Indirect or direct exclusion of students by race, ethnicity, gender, religion, sexual orientation, disability status, socioeconomic class, first-generation status, and other social identities or attributes has a long-standing history in higher education, which is problematic for student access to and persistence in higher education. Practically, this can be seen by high DFW (D or F grade or withdraw) rates of students from groups historically marginalized (Roberts et al., 2018), lack of diversity in curricula (Booker & Campbell-Whatley, 2015; Dee & Penner, 2016; Sumner et al., 2017), students not having appropriate accommodations (Lyman et al., 2016), students unable to purchase required course materials because of limited financial means (Jung et al., 2017), a necessity for students to navigate institutions where social capital plays a large role in achievement (Bancroft, 2013; McPherson, 2014), and a lack of diverse role models and mentors (Li & Koedel, 2017; Taylor et al., 2010).

Inclusive teaching involves fostering equitable, welcoming environments for diverse learners, which individual instructors could utilize to combat inequity. In this regard, inclusive teachers are responsive to individual differences between their students and modify instruction accordingly to help their learners attain academic goals (Dewsbury & Brame, 2019). Some examples of inclusive teaching practices include assessing students’ prior knowledge and planning instruction to account for differences, implementing teaching strategies that encourage equitable participation from all learners, learning and using student names, utilizing students’ pronouns, developing accessible digital course materials, considering avenues for making course materials more affordable, and revising courses to include diverse authors and examples.

Understanding which factors influence whether instructors implement inclusive teaching approaches is critical given shifting student demographics on college and university campuses and the necessity to be responsive to such change. Generation Z, learners born between 1995 and 2012, are in today’s classrooms. Gen Z learners exhibit the highest racial diversity of any previous generation with 48% being non-White (Cilluffo & Cohn, 2019; Twenge, 2017). In 2015 to 2016, of the 20 million students enrolled in postsecondary education, 47% were non-White and 31% at the poverty level (Fry & Cilluffo, 2019). In 2011 to 2012, approximately one-third of the college population was estimated to be first-generation learners whose parents did not attend college (Skomsvold, 2014). In prior research, low-income, first-generation learners were reported to make up approximately 24% of the postsecondary student population and to be four times as likely to leave college after their first year (Engle & Tinto, 2008). International students have been reported to make up roughly 5% of learners in higher education, a five-fold increase from 60 years prior (Institute of International Education, 2017). A summary report of diversity and inclusion data and promising practices in higher education is available through the United States Department of Education (2016).

Such demographic changes on college campuses necessitate instructor adoption of equitable, welcoming teaching practices to support an increasingly diverse student population, who themselves are more tolerant of diversity and invested in social justice and change (Parker & Igielnik, 2020; Seemiller & Grace, 2016; Twenge, 2017).

Advancing Inclusive Teaching

In general, educational resources and development opportunities have the potential to advance instructor awareness of the exclusion of students with diverse social identities, help faculty recognize their own biases, and support instructor adoption of inclusive teaching approaches (Dewsbury & Brame, 2019; Friedrich et al., 2017; Hockings, 2010; Killpack & Melón, 2016; Penner, 2018; Tanner, 2013). There are a number of frameworks that support the inclusive teaching efforts of instructors. The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST, 2020) developed resources on universal design for learning (UDL) aimed to make learning accessible for all students. The UDL movement continues to spread in higher education as practices such as taking a “plus-one” approach, or adding one more element to a course to reduce barriers to learning, are recommended (Tobin & Behling, 2018). Culturally responsive and relevant pedagogies emphasize the importance of acknowledging and countering the history of systemic oppression in education experienced by students from marginalized groups (Gay, 2018; Ladson-Billings, 2014; Paris, 2012). Elements include setting up course environments in which all students are capable of succeeding and designing learning experiences that intentionally take into account the cultural assets that students bring to a course. Furthermore, the development and enactment of department- and institution-wide strategic plans around inclusive teaching involving multiple campus partners can accelerate efforts to foster equitable environments for diverse learners at colleges and universities (Kezar, 2013).

A variety of organizations also support inclusive teaching within higher education. In 2018, the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) released the statement “Diversity, Equity, and Inclusive Excellence” demonstrating commitment to inclusion in higher education (AAC&U, 2013). The AAC&U (2015) also has a campus guide for institutions to engage in a self-study to advance inclusive teaching efforts. The National Center for College Students with Disabilities (NCCSD, 2020) produced research briefs to promote awareness of access concerns faced by students with disabilities and provide recommendations. The Howard Hughes Medical Institute (n.d.) initiated the Inclusive Excellence initiative to provide grant funding to institutions furthering their inclusive teaching efforts within STEM fields. The Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning (2020) offers professional development support for future faculty in science on inclusive teaching and received funding from the National Science Foundation to carry out efforts. This list provides examples of initiatives designed to advance inclusive teaching but is not exhaustive.

At the institutional level, centers for teaching and learning (CTLs) continue to provide professional development to instructors with regard to inclusive teaching. However, unfortunately, professional development addressing inclusive teaching may only be experienced by a small number of instructors at a given institution, limiting institutional change efforts. Some institutions are confronting this challenge by integrating inclusive teaching into institutional rewards systems for promotion and tenure review (e.g., University of Oregon, 2019) or incorporating inclusive teaching into diversity plans and utilizing the services of CTLs to further efforts. Yet despite the national discourse occurring around inclusive pedagogy, there is limited empirical evidence governing what predicts instructor implementation of inclusive teaching approaches.

Study Objectives

The aims of this national survey study were to take a broad view of inclusive teaching to (a) identify factors that predicted whether instructors report utilizing inclusive teaching approaches (regression analyses); (b) categorize the challenges instructors encountered either individually, departmentally, or institutionally with implementing such approaches (thematic analysis); and (c) provide recommendations informed by these factors as well as instructor perceptions of how institutions can advance change initiatives and be more inclusive of their learners. This work foregrounds institutional change around inclusive teaching. When campus partners such as instructors, department chairs, educational developers, and administrative staff develop an awareness of the key predictors, barriers, and initiatives to drive change toward equitable and inclusive teaching, they can carry out initiatives that advance institutional goals toward inclusive excellence.

The specific research questions guiding this investigation were the following:

What predicts whether instructors from diverse disciplines report implementing inclusive teaching approaches?

What are their reported barriers to implementation?

What are instructors’ views on how academia can lead change and advance inclusive pedagogy efforts?

Materials and Methods

Research Design Overview

This was a descriptive, mixed methods investigation involving the distribution of a survey and the subsequent analysis of quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative numerical data were obtained through Likert scale survey items and qualitative data through respondents’ narrative comments (see Appendix A). This design was utilized to identify the factors that predict the use of inclusive teaching practices and to identify instructors’ perspectives of both the barriers to implementation and promising change initiatives that are occurring. This study involved thematic analysis and not content analysis. These research methods have overlap but also differences. As described by Neuendorf (2019), thematic and content analyses each involve coding data and identifying variables or constructs. Content analysis comes from a positivist approach to use quantitative techniques and thematic analysis from a more constructivist approach. In thematic analysis, the instructors’ comments are considered the data, and the codes develop as themes emerge. Content analysis assumes that the comments are the phenomena to be studied. In content analysis, the coded variables are typically summarized in a quantitative manner (Neuendorf, 2019). For thematic analysis, as noted by Neuendorf, “the frequency of occurrence of specific codes or themes is usually not the main goal of the analysis” (p. 212).

Data Sources

The Inclusive Teaching Questionnaire was designed for this study and consisted of 18 Likert scale items, eight open-ended questions, and an array of demographic questions. The full instrument is available in Appendix A. Responses to Likert scale items, which measured agreement on a 6-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree) were analyzed in SPSS. To address different aspects of inclusive teaching, the Likert scale items were presented in five sections: knowledge of inclusive teaching (four items), utilization of inclusive teaching practices (four items), departmental support of inclusive teaching (three items), institutional support for inclusive teaching (three items), and opinions about the progress being made at various levels in regard to inclusive pedagogy (four items).

Validity and Reliability

To provide content validity evidence, the items on the questionnaire were generated by content experts in faculty development, educational psychology, and inclusive teaching practitioners (AERA, APA, and NCME, 2014). The five sections of the survey each had the following reliability measures: knowledge of inclusive teaching (α = 0.94), utilization of inclusive teaching practices (α = 0.84), departmental support of inclusive teaching (α = 0.83), institutional support for inclusive teaching (α = 0.82), and opinions about the progress being made at various levels in regard to inclusive pedagogy (α = 0.80).

Participant Recruitment

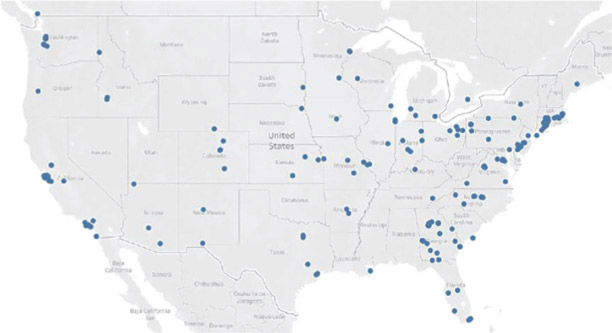

The survey questions were distributed anonymously using Qualtrics. Invitations to participate were directly sent to over 30 higher education institutions (generally to their CTLs for subsequent distribution to their faculty) that are located in various geographical regions of the United States and represent diverse institutional types, including private and public, large and small, universities, state colleges, liberal arts colleges, historically Black universities and colleges, seminaries, and community colleges. To further the reach of the survey, invitations to participate were also sent through consortiums and listservs (e.g., Professional and Organizational Development [POD] Network, Consortium for Faculty Diversity [CFD], Council on Undergraduate Research [CUR], New England Faculty Development Consortium [NEFDC], etc.) and posted on social media platforms (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn). The responses were collected from January 12, 2019, to February 26, 2019. The median response time was 14 minutes, 55 seconds. Respondents did not receive compensation for participating in the study, and information related to the purpose, procedures, institutional review board approval, benefits, risks, and other relevant information was provided prior to participation. The survey was closed when the responses slowed down to nearly zero.

Study Participants

A total of 566 participants started the survey. Of that number, 306 participants reached the end of the survey and submitted responses. In total, 214 participants responded to all of the questions that were included in the quantitative analysis portion of this study. Given that the survey distribution included networks and social media, response rates could not be calculated. The sample included 180 females (84.11%), 174 individuals that identified as White and non-Hispanic (81.31%), 118 tenured or tenure-track faculty (55.14%), 175 full-time faculty (81.78%), 97 faculty who worked at a doctoral granting institution (45.33%), 162 faculty who had participated in professional development activities that focused on inclusive teaching (75.70%), and 132 faculty from STEM fields (61.67%). Faculty from 44 academic disciplines responded to the survey. Disciplines were classified as STEM or non-STEM fields based on the U.S. Department of Homeland Security, Immigration and Custom Enforcement criteria (Department of Homeland Security, 2016). These demographic breakdowns, geographic location of respondents, and the mean number of years of teaching experience (14.36 years; SD = 8.94) can be found in Appendix B.

Analysis and Results

The following section includes an overview of analyses conducted with data gathered from each of the Likert scales. Appendix C and the tables provide more detailed descriptive statistics and results with data from all groups.

Knowledge and Utilization of Inclusive Teaching Approaches—Descriptive Statistics

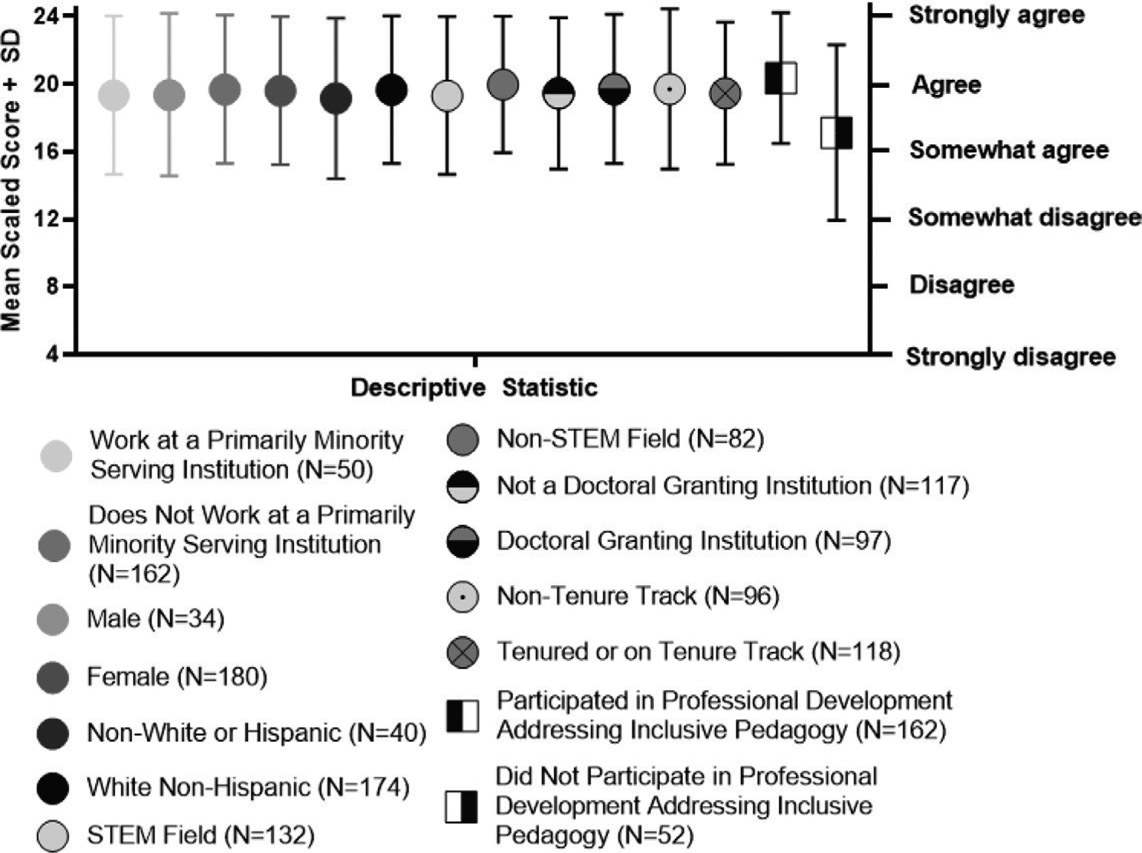

The mean sum scale score (i.e., we added scores for all items in the scale, divided by the number of items, then calculated the mean across all participants) across questions measuring the respondents’ perceived knowledge of inclusive teaching and inclusive teaching practices was 19.56 (SD = 4.44, n = 214; Figure C1). This mean fell between the expected values representing somewhat agree and agree, at 16.00 and 20.00, respectively. The highest mean (20.35, SD = 3.87, n = 162) was found for those who had participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy, and the lowest mean (17.12, SD = 5.19, n = 52) for individuals stating that they did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy.

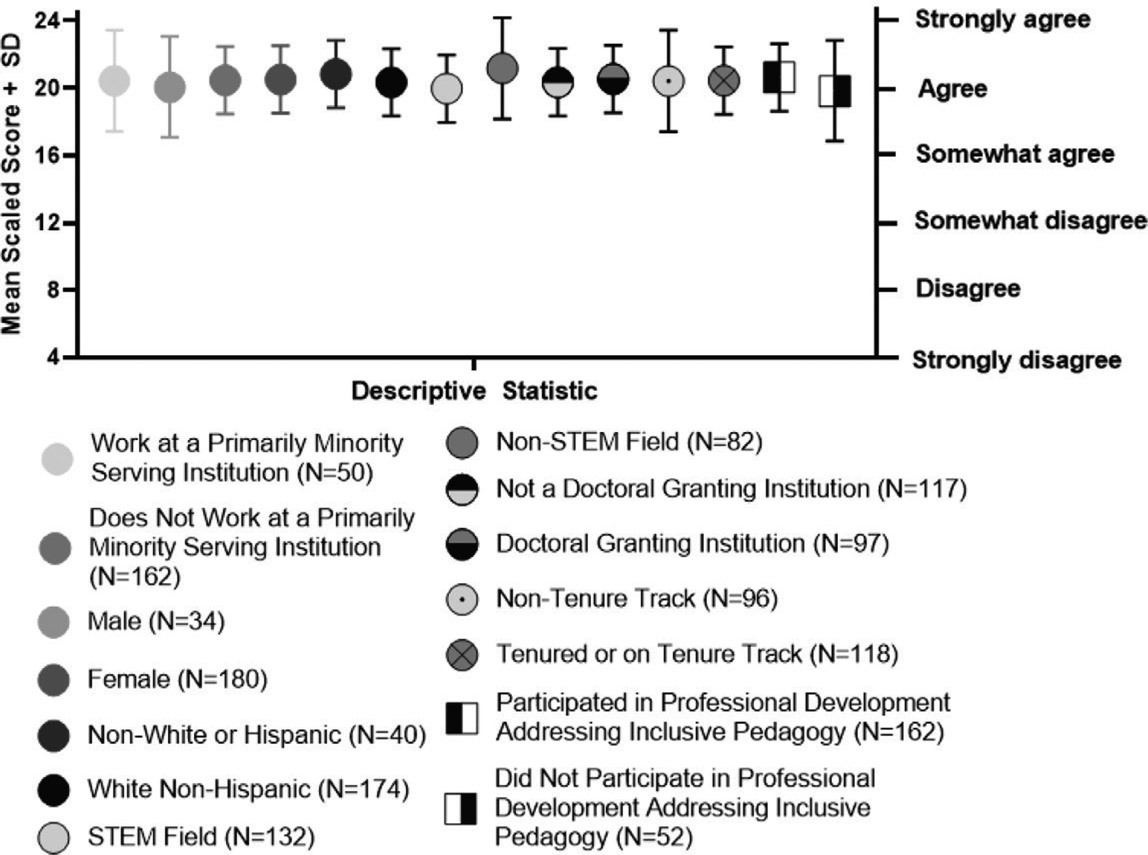

The mean sum scale score across questions measuring the utilization of inclusive pedagogies was 20.43 (SD = 2.89, n = 214; Figure C2). This mean fell between the expected values representing agree and strongly agree, at 20.00 and 24.00, respectively. The lowest mean, 19.83 (SD = 3.00, n = 52), was found for the group of respondents indicating that they did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy, although this value was still in the range of somewhat agree to agree responses. The highest mean, 21.18 (SD = 3.12, n = 82), was present in faculty respondents from non-STEM disciplines.

Department and Institutional Support of Inclusive Teaching—Descriptive Statistics

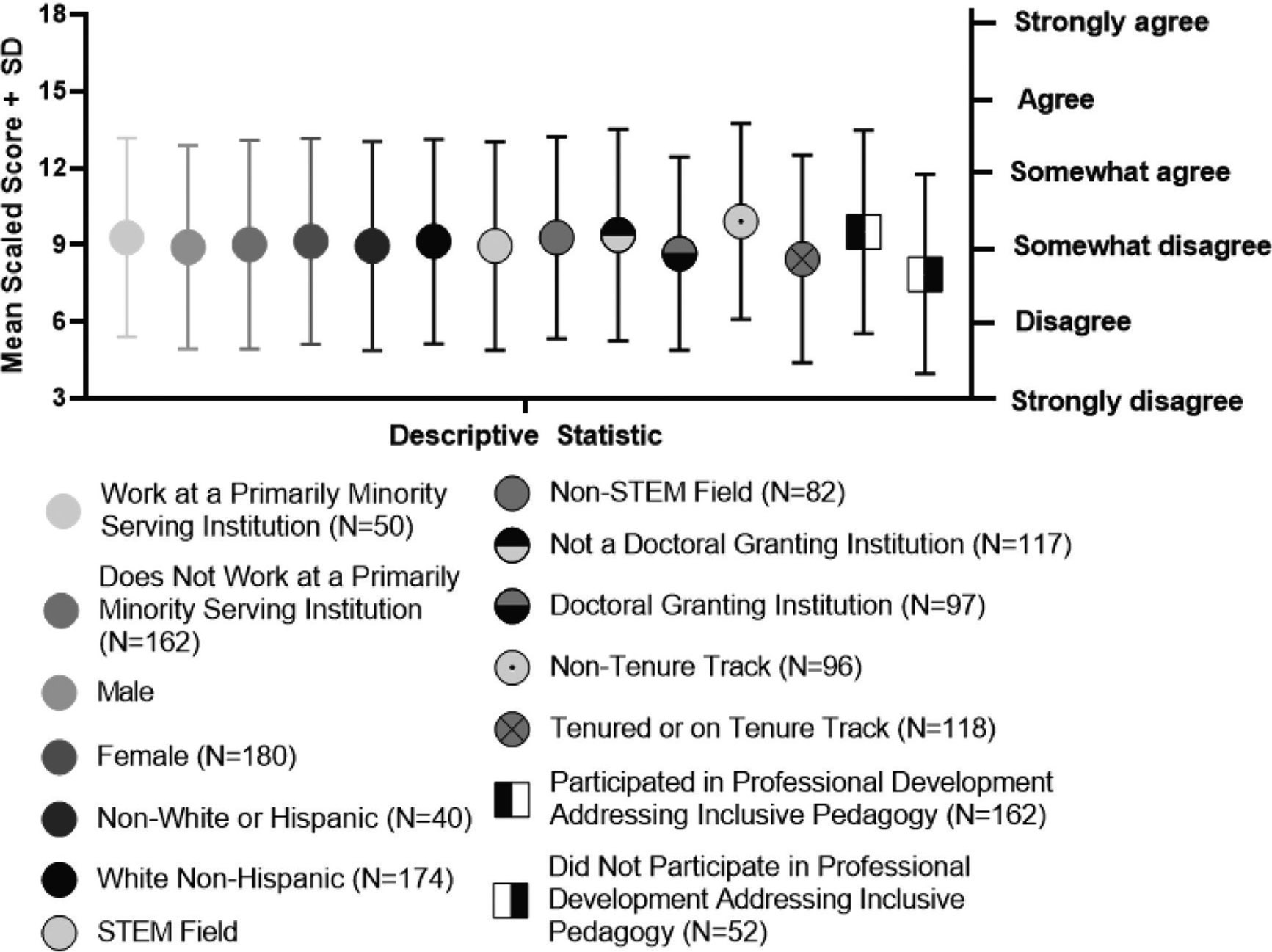

The mean of the summed scores of all respondents on questions measuring departmental support for inclusive teaching was 9.10 (SD = 4.00, n = 214; Figure C3). This score fell between the expected values for somewhat disagree and somewhat agree, 9.00 and 12.00, respectively, but closer to somewhat disagree. The lowest mean was found in respondents who indicated they did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy, at 7.85 (SD = 3.89, n = 52), which fell between the expected value of 6.00 for disagree and 9.00 for somewhat disagree responses. Additionally, it is noteworthy that faculty who identified as being either tenured or on the tenure track had a mean of 8.44 (SD = 4.05, n =118), whereas the highest mean in all groups, 9.91 (SD = 3.82, n = 96), was found in those identifying as non-tenure track, though this value is still below the mean expectation for somewhat agree responses.

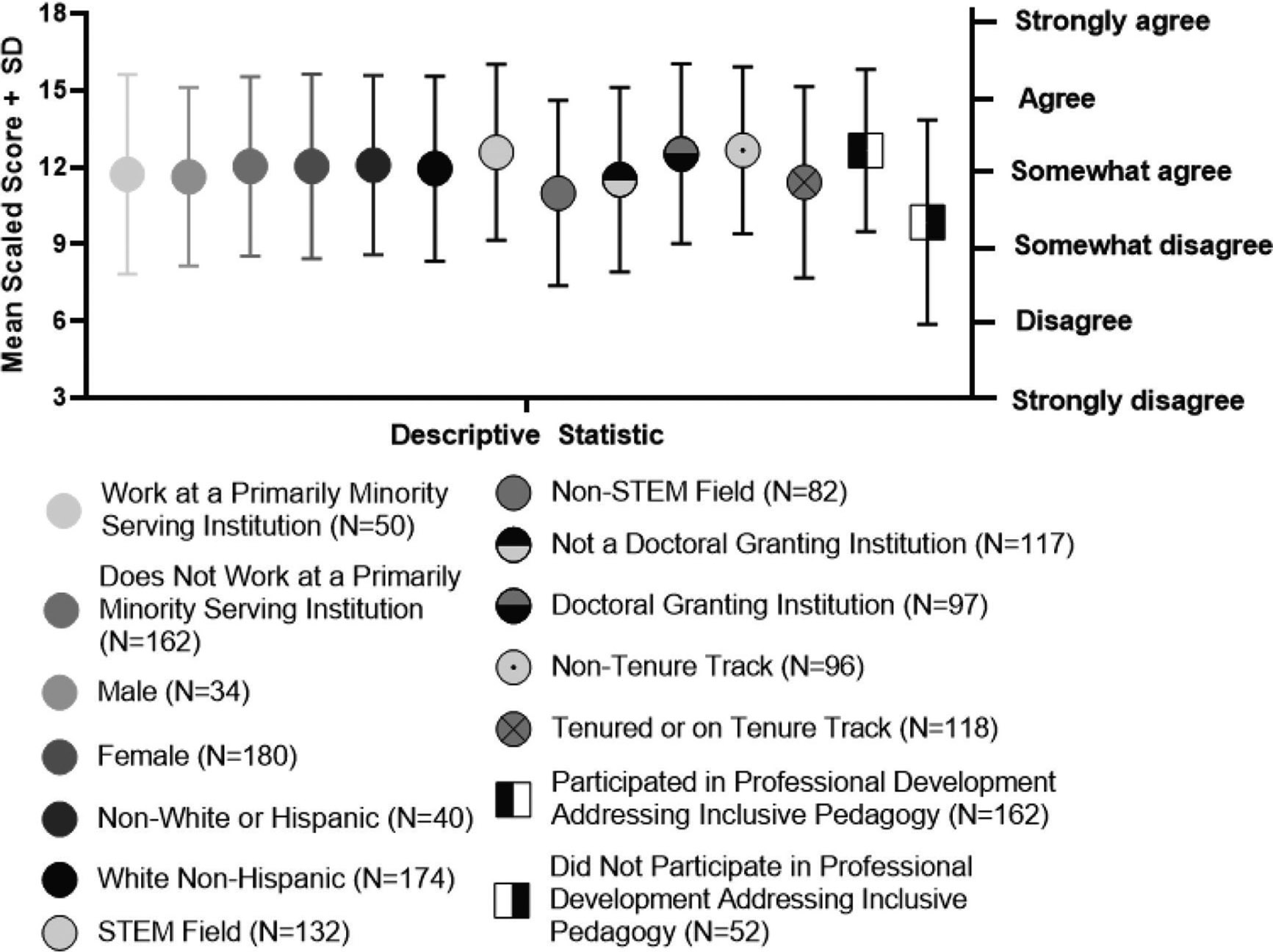

The overall mean for the summed questions addressing institutional support for inclusive teaching was higher than that seen for departmental support, at 11.97 (SD = 3.58, n = 214), almost precisely equaling the expected value for somewhat agree responses of 12.00 (Figure C4). The highest mean value again was identified in the non-tenure track respondents, at 12.66 (SD = 3.26, n = 96). The lowest mean was found from respondents indicating they did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy, at 9.85 (SD = 3.99, n = 52), closest to the somewhat disagree expected value of 9.00.

Predicting Utilization of Inclusive Teaching Practices

A simultaneous multiple regression equation was used to examine variables that predicted utilization of inclusive teaching practices. The assumptions of linearity, independence, normality, and homoscedasticity were tested and met. The dependent variable was the sum scale score of the questions measuring utilization of inclusive teaching practices. Independent variables included the sum scale score of the questions measuring knowledge of inclusive teaching; the sum scale score of the questions measuring departmental support of inclusive teaching; the sum scale score of the questions measuring institutional support for inclusive teaching; years of teaching experience; participation in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy (no = 0, yes = 1); gender (male = 0, female = 1); ethnic or racial minority (non-White or Hispanic = 0, White and non-Hispanic = 1); tenure track status (non-tenure-track = 0; tenured or tenure-track = 1); discipline (non-STEM = 0, STEM = 1); and teaching at a doctoral granting institution (no = 0, yes = 1).

The results of the multiple regression analysis measuring predictors of utilization of inclusive teaching approaches indicated that the 10 predictors explained 29.10% of the variance (R2 = 0.29, adjusted R2 = 0.26, F(10, 203) = 8.33, p < .01). The results indicated that discipline (i.e., STEM versus non-STEM; β = −1.17, t(202) = −3.21; p = .002) and the knowledge score (β = 0.30, t(202) = 7.11; p < .001) significantly predicted the utilization score (Table 1). Using this model, the average STEM faculty had an average utilization score 1.17 points less than non-STEM faculty, and faculty with higher knowledge scores had higher utilization scores when holding all of the other variables constant.

Regression Coefficients for Equation Predicting the Utilization of Inclusive Teaching Practices

| Unstandardized coefficients | Standardized coefficients | t | Sig. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | S.E. | β | |||

| (Constant) | 13.34 | 1.47 | 9.05 | 0.00 | |

| Gender | 0.39 | 0.48 | 0.05 | 0.81 | 0.42 |

| White non-Hispanic | −0.68 | 0.44 | −0.09 | −1.54 | 0.13 |

| STEM* | −1.17 | 0.37 | −0.20 | −3.21 | 0.00 |

| Doctoral granting institution | 0.06 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 0.16 | 0.87 |

| Tenured or tenure track | 0.11 | 0.37 | 0.02 | 0.31 | 0.76 |

| For how many years have you been teaching? | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.53 | 0.60 |

| Knowledge* | 0.30 | 0.04 | 0.46 | 7.11 | 0.00 |

| Institutional support | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.13 | 1.52 | 0.13 |

| Departmental support | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.17 | 0.86 |

| Participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy | 0.51 | 0.44 | 0.08 | 1.16 | 0.25 |

* Statistically significant

Perceptions of Progress in Inclusive Teaching

The Inclusive Teaching Questionnaire asked respondents about their perceptions of the level of progress being made on inclusive teaching efforts at four distinct levels: individual, departmental, institutional, and higher education overall. Descriptive statistics and a logistic regression equation are presented for each level (individual, departmental, institutional, and across higher education). The regression equations examined how individuals with different demographics perceived the progress that is made at each level. The dependent variable for each equation was a single item rating agreement for a specific level. Categories for agreement were collapsed into two categories (disagree = 0, agree = 1) because the sample size in each of the original six categories of agreement was too small when cross-tabbing across multiple demographic variables. The independent variables included participating in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy (no = 0, yes = 1); gender (male = 0, female = 1); race/ethnicity (non-White or Hispanic = 0, White and non-Hispanic = 1); tenure track status (non-tenure track = 0; tenured or tenure-track = 1); discipline (non-STEM = 0, STEM = 1); and teaching at a doctoral granting institution (no = 0, yes = 1).

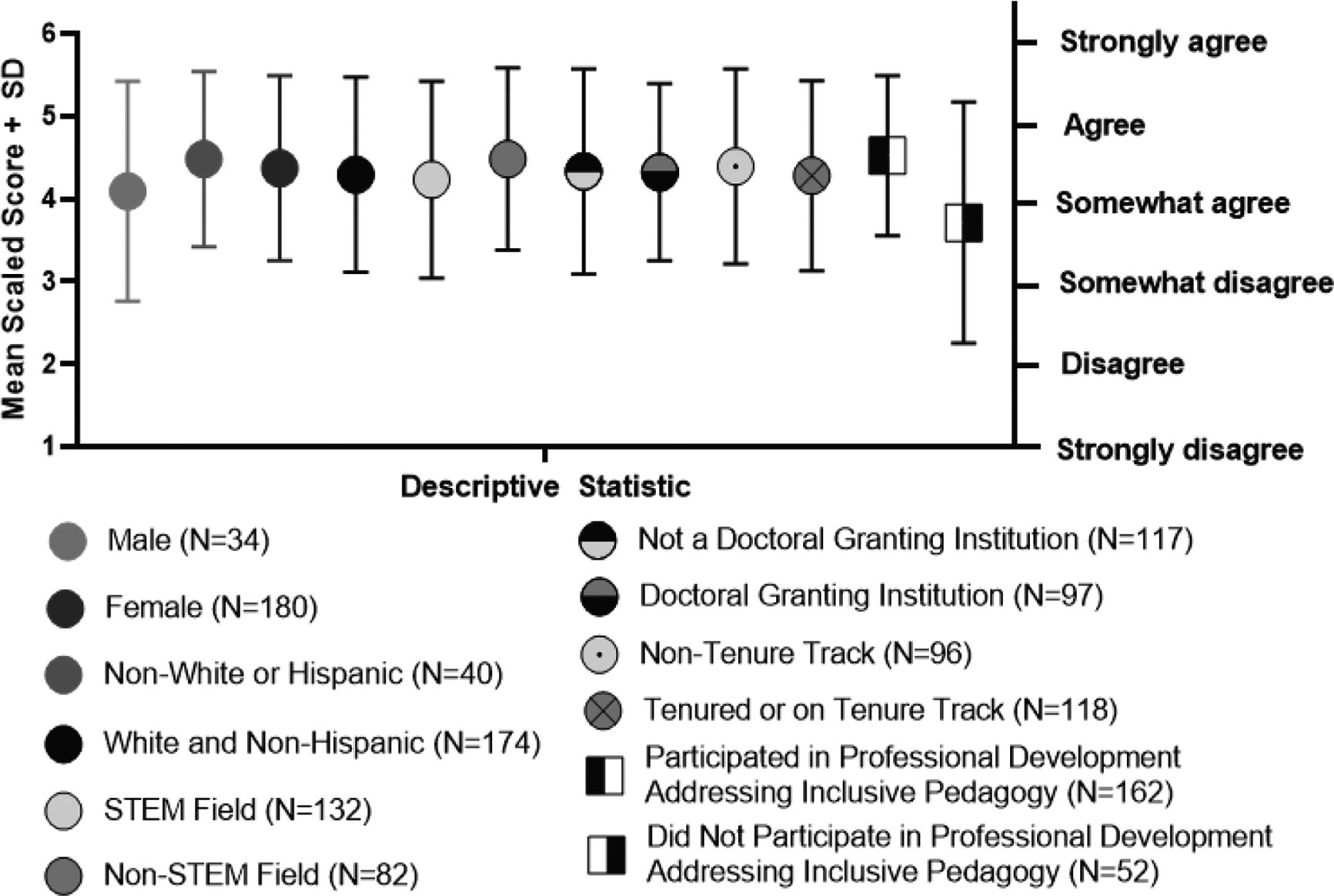

Descriptive statistics for the item “I am making enough progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy” are broken down by demographic characteristics in Figure C5. The overall mean of all respondents was 4.33 (SD = 1.16, n = 214), a value that fell between somewhat agree (4.00) and agree (5.00). The demographic with the highest mean was those who had participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy at 4.52 (SD = 0.97, n =162), and the lowest mean was in the group who stated they did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy at 3.71 (SD = 1.46, n = 52). This represented the only group falling below the somewhat agree threshold. Results from the logistical regression equation related to individual progress are presented in Table 2. Variance inflation factor and the Box-Tidwell test were examined to ensure that the assumptions of multicollinearity and the linearity of independent variables with log odds were met, respectively. The logistic regression model was statistically significant, χ2(7) = 28.35, p < .001. The model explained 20.10% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in agreement and correctly classified 81.3% of cases. Using this model, individuals who participated in professional development activities were 6.25 times more likely to agree with the statement that they were making enough progress with inclusive pedagogy.

Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting the Following Item: I Am Making Enough Progress With Regard to Inclusive Pedagogy

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Gender | 0.17 | 0.49 | 0.11 | 1.00 | 0.74 | 1.18 | 0.45 | 3.11 |

| White non-Hispanic | −0.52 | 0.52 | 0.98 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 0.59 | 0.22 | 1.66 |

| Discipline STEM | −0.55 | 0.41 | 1.79 | 1.00 | 0.18 | 0.58 | 0.26 | 1.29 |

| Doctoral | −0.31 | 0.40 | 0.60 | 1.00 | 0.44 | 0.74 | 0.34 | 1.60 |

| Tenured or tenure track | −0.08 | 0.40 | 0.04 | 1.00 | 0.83 | 0.92 | 0.42 | 2.02 |

| For how many years have you been teaching? | 0.04 | 0.02 | 2.60 | 1.00 | 0.11 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 1.08 |

| Have you participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy?* | 1.83 | 0.40 | 21.28 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 6.25 | 2.87 | 13.60 |

| Constant | 0.63 | 0.75 | .70 | 1.00 | 0.40 | 1.87 | ||

* Statistically significant

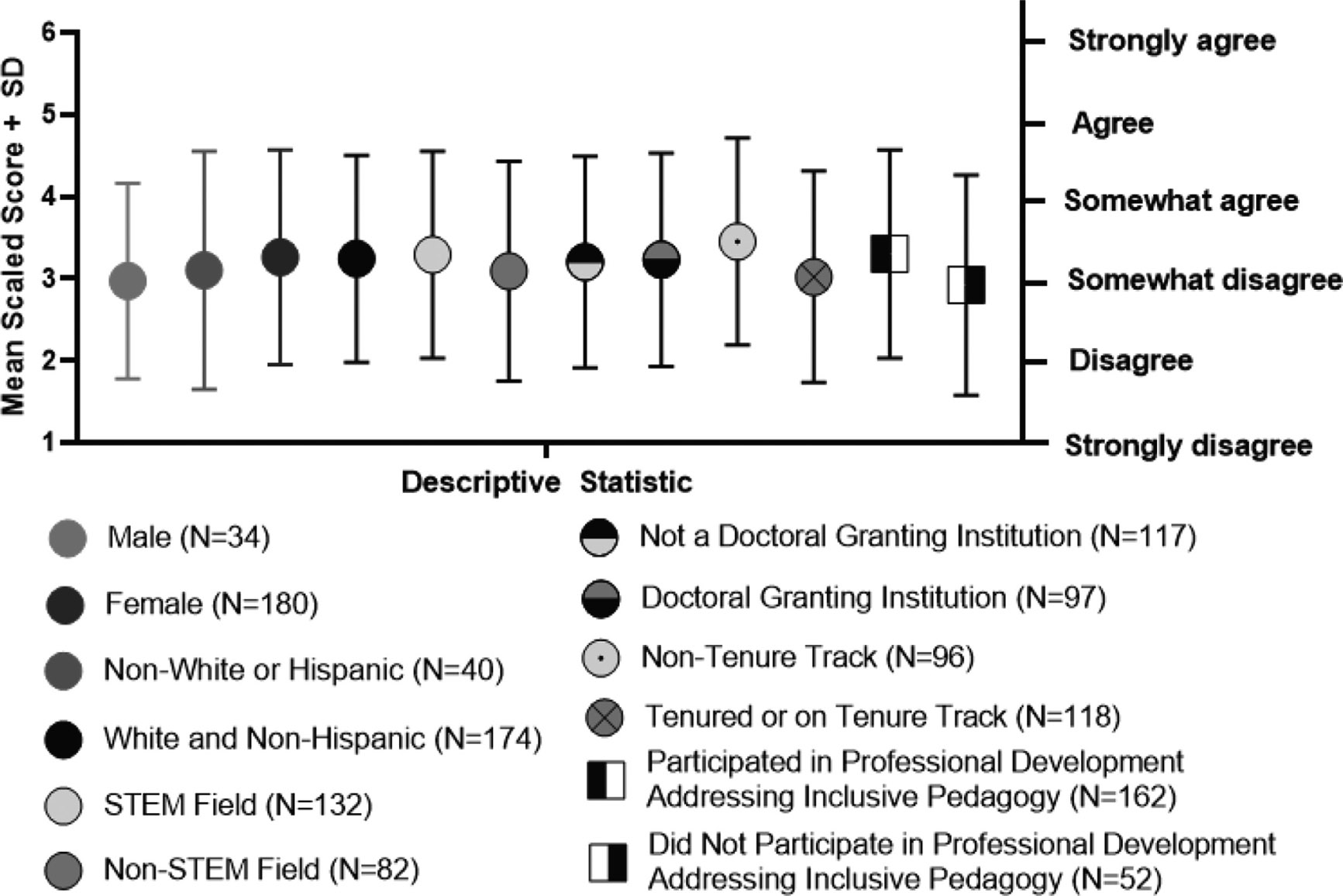

Descriptive statistics for the item “My department is making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy” are broken down by demographic characteristics in Figure C6. The overall mean of all respondents was 3.21 (SD = 1.29, n = 214), closest to the value for somewhat disagree (3.00). The demographic with the lowest mean (2.92, SD = 1.34, n = 52) was those who did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy, with the next lowest mean from males (2.97, SD = 1.19, n = 34). The highest mean was found in the non-tenure track instructors, at 3.45 (SD = 1.26, n = 96), though this value still fell below that of somewhat agree (4.00). The logistic regression model was not statistically significant, χ2(7) = 8.13, p = .32. The model explained 5.00% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in agreement and correctly classified 53.30% of cases (Table 3). Using this model, non-tenure track faculty were 0.52 times more likely than those that identified as tenured or on the tenure track to agree with the statement that their department is making sufficient progress with inclusive pedagogy.

Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting the Following Item: My Department Is Making Sufficient Progress With Regard to Inclusive Pedagogy

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Gender | 0.49 | 0.40 | 1.49 | 1 | .22 | 1.63 | 0.74 | 3.59 |

| White non-Hispanic | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 1 | .91 | 1.04 | 0.51 | 2.11 |

| Discipline STEM | 0.25 | 0.29 | 0.72 | 1 | .39 | 1.28 | 0.73 | 2.25 |

| Doctoral | −0.33 | 0.29 | 1.22 | 1 | .27 | 0.72 | 0.40 | 1.29 |

| Tenure or tenure track | −0.65 | 0.29 | 4.80 | 1 | .03 | 0.52 | 0.29 | 0.93 |

| For how many years have you been teaching? | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.05 | 1 | .83 | 1.00 | 0.97 | 1.04 |

| Have you participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy? | 0.27 | 0.34 | 0.65 | 1 | .42 | 1.31 | 0.68 | 2.53 |

| Constant | −0.48 | 0.59 | 0.65 | 1.00 | 0.42 | 0.62 | ||

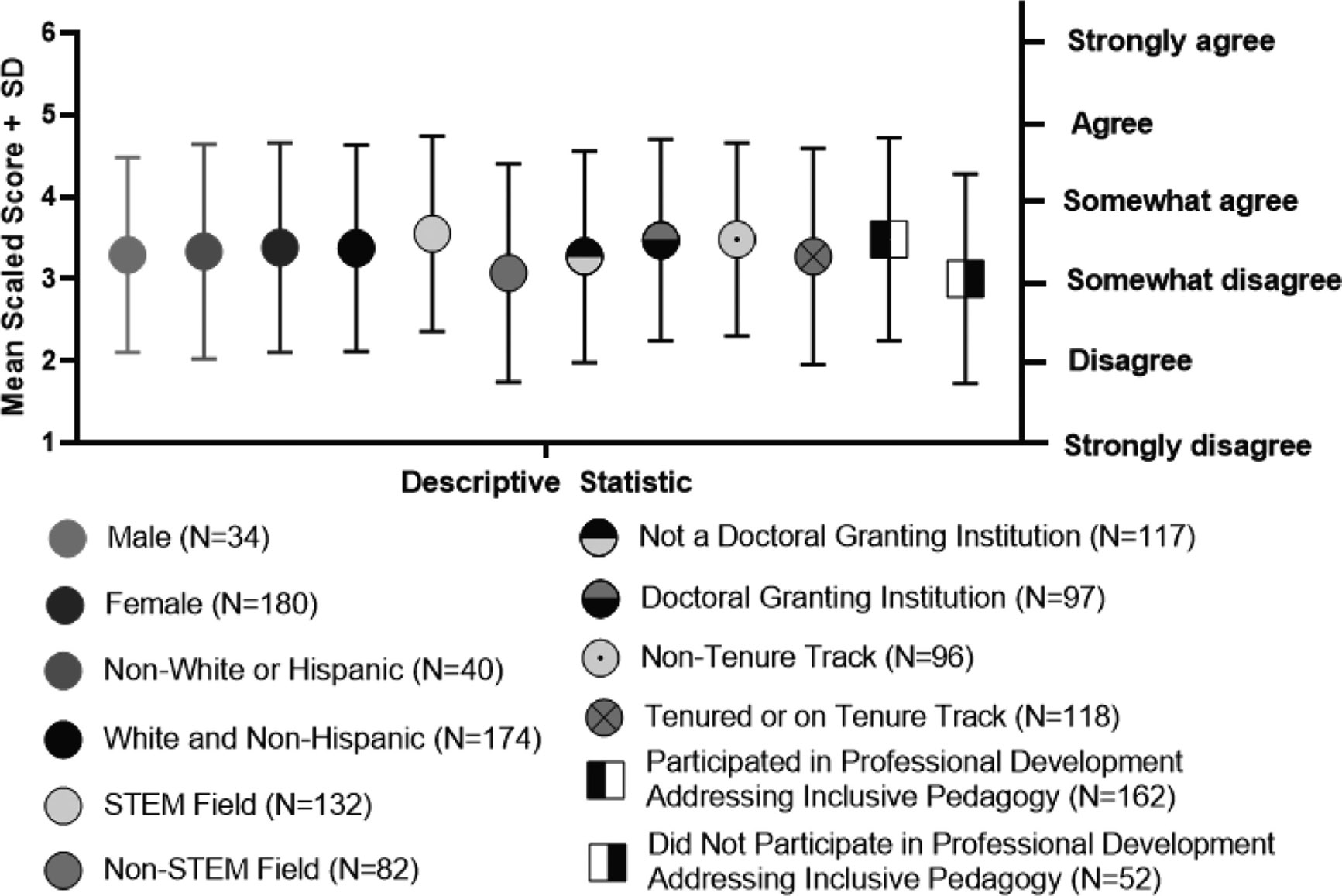

Descriptive statistics for the item “My institution is making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy” are broken down by demographic characteristics in Figure C7. The overall mean of all respondents was 3.36 (SD = 1.26, n = 214), closest to the value for somewhat disagree (3.00). The demographic with the lowest mean was those in non-STEM fields (3.07, SD = 1.33, n = 82), while the demographic with the highest mean was those in STEM fields (3.55, SD = 1.19, n = 132). All demographic groups responding to this question had means that were between somewhat disagree (3.00) and somewhat agree (4.00) responses. The logistic regression model was not statistically significant, χ2(7) = 4.66, p = .74. The model explained 2.70% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in agreement and correctly classified 53.70% of cases (Table 4).

Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting the Following Item: My Institution Is Making Sufficient Progress With Regard to Inclusive Pedagogy

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Gender | 0.39 | 0.39 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 0.32 | 1.48 | 0.69 | 3.19 |

| White non-Hispanic | 0.04 | 0.36 | 0.01 | 1.00 | 0.92 | 1.04 | 0.51 | 2.09 |

| Discipline STEM | 0.35 | 0.29 | 1.45 | 1.00 | 0.23 | 1.41 | 0.81 | 2.48 |

| Doctoral | 0.10 | 0.29 | 0.12 | 1.00 | 0.73 | 1.11 | 0.63 | 1.961 |

| Tenure or tenure track | 0.09 | 0.29 | 0.10 | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.09 | 0.62 | 1.95 |

| For how many years have you been teaching? | −0.01 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 1.00 | 0.70 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 1.03 |

| Have you participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy? | 0.34 | 0.33 | 1.04 | 1.00 | 0.31 | 1.39 | 0.73 | 2.67 |

| Constant | −0.69 | 0.59 | 1.36 | 1.00 | 0.24 | 0.50 | ||

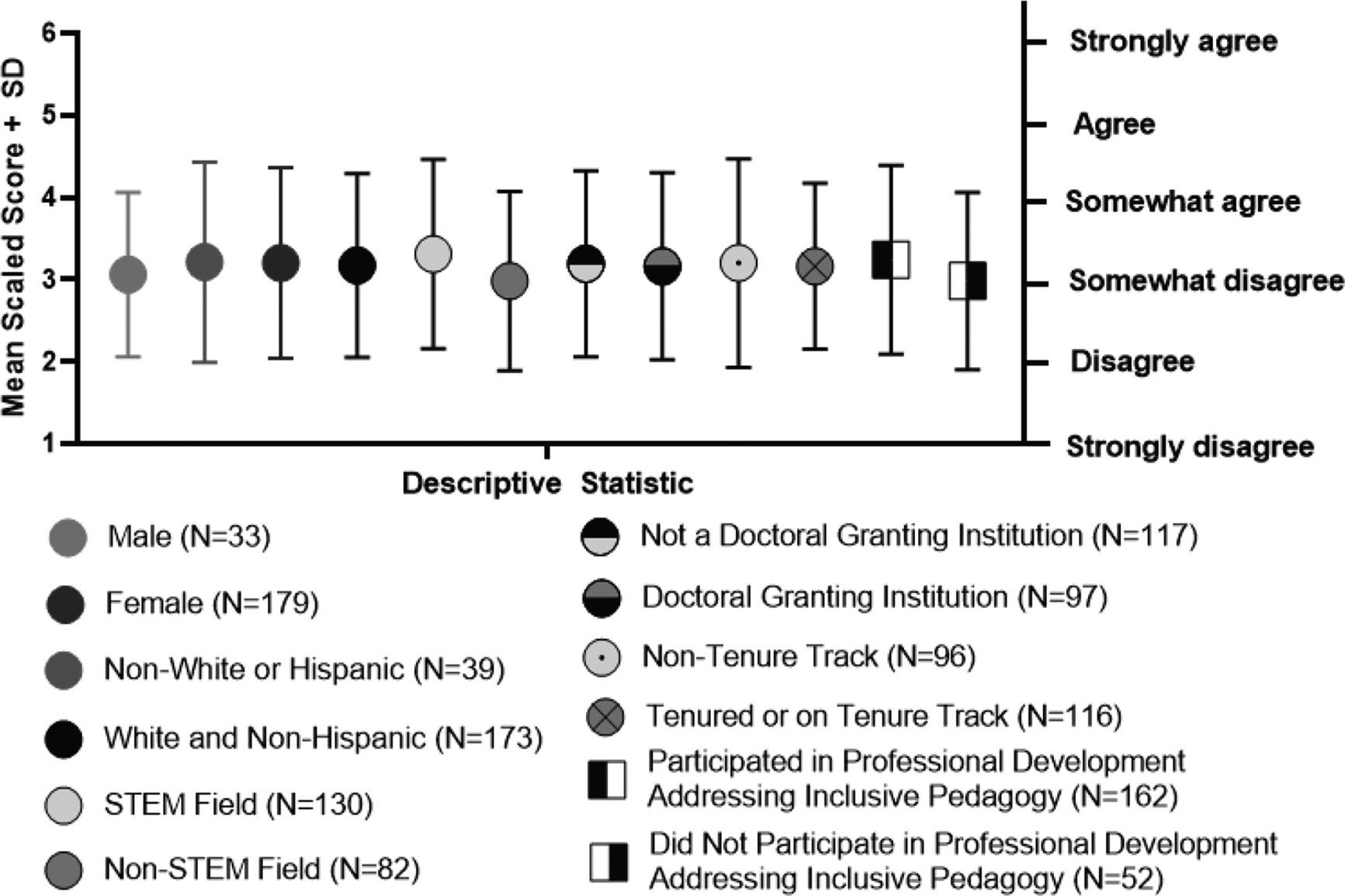

Descriptive statistics for the item “Higher education is making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy” are broken down by demographic characteristics in Figure C8. The overall mean from all respondents was 3.18 (SD = 1.13, n = 214), closest to the somewhat disagree value (3.00) and the lowest overall mean from any of the four levels of query regarding progress in inclusive teaching. The lowest means were found in those that did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy (2.98, SD = 1.08, n = 52) and those in non-STEM fields (2.98, SD = 1.09, n = 82). The highest mean was found in those in STEM fields at 3.31 (SD = 1.15, n =130). The logistic regression model was not statistically significant, χ2(7) = 13.63, p = .06. The model explained 8.4% (Nagelkerke R2) of the variance in agreement and correctly classified 60.4% of cases. Within this model, STEM faculty were 2.17 times more likely than non-STEM faculty to agree with the statement that higher education is making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy (Table 5).

Logistic Regression Coefficients Predicting the Following Item: Higher Education Is Making Sufficient Progress With Regard to Inclusive Pedagogy

| B | S.E. | Wald | df | Sig. | Exp(B) | 95% C.I. for Exp(B) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||||

| Gender | 0.32 | 0.43 | 0.58 | 1.00 | 0.45 | 1.38 | 0.59 | 3.19 |

| White non-Hispanic | 0.20 | 0.39 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 1.22 | 0.57 | 2.59 |

| Discipline STEM | 0.78 | 0.31 | 6.34 | 1.00 | 0.01 | 2.17 | 1.19 | 3.97 |

| Doctoral | −0.19 | 0.31 | 0.40 | 1.00 | 0.53 | 0.83 | 0.45 | 1.50 |

| Tenure or tenure track | 0.16 | 0.31 | 0.27 | 1.00 | 0.60 | 1.17 | 0.64 | 2.14 |

| For how many years have you been teaching? | 0.03 | 0.02 | 3.66 | 1.00 | 0.06 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.00 |

| Have you participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy? | 0.52 | 0.36 | 2.11 | 1.00 | 0.15 | 1.68 | 0.83 | 3.38 |

| Constant | −1.29 | 0.65 | 3.95 | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.28 | ||

Thematic Analysis

In order to carry out a deeper analysis based on previous results, two co-authors conducted a thematic analysis on two open-ended questions in the survey: “Describe the largest barrier to the success of inclusive pedagogy at your institution” (Q1) and “Which types of initiatives have the potential to advance inclusive pedagogy at institutions of higher education?” (Q2). Of these two questions, respondents provided 199 and 176 comments, respectively. The constant comparison method was used by first examining the comments to generate overall themes separately, then coming to an agreement on initial themes (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Next, the raters independently coded the data and uncovered any themes not identified in prior analyses (Q1: Kappa = 0.572, SE = 0.33, 95% CI = 0.50–0.637, strength of agreement = moderate; Q2: Kappa = 0.694, SE = 0.031, 95% CI = 0.632–0.755, strength of agreement = good). Final themes were agreed upon by both authors and comments coded with the revised themes in a final analysis to reach 100% agreement. Several comments consisted of multiple themes, and a number of representative comments from different respondents are included in the article.

Results of Thematic Analyses

Perceived Barriers to Inclusive Teaching Efforts

A thematic analysis of responses to the open-ended question “Describe the largest barrier to the success of inclusive pedagogy at your institution” revealed a variety of obstacles to inclusive teaching efforts, as identified in Appendix D. Barriers were either personal or institutional. Personal barriers included lack of awareness, fear, unwillingness to change, not feeling responsible, and challenges with promoting inclusion in student interactions with one another. Institutional barriers included lack of administrative support, inadequate resources and lack of incentives, lack of diversity and systemic “isms,” and limited opportunities for discussion. Representative comments are also provided from the 199 comments.

Initiatives for Advancing Inclusive Teaching Efforts

When analyzing participants’ answers to the open-ended question “Which types of initiatives have the potential to advance inclusive pedagogy at institutions of higher education?” several themes emerged. Common themes are described in Appendix E. Initiatives reflected institutional commitment and resources (administrative and faculty buy-in, more professional development opportunities addressing inclusive teaching, more resources and incentives, and more opportunities for discussion), departmental supports (general initiatives and better recruitment and retention of minoritized faculty), data-driven approaches (usage of data analytics and conducting assessments that measure impact), and student supports both inside and outside of the classroom.

Discussion and Implications

The goals of this national survey study were to provide insight into what predicts instructor utilization of inclusive teaching approaches across disciplines, obstacles faced, and perceived initiatives that can lead change at institutions of higher education. Knowing which factors impact whether instructors utilize inclusive teaching approaches is of critical concern given the history of exclusion of various groups and the heterogeneity within student populations at colleges and universities. Such information is useful to not only faculty but also administrators and education developers who play a role in providing support to faculty, who can be levers of institutional change.

Key Factors Predicting Utilization of Inclusive Pedagogy

The respondents in the current national study on average reported being knowledgeable about inclusive teaching. Many indicated that they utilized inclusive practices in their courses. Knowledge of inclusive teaching was a key predictor as to whether respondents reported implementing such approaches. While individuals who engaged in professional development activities were also more likely to agree with the statement that they were making enough individual progress with inclusive teaching, reported participation in professional development was not a key predictor of utilization of inclusive teaching approaches.

One reason that participation in professional development may not have been a key predictor of utilization is that respondents may have gained awareness of inclusive teaching approaches through experiences outside of formal workshops or initiatives, such as their own personal experiences in the classroom (as a student or teacher) and more informal conversations with colleagues. However, respondents still expressed value in having professional development experiences addressing inclusive teaching as is evident in the thematic analyses. Furthermore, the difference in utilization scores between those participating in professional development and not doing so is a narrow range for this sample (not statistically significant). These findings corroborate the literature on the critical importance of teaching supports in the implementation of inclusive teaching (Bathgate et al., 2019; Brownell & Tanner, 2012) and highlight a key role for educational development.

In addition to participation in educational development for inclusive teaching, being from a non-STEM discipline was also a key factor for reported implementation of such approaches in this particular sample. STEM courses can face a variety of perceived structural challenges—such as larger class sizes in gateway courses, heavy content where prior knowledge can play a key role in achievement, more challenges or questions around how to integrate diversity and inclusion within the curriculum, and instructors teaching the way they have been taught—that can result in instructors implementing less inclusive approaches (Brownell & Tanner, 2012; Henderson & Dancy, 2007; Herreid & Schiller, 2013; Michael, 2007). The ongoing focus on inclusive teaching in STEM courses in the literature supports this finding, which highlights that the implementation of inclusive teaching poses a distinct perceived and/or actual challenge for instructors within such disciplines (Dewsbury & Brame, 2019; Friedrich et al., 2017; Killpack & Melón, 2016; Penner, 2018; Tanner, 2013).

Respondents also reported more support from their institutions rather than their departments on inclusive teaching efforts. They generally did not perceive that their departments, institutions in general, or higher education were making significant progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy. We hypothesize that the higher departmental and institutional support means found for non-tenure track instructors, while not statistically significant, were reflective of the large number of non-tenure line respondents in this sample being from fields such as education and psychology, where inclusion has a historical emphasis in the discipline. Furthermore, this outcome may also be a result of tenure-track faculty perceiving less support of their teaching efforts due to the heavy emphasis on research at institutions where scholarship production is critical for tenure and promotion. Future investigations are necessary to better understand such findings.

Barriers to Implementation and Change Initiatives

Respondents reported a variety of barriers to the implementation of inclusive teaching at their institutions, such as lack of awareness that inclusion was an issue or lack of professional development; lack of buy-in from their colleagues and administration; fear; not wanting to take on the responsibility; not having enough time or proper resources; lack of incentives; an unwillingness of their colleagues to change their teaching practices; and need for more discussions, assessment and data measures, and a variety of student supports. Change initiatives for promoting inclusive teaching included more and sustained professional development, resources, incentives and rewards, administrative support, student support, equitable hiring and support for diverse faculty, department-level initiatives, data on student diversity and formal assessment plans, and more discussions. Such initiatives are consistent with organizational change theories around leading change, involving having a shared vision around the change and the buy-in of various campus partners (e.g., students, faculty, administrators) to enact policies and procedures and provide resources to further reform efforts (Kezar, 2013). These open-ended responses triangulate the survey findings with reference to perceived barriers to inclusive teaching efforts and initiatives perceived to lead change.

There are some seeming contradictions in the data that could be explored in future work. For example, participating in professional development addressing inclusive teaching was not a statistically significant predictor for the utilization of inclusive teaching practices, but participants also described wanting more professional development to advance inclusive teaching efforts. As mentioned previously, the majority of instructors taking the survey were utilizing inclusive teaching approaches and may have already been invested in using such approaches even without formal professional development yet still recognized the importance and value of professional development that addresses inclusive teaching. Another factor is the degree to which, with regard to quality as well as frequency, the professional development experiences in which the respondents participated led to their adoption of inclusive teaching strategies. Sustained professional development experiences are known to have higher efficacy than single workshops or events (Derting et al., 2016). In other words, participating in one or few inclusive teaching workshops might not be sufficient to lead to adoption of such teaching practices. Furthermore, if the events were not designed to facilitate a change in practice, utilization of inclusive teaching strategies may not be an outcome.

Study Limitations

While this survey appears to be a promising tool for assessing different perceptions of inclusive teaching, more validity evidence ultimately needs to be gathered. The survey was constructed in consultation with a panel of experts to provide some validity evidence related to test content (AERA, 2014) and ensure that the items accurately represented inclusive teaching. Nevertheless, examining how responses correspond to observations of actual implementation of inclusive teaching and correlating responses to other measures of teaching practice or campus climate would provide additional validity evidence in relation to other variables (AERA, 2014) and provide insight into how this survey may be improved. Operationalizing terms like sufficient progress in queries about advancements related to inclusive teaching could ensure more consistency in responses across participants. The survey was developed for the purpose of conducting an exploratory national research study. Adapting the survey for other purposes (e.g., evaluating departmental or campus climate or diagnosing the implementation of inclusive teaching by individual faculty) would require researchers to gather additional validity evidence to support their interpretation of the data.

The survey relies on self-reported data and was distributed via a variety of channels, and the recruited sample therefore may not be representative of the pedagogical practices and opinions of faculty members across higher education. Furthermore, the survey was voluntary; thus, those that were more accepting or knowledgeable of inclusive teaching may have been more eager to complete this survey. The survey may have been taken by multiple individuals at the same institution. Additionally, attrition during the survey may have impacted the results as similar individual characteristics may have impacted participants’ willingness to spend more time answering all the quantitative survey questions and providing in-depth responses to the qualitative survey questions. While the final response allowed us to conduct the analyses presented, a larger number of responses could further clarify relationships found within the data analysis (e.g., implementation by faculty in STEM versus non-STEM fields).

Recommendations for Educational Developers

The outcomes of this study highlight the critical importance of educational development that focuses on inclusive teaching. In particular, for this sample, the findings reveal that knowledge development in inclusive teaching practices was a significant predictor of whether instructors implement such approaches and that participation in professional development focused on inclusive teaching was not. While further study is needed, such outcomes suggest that professional development on inclusive teaching should be meaningfully designed to support adoption.

Institutions could leverage existing programming and relationships when developing additional training related to inclusive teaching. When asked “Which departments or offices (if any) provide professional development for inclusive teaching at your institution?” respondents commonly noted offices such as CTLs and offices of diversity and inclusion. Less regularly mentioned were offices of institutional or education effectiveness, grant-funded programs, and specific departments. By understanding how faculty receive advice and support on their teaching within an institution, educational developers may be able to increase faculty buy-in and adoption. Educational developers may also find it beneficial to emphasize intensive institutes, faculty learning communities, and other forms of more sustained professional development that support the knowledge development of instructors and monitor or assess such learning in place of focusing on holding one-time events that may or may not be as impactful at building foundational understanding of inclusive teaching approaches. An example initiative that provides sustained support on inclusive teaching and other evidence-based practices is the Summer Institutes on Scientific Teaching. These multi-day intensive institutes provide tools and a supportive community to help instructors implement evidence-based teaching approaches. Participants have self-reported using inclusive teaching approaches at higher levels within the two years after the summer institute (Pfund et al., 2009).

Given that being from a non-STEM discipline was a significant predictor of adopting inclusive teaching approaches, a promising change initiative is providing directed professional development activities that support STEM faculty who face actual or perceived challenges with implementation. An initial focus on implementing smaller-scale methods in gateway courses that often emphasize heavy content may be more palatable and impactful in supporting student persistence (Seymour & Hunter, 2019). Passing gateway courses is known to be important for student persistence, and recent work has found that introductory chemistry courses were particularly critical for underrepresented students (Harris et al., 2020). Furthermore, research suggests that physics, computer science, and engineering attract even lower-achieving males, whereas females are less likely to pursue those disciplines unless they have high achievement backgrounds, which can account for gender gaps (Cimpian et al., 2020). Inclusive teaching approaches in such foundational courses may include ensuring accessibility of newly developed course materials, integrating diverse examples, creating an environment that promotes equitable student participation, implementing brief active learning exercises such as think-pair-share, among others. Educational developers, such as professionals who perform work in institutional CTLs, can be strong advocates of equitable and inclusive teaching, demonstrating their values through programming, services, and emphases within consultations. They can play a role in coordinating discussions around equity and inclusion in classroom teaching. Additionally, educational developers can strategically offer services at the department level around inclusive teaching. These may involve specific learning communities geared toward equitable and inclusive teaching for faculty within departments or faculty groups who teach multi-section courses. Educational developers may also provide forums for departments to discuss their largest challenges around equity and inclusion and develop actionable items to address such concerns. Through their initiatives, educational developers can advocate for multicultural frameworks, over those that are colorblind, as evidence suggests that such approaches are associated with the implementation of inclusive teaching (Aragón et al., 2017).

Data-driven approaches uncovered in the thematic analyses may potentially be useful at raising the awareness of instructors in quantitative fields such as STEM disciplines but also have potential in non-STEM disciplines. Such initiatives may include highlighting statistics within the literature and, if available, within the institution that reveal the exclusion of particular student groups or other inequities. Increasing the level of awareness of achievement gaps between student groups is a promising avenue by which to foster change. Such analytics can also be calculated at the departmental, program, or multi-section courses level. Educational developers can work with individual faculty members as well as departments to help measure the impact of implementing inclusive teaching approaches. In general, understanding what really matters to instructors implementing inclusive teaching strategies can support institutional change (Kezar, 2013). The results of this study are also particularly informative for inclusive teaching initiatives addressing inequities revealed through the COVID-19 pandemic and racial unrest occurring across the nation.

Biographies

Tracie Marcella Addy, PhD, MPhil, is the Associate Dean of Teaching and Learning at Lafayette College in Easton, PA. She is responsible for working with instructors across all divisions and ranks at Lafayette to develop and administer programming related to the teacher-scholar model. As the Director of the Center for the Integration of Teaching, Learning, and Scholarship, she develops and delivers programming on teaching and learning. She conducts scholarly work in educational development and more broadly in teaching and learning, including active learning and inclusive teaching. She publishes case studies and is a Course Editor for Professional Development & Career Planning & Science Process Skills of the open-access journal CourseSource.

Philip M. Reeves, PhD, is the Program Evaluation Specialist in the Office of Assessment and Evaluation at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Dr. Reeves is an educational psychologist who has specialized in program evaluation and assessment in the educational environment. His personal research focuses on topics that intersect social, cognitive, and educational psychology, such as self-regulation that helps students and teachers improve their ability to plan, monitor, and evaluate their own learning or teaching. He has presented and published research that examines self-regulatory learning strategies such as help-seeking in classroom, distance, and professional learning environments. He has also collaborated on research projects that have examined teacher training, collaborative teaching, cognitive load, comprehension of multiple documents, executive functioning, metacognition, and test anxiety.

Derek Dube, PhD, is an Associate Professor of Biology and current Chair of the Center for Student Research and Creative Activity at the University of Saint Joseph in West Hartford, CT. Dr. Dube has active research programs examining various aspects of microbiology (specifically virology) and developing and assessing the efficacy of active-learning pedagogies in the sciences. Additionally, he teaches courses in microbiology, genetics, virology, and genomics. Derek earned his doctorate in Microbiology at the University of Virginia studying how Ebola virus enters host cells and completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Michigan studying human endogenous retroviruses prior to joining the faculty at the University of Saint Joseph.

Khadijah A. Mitchell, PhD, is the Peter C. S. d’Aubermont, MD Scholar of Health and Life Sciences and Assistant Professor of Biology at Lafayette College. Her research addresses the causes and consequences of cancer health disparities in underrepresented populations. Specifically, she explores biological and environmental determinants that drive race, sex, and age differences in cancer outcomes. Dr. Mitchell teaches undergraduate STEM courses that intersect with public health, such as Precision Medicine and Molecular Genetics. She integrates research findings from her laboratory into each class and takes ideas generated in the classroom back to her laboratory for further study. Her research, teaching, and service passions lie in both health and education equity. She completed a postdoctoral fellowship at the National Cancer Institute after concurrently earning her PhD in Human Genetics and Molecular Biology from the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and a graduate certificate in Health Disparities and Health Inequalities from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She received an MS in Biology from Duquesne University and a BS in Biology from the University of Pittsburgh.

Acknowledgments

We give special thanks to Dr. Mallory SoRelle for reviewing the Inclusive Teaching Questionnaire.

References

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing. American Educational Research Association.

Aragón, O. R., Dovidio, J. F., & Graham, M. J. (2017). Colorblind and multicultural ideologies are associated with faculty adoption of inclusive teaching practices. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 10(3), 201–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000026https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000026

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2013, June 27). Board statement on diversity, equity, and Inclusive Excellence. https://www.aacu.org/about/statements/2013/diversityhttps://www.aacu.org/about/statements/2013/diversity

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2015). Committing to equity and Inclusive Excellence: A campus guide for self-study and planning. https://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/CommittingtoEquityInclusiveExcellence.pdfhttps://www.aacu.org/sites/default/files/CommittingtoEquityInclusiveExcellence.pdf

Bancroft, S. (2013). Capital, kinship, & white privilege: Social & cultural influences upon the minority doctoral experience in the sciences. Multicultural Education, 20(2), 10–16. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1015027.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1015027.pdf

Bathgate, M. E., Aragón, O. R., Cavanagh, A. J., Frederick, J., & Graham, M. J. (2019). Supports: A key factor in faculty implementation of evidence-based teaching. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-12-0272https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.17-12-0272

Booker, K., & Campbell-Whatley, G. D. (2015). A study of multicultural course change: An analysis of syllabi and classroom dynamics. Journal of Research in Education, 25(1), 20–31. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1097971.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1097971.pdf

Brownell, S. E., & Tanner, K. D. (2012). Barriers to faculty pedagogical change: Lack of training, time, incentives, and … tensions with professional identity? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 11(4), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-09-0163https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.12-09-0163

CAST. (2020). About universal design for learning. https://www.cast.org/impact/university-design-for-learning-udlhttps://www.cast.org/impact/university-design-for-learning-udl

Center for the Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning. (2020). IUSE EHR—inclusive learning and teaching in undergraduate STEM instruction. https://www.cirtl.net/sections/44/pages/iuse-inclusive-teachinghttps://www.cirtl.net/sections/44/pages/iuse-inclusive-teaching

Cilluffo, A., & Cohn, D. (2019, April 11). 6 demographic trends shaping the US and world in 2019. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/11/6-demographic-trends-shaping-the-u-s-and-the-world-in-2019/https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/11/6-demographic-trends-shaping-the-u-s-and-the-world-in-2019/

Cimpian, J. R., Kim, T. H., & McDermott, Z. T. (2020). Understanding persistent gender gaps in STEM. Science, 368(6497), 1317–1319. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba7377https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aba7377

Dee, T., & Penner, E. (2016, January). The causal effects of cultural relevance: Evidence from an ethnic studies curriculum (Working paper 21865). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://www.nber.org/papers/w21865.pdfhttps://www.nber.org/papers/w21865.pdf

Department of Homeland Security. (2016, May). STEM designated degree program list. https://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Document/2016/stem-list.pdfhttps://www.ice.gov/sites/default/files/documents/Document/2016/stem-list.pdf

Derting, T. L., Ebert-May, D., Henkel, T. P., Middlemis Maher, J., Arnold, B., & Passmore, H. A. (2016). Assessing faculty professional development in STEM higher education: Sustainability of outcomes. Science Advances, 2(3), e1501422. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1501422

Dewsbury, B., & Brame, C. J. (2019). Inclusive teaching. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 18(2). https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-01-0021https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-01-0021

Engle, J., & Tinto, V. (2008). Moving beyond access: College success for low-income, first-generation students. Pell Institute for the Study of Opportunity in Higher Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504448.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED504448.pdf

Friedrich, K. A., Sellers, S. L., & Burstyn, J. N. (2017). 9: Thawing the chilly climate: Inclusive teaching resources for science, technology, engineering, and math. To Improve the Academy, 26(1), 133–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2008.tb00505.xhttps://doi.org/10.1002/j.2334-4822.2008.tb00505.x

Fry, R., & Cilluffo, A. (2019, May 22). A rising share of undergraduates are from poor families, especially at less selective colleges. Pew Research Center: Social and Demographic Trends. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/05/22/a-rising-share-of-undergraduates-are-from-poor-families-especially-at-less-selective-collegeshttps://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2019/05/22/a-rising-share-of-undergraduates-are-from-poor-families-especially-at-less-selective-colleges

Gay, G. (2018). Culturally responsive teaching: Theory, research, and practice. Teachers College Press.

Harris, R. B., Mack, M. R., Bryant, J., Theobald, E. J., & Freeman, S. (2020). Reducing achievement gaps in undergraduate general chemistry could lift underrepresented students into a “hyperpersistent zone.” Science Advances, 6(24), eaaz5687. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5687https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaz5687

Henderson, C., & Dancy, M. H. (2007). Barriers to the use of research-based instructional strategies: The influence of both individual and situational characteristics. Physical Review Special Topics—Physical Education Research, 3(2), 020102.

Herreid, C. F., & Schiller, N. A. (2013). Case studies and the flipped classroom. Journal of College Science Teaching, 42(5), 62–66.

Hockings, C. (2010). Inclusive learning and teaching in higher education: A synthesis of research evidence. Higher Education Academy.

Howard Hughes Medical Institute. (n.d.). Inclusive Excellence 1 & 2. https://www.hhmi.org/science-education/programs/inclusive-excellence-1-2https://www.hhmi.org/science-education/programs/inclusive-excellence-1-2

Institute of International Education. (2017). International student enrollment trends, 1948/49–2016/17, Open Doors: Report on International Educational Exchange. Institute of International Education. https://www.iie.org/opendoorshttps://www.iie.org/opendoors

Jung, E., Bauer, C., & Heaps, A. (2017). Higher education faculty perceptions of open textbook adoption. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 18(4), 123–141. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1146205.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1146205.pdf

Kezar, A. (2013). How colleges change: Understanding, leading, and enacting change. Routledge.

Killpack, T. L., & Melón, L. C. (2016). Toward inclusive STEM classrooms: What personal role do faculty play? CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(3), es3. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0020https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.16-01-0020

Ladson-Billings, G. (2014). Culturally relevant pedagogy 2.0: a.k.a. the remix. Harvard Educational Review, 84(1), 74–84.

Li, D., & Koedel, C. (2017). Representation and salary gaps by race-ethnicity and gender at selective public universities. Educational Researcher, 46(7), 343–354. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17726535https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17726535

Lyman, M., Beecher, M. E., Griner, D., Brooks, M., Call, J., & Jackson, A. (2016). What keeps students with disabilities from using accommodations in postsecondary education? A qualitative review. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability, 29(2), 123–140. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1112978.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1112978.pdf

McPherson, E. (2014). Informal learning in science, math, and engineering majors for African American female undergraduates. Global Education Review, 1(4), 96–113. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1055230.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1055230.pdf

Michael, J. (2007). Faculty perceptions about barriers to active learning. College Teaching, 55(2), 42–47.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis (2nd ed., pp. 10–12). Sage.

National Center for College Students with Disabilities. (2020). NCCSD research briefs. http://www.nccsdonline.org/research-briefs.htmlhttp://www.nccsdonline.org/research-briefs.html

Neuendorf, K. A. (2019). Content analysis and thematic analysis. In P. Brough (Ed.), Advanced research methods for applied psychology: Design, analysis and reporting (pp. 211–223). Routledge.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational Researcher, 41(3), 93–97.

Parker, K., & Igielnik, R. (2020). Facing an uncertain future: What we know about gen Z so far. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/essay/on-the-cusp-of-adulthood-and-facing-an-uncertain-future-what-we-know-about-gen-z-so-far/https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/essay/on-the-cusp-of-adulthood-and-facing-an-uncertain-future-what-we-know-about-gen-z-so-far/

Penner, M. R. (2018). Building an inclusive classroom. The Journal of Undergraduate Neuroscience Education (JUNE), 16(3), A268–A272. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6153021/pdf/june-16-268.pdfhttps://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6153021/pdf/june-16-268.pdf

Pfund, C., Miller, S., Brenner, K., Bruns, P., Chang, A., Ebert-May, D., Fagen, A. P., Gentile, J., Gossens, S., Khan, I. M., Labov, J. B., Pribbenow, C. M., Susman, M., Tong, L., Wright, R., Yuan, R. T., Wood, W. B., & Handelsman, J. (2009). Summer institute to improve university science teaching. Science, 324(5926), 470–471. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170015https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1170015

Roberts, J. A., Olcott, A. N., McLean, N. M., Baker, G. S., & Möller, A. (2018). Demonstrating the impact of classroom transformation on the inequality in DFW rates (“D” or “F” grade or withdraw) for first-time freshmen, females, and underrepresented minorities through a decadal study of introductory geology courses. Journal of Geoscience Education, 66(4), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2018.1510235https://doi.org/10.1080/10899995.2018.1510235

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2016). Generation Z goes to college. Jossey-Bass.

Seymour, E., & Hunter, A.-B. (2019). Talking about leaving revisited: Persistence, relocation, and loss in undergraduate STEM education. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25304-2

Skomsvold, P. (2014, October). Web tables: Profile of undergraduate students: 2011–12 (NCES 2015-167). U.S. Department of Education. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015167.pdfhttps://nces.ed.gov/pubs2015/2015167.pdf

Sumner, S. W., Sgoutas-Emch, S., Nunn, L., & Kirkley, E. (2017). Implementing innovative pedagogy and a rainbow curriculum to expand learning on diversity. InSight: A Journal of Scholarly Teaching, 12, 94–119. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1152093.pdfhttps://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1152093.pdf

Tanner, K. D. (2013). Structure matters: Twenty-one teaching strategies to promote student engagement and cultivate classroom equity. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 12(3), 322–331. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-06-0115https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.13-06-0115

Taylor, O., Apprey, C. B., Hill, G., McGrann, L., & Wang, J. (2010). Diversifying the faculty. Peer Review, 12(3). https://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/diversifying-facultyhttps://www.aacu.org/publications-research/periodicals/diversifying-faculty

Tobin, T. J., & Behling, K. T. (2018). Reach everyone, teach everyone: Universal design for learning in higher education. West Virginia University Press.

Twenge, J. M. (2017). iGen: Why today’s super-connected kids are growing up less rebellious, more tolerant, less happy—and completely unprepared for adulthood. Atria.

University of Oregon. (2019). Teaching evaluation framework. https://provost.uoregon.edu/teaching-evaluation-frameworkhttps://provost.uoregon.edu/teaching-evaluation-framework

U.S. Department of Education. (2016, November). Advancing diversity and inclusion in higher education: Key data highlights focusing on race and ethnicity and promising practices. https://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/advancing-diversity-inclusion.pdfhttps://www2.ed.gov/rschstat/research/pubs/advancing-diversity-inclusion.pdf

Appendix A. The Inclusive Teaching Questionnaire (five sections across four pages)

Section I. First, we would like to know about your knowledge of, comfort level and experiences with inclusive teaching.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following:

| Strongly disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Somewhat disagree (3) | Somewhat agree (4) | Agree (5) | Strongly agree (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I can provide a definition of inclusive teaching. | ||||||

| I can describe at least 3 specific inclusive teaching practices. | ||||||

| I can articulate the significance of creating an inclusive classroom environment. | ||||||

| I can utilize inclusive pedagogy in my courses. |

Open-Ended Questions:

Please define what inclusive teaching means to you.

Please list any inclusive teaching strategies that you use in your courses.

Section II. Next, we would like to know about how you may be utilizing inclusive pedagogy in your courses.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following:

| Strongly disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Somewhat disagree (3) | Somewhat agree (4) | Agree (5) | Strongly agree (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I integrate diverse examples into the subject material of my courses. | ||||||

| I implement instructional practices that promote equitable (i.e., unbiased, fair & just) experiences for my diverse learners. | ||||||

| I intentionally engage in equitable interactions with my diverse learners. | ||||||

| I create learning environments that encourage equitable interactions between diverse students. |

Section III. In this section, we are gathering information about your institutional and departmental experiences with professional development for inclusive teaching.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following:

| Strongly disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Somewhat disagree (3) | Somewhat agree (4) | Agree (5) | Strongly agree (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| My institution provides professional development for inclusive teaching. | ||||||

| My institution disseminates online resources to support inclusive teaching efforts. | ||||||

| My institution provides targeted academic support for students from groups historically marginalized. | ||||||

| My department holds informal or formal discussions on inclusive teaching. | ||||||

| My department provides targeted academic support for students from groups historically marginalized. | ||||||

| My department evaluates the efficacy of inclusive teaching efforts. |

Open-Ended Questions:

Have you participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy?

Yes

No

Which departments or offices (if any) provide professional development for inclusive teaching at your institution?

Is facilitating sessions on inclusive teaching part of the normal job responsibilities of the individual(s) providing professional development at your institution?

Yes

No

Unknown

N/A

Describe any inclusive teaching initiatives at your institution. Please be sure to only provide general information that does not identify your institution.

Section IV. In the following section, we would like to know your opinions about progress being made on inclusive pedagogy.

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following:

| Strongly disagree (1) | Disagree (2) | Somewhat disagree (3) | Somewhat agree (4) | Agree (5) | Strongly agree (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy. | ||||||

| My department is making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy. | ||||||

| My institution is making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy. | ||||||

| Higher education is making sufficient progress with regard to inclusive pedagogy. |

Open-Ended Questions:

Which types of initiatives have the potential to advance inclusive pedagogy at institutions of higher education?

Describe the largest barrier to the success of inclusive pedagogy at your institution.

Describe the largest need with regard to inclusive pedagogy at your institution.

Describe any impacts of inclusive pedagogy at your institution.

Section V. In this final section, we are collecting some basic information in order to better understand relationships between inclusive pedagogy and various demographic factors.

What is your title?

Adjunct professor

Visiting professor

Lecturer

Assistant professor (pre-tenure)

Associate professor (pre-tenure)

Associate professor (tenured)

Full professor (tenured)

Other _______________________

Are you a full-time or part-time instructor?

full-time

part-time

For how many years have you been teaching?

At which type of institution are you currently employed? Please see Carnegie Classification System.

Doctoral granting University

Master’s College or University

Baccalaureate College

Associate College

Special Focus Institution

Tribal College

Not classified

Other (describe) _________________________

Do you work at a primarily minority serving institution?

Yes

No

Which has the highest weight at your institution for promotion and tenure review?

Teaching

Research

Service

What is your discipline?

Anthropology

History

Linguistics and Languages

Philosophy

Religion

The Arts

Economics

Geography

Interdisciplinary Studies

Political Science

Psychology

Sociology

Biology

Chemistry

Earth Sciences

Physics

Space Sciences

Computer Sciences

Mathematics

Agricultural

Architecture and Design

Business

Divinity

Education

Engineering and Technology

Environmental Studies and Forestry

Family and Consumer Science

Human Physical Performance and Recreation

Journalism, Media Studies and Communication

Law

Library and Museum Studies

Medicine

Military Sciences

Public Administration

Social Work

Transportation

Other (please indicate)__________

Which types of courses do you teach? (Select all that apply)

Introductory/gateway/foundational

Upper-level/advanced

Graduate level

Professional school

Other (please describe) ______________________

Are you of Hispanic, Latino or Spanish origin?

Yes

No

How do you describe yourself? (Select all that apply)

American Indian or Alaska Native

Asian

Black or African American

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander

White

Other (explain) _____________________

What is your gender?

In which state is your institution?

Alabama (1) … I do not reside in the United States (53)

Appendix B

Respondent Demographics, Geographical Locations, and Number of Years of Teaching Experience

| N | Mean years teaching | SD | Min. | Max. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full-time | 175 | 14.76 | 8.79 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Work at a primarily minority serving institution | 50 | 14.92 | 10.39 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Does not work at a primarily minority serving institution | 162 | 14.02 | 8.28 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Male | 34 | 13.20 | 9.93 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Female | 180 | 14.58 | 8.75 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Non-White or Hispanic | 40 | 14.26 | 10.68 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| White non-Hispanic | 174 | 14.38 | 8.52 | 1.00 | 40.00 |

| STEM | 132 | 14.15 | 8.78 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Non-STEM field | 82 | 14.70 | 9.24 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Not a doctoral granting institution | 117 | 14.80 | 9.29 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Doctoral granting institution | 97 | 13.83 | 8.51 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Non-tenure track | 96 | 13.44 | 8.08 | 1.00 | 31.00 |

| Tenured or on tenure track | 118 | 15.11 | 9.55 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Participated in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy | 162 | 14.46 | 8.53 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Did not participate in professional development addressing inclusive pedagogy | 52 | 14.04 | 10.20 | 2.00 | 42.00 |

| Total | 214 | 14.36 | 8.94 | 1.00 | 42.00 |

| Geographical location of study respondents |  |

||||

Appendix C

Appendix D

Perceived Barriers to Inclusive Teaching Efforts

| Theme | Summary of responses | Representative quotes |

|---|---|---|

| PERSONAL BARRIERS | ||

| Lack of awareness | The lack of awareness of colleagues, particularly, those from majority groups or established faculty, in recognizing that exclusion of students from particular social identities or other attributes occurred at their institution was a significant concern. This was perceived to prevent the utilization of inclusive teaching practices. Respondents also indicated that their colleagues were not aware of how to implement inclusive teaching practices. | Right now my institution does not even realize this is an issue.—Associate professor, tenured, master’s college or university, Education [N]ot knowing what they don’t know—white faculty believing they are inclusive just because they “treat everyone the same.” They are not intellectually against inclusive teaching; they just see all “normal” teaching as being inclusive so there’s no need to invest resources (mental, emotional, or otherwise) into inclusive pedagogies.—Dean and full professor, baccalaureate college, English |

| Fear | Respondents perceived that their colleagues either were scared to offend others or to try out inclusive practices. | Fear of doing it wrong, further offending marginalized groups.—Academic professional, doctoral granting university, Education [I]t might seem intimidating to address some of these issues openly, when instructors might not be part of a particular, or any, diverse group.—Academic professional, doctoral granting university, Biology |

| Unwillingness to change teaching practices | Respondents described how their colleagues, particularly established faculty, did not want to change their teaching approaches for a variety of reasons, such as a general apathy regarding inclusion, lack of buy-in, or association of inclusive teaching with lower standards. | Professors who have been at the institution for decades do not like change. They have the most seniority and sometimes [put] a stop to trying something new.—Assistant professor, pre-tenure, associate’s college, Biology [T]enured faculty are happy to keep things as they are, the hierarchy that protects research over teaching and protects faculty members who fit the traditional mold; valuing teaching gets only lip service but follow the money and it’s not going to those who provide the most service to students—Lecturer, doctoral granting university, Psychology There is some resistance to adapting teaching materials and methods to a changing student population, or a perception that being inclusive is somehow being “soft” on students.—Associate professor, tenured, baccalaureate college, Communication |

| Not feeling responsible | Respondents indicated that a major barrier was that their colleagues did not feel that they were responsible for implementing inclusive pedagogy. | [F]aculty from majority groups who do not believe inclusion is something that they should be responsible for, therefore it should not be in the curriculum.—Faculty developer with adjunct appointment in Human Physical Performance and Recreation, doctoral granting university My university has resisted discussions of minority groups and inclusion, seeing that that is what the office of multicultural inclusion is for, instead of everyone’s responsibility.—Adjunct professor, baccalaureate college, Interdisciplinary Studies Mindsets. Conventional faculty models imply that the social aspect of learning is not the professor’s responsibility.—Assistant professor, doctoral granting university, Biology |

| Challenges in promoting inclusion in student interactions with one another | The significant challenge of helping students be inclusive in their interactions with one another. Respondents expressed challenges in managing biased interactions between students and the lack of awareness of students with regard to inclusion. | It became very clear to me after several semesters that, with all the tools our institution has put in place and still doing so, some students find it difficult than others to be inclusive. In such cases therefore, it is better to change the set of rules for discussions for example, and call on individuals to participate to questions and answers rounds.—Associate teaching professor, doctoral granting university, Biology Systemic injustice. I can’t make my classroom a safe space. I can do everything in my power to make my classroom as safe as possible, but biases in a single student (and the system) can inflict great harm on my students. That terrifies me.—Assistant professor, master’s college or university, Journalism, Media Studies and Communication |

| INSTITUTIONAL BARRIERS | ||

| Lack of administrative support | Not having buy-in from administration that inclusive teaching was valued as well as having inadequate leadership and lacking administrative support. | Lack of support from administration.—Assistant professor, doctoral granting university, Nursing The administration needs to make this a priority.—Visiting professor, baccalaureate college, Psychology |

| Inadequate resources and lack of incentives | Not having enough available professional development on inclusive teaching, limited financial resources such as grants and other funding opportunities to invest in inclusive teaching, and time restrictions given competing priorities. | We have no systematic faculty development programs that address inclusive pedagogy.—Full professor, tenured, baccalaureate college, History Time for faculty to learn about and include anything new in their teaching.—Full professor, tenured, master’s college or university, Communications Money and programming.—Professor of the practice, doctoral granting university, Biology |