtable on Community Change. (2003). Guided example: Project Superwomen. https://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/Superwomen_Example.pdfhttps://www.theoryofchange.org/wp-content/uploads/toco_library/pdf/Superwomen_Example.pdf

Beach, A. L., Sorcinelli, M. D., Austin, A. E., & Rivard, J. K. (2016). Faculty development in the age of evidence: Current practices, future imperatives. Stylus Publishing.

Bell, K., & Reed, M. (2022). The tree of participation: A new model for inclusive decision-making. Community Development Journal, 57(4), 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsab018https://doi.org/10.1093/cdj/bsab018

Bolman, L. G., & Deal, T. E. (2008). Reframing organizations: Artistry, choice, and leadership (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Connolly, M. R., & Seymour, E. (2015). Why theories of change matter (Working Paper No. 2015–2). Wisconsin Center for Education Research, University of Wisconsin. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED577054.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED577054.pdf

Cruz, L., Parker, M. A., Smentkowski, B., & Smitherman, M. (2020). Taking flight: Making your center for teaching and learning soar. Stylus Publishing.

Ellis, D. E., Brown, V. M., & Tse, C. T. (2020). Comprehensive assessment for teaching and learning centres: A field-tested planning model. International Journal for Academic Development, 25(4), 337–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1786694https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2020.1786694

Felten, P., Kalish, A., Pingree, A., & Plank, K. M. (2007). Toward a scholarship of teaching and learning in educational development. To Improve the Academy, 25. https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0025.010https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0025.010

Grupp, L. L., & Little, D. (2019). Finding a fulcrum: Positioning ourselves to leverage change. To Improve the Academy, 38(1). https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0038.103https://doi.org/10.3998/tia.17063888.0038.103

Kelley, B., Cruz, L., & Fire, N. (2017). Moving toward the center: The integration of educational development in an era of historic change in higher education. To Improve the Academy, 36(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20052https://doi.org/10.1002/tia2.20052

Kezar, A. (2018). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Kezar, A., Gehrke, S., & Elrod, S. (2015). Implicit theories of change as a barrier to change on college campuses: An examination of STEM reform. The Review of Higher Education, 38(4), 479–506.

Kim, J., & Maloney, E. (2020). Learning innovation and the future of higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Little, D., & Green, D. A. (2012). Betwixt and between: Academic developers in the margins. International Journal for Academic Development, 17(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2012.700895https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2012.700895

Little, D., & Green, D. A. (2022). Credibility in educational development: Trustworthiness, expertise, and identification. Higher Education Research & Development, 41(3), 804–819. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1871325https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1871325

Miller-Young, J., Marin, L. F., Poth, C., Vargas-Madriz, L. F., & Xiao, J. (2021). The development and psychometric properties of an educational development impact questionnaire. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101058. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101058https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101058

Özdem, G. (2011). An analysis of the mission and vision statements on the strategic plans of higher education institutions. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 11(4), 1887–1894.

POD Network. (2018). Defining what matters: Guidelines for comprehensive center for teaching and learning (CTL) evaluation. POD Network. https://podnetwork.org/content/uploads/POD_DWM_R3-singlepage-v2.pdfhttps://podnetwork.org/content/uploads/POD_DWM_R3-singlepage-v2.pdf

Pretty, J. N. (1995). Participatory learning for sustainable agriculture. World Development, 23(8), 1247–1263. https://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00046-Fhttps://doi.org/10.1016/0305-750X(95)00046-F

Reinholz, D. L., & Andrews, T. C. (2020). Change theory and theory of change: What’s the difference anyway? International Journal of STEM Education, 7, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-0202-3https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-0202-3

Reinholz, D. L., Pawlak, A., Ngai, C., & Pilgrim, M. (2020). Departmental action teams: Empowering students as change agents in academic departments. International Journal for Students as Partners, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v4i1.3869https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v4i1.3869

Schroeder, C. M. (2011). Aligning and revising center mission statements. In C. M. Schroeder & Associates, Coming in from the margins: Faculty development’s emerging organizational development role in institutional change (pp. 235–259). Stylus Publishing.

Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). About. Retrieved March 11, 2024, from https://www.brown.edu/sheridan/abouthttps://www.brown.edu/sheridan/about

Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning. (2022, April). Sheridan Center evaluation matrix. https://www.brown.edu/sheridan/sites/sheridan/files/docs/Sheridan%20Evaluation%20Matrix%202022.pdfhttps://www.brown.edu/sheridan/sites/sheridan/files/docs/Sheridan%20Evaluation%20Matrix%202022.pdf

Stevens, M. L., Armstrong, E. A., & Arum, R. (2008). Sieve, incubator, temple, hub: Empirical and theoretical advances in the sociology of higher education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34, 127–151. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134737https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134737

Takayama, K., Kaplan, M., & Cook-Sather, A. (2017). Advancing diversity and inclusion through strategic multilevel leadership. Liberal Education, 103(3–4), 22–29.

Timmermans, J. A. (2014). Identifying threshold concepts in the careers of educational developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 19(4), 305–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2014.895731https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2014.895731

Weston, C., Ferris, J., & Finkelstein, A. (2017). Leading change: An organizational development role for educational developers. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 29(2), 270–280.

Wright, M. C. (2023). Centers for teaching and learning: The new landscape in higher education. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Appendix Summary of themes from small-group discussion

Group 1: Hub and Temple

Promoting and highlighting the value of teaching

Invitational, engaging, inclusive

Evidence-based

Collaboration and relationships

Interdisciplinary

Cross-community

Intergenerational

Non-hierarchical

Trusting

Innovation and exploration

Relationship-building

Group 2: Incubator and Sieve

[Inclusive, best, evidence-based] practices

Experts, exemplars

Faculty and learners

Trust and self-efficacy

Providing time, space, opportunities, resources, tools

Community, partnership, collaboration

Experiment, problem-solve

Create, actualize, practice

Faculty feeling supported in their experiments

Bringing people together

Engaged learning, growth as a learner

Knowledge creation

Practical principles